Neck Sharpies: July Meets October

One of the questions we pondered after Saturday's game was where were the "July Drive" plays? By that we mean the weird stuff that coaches draw up over the summer and keep in their back pockets to spring on a specific opponent. Michigan certainly had this game circled on the calendar after last year's B.S. We all know Michigan State defines its entire program by hating this one opponent. And what did they bring out, other than the reverse with a QB lead blocking (that Michigan ran against them in 2013)?

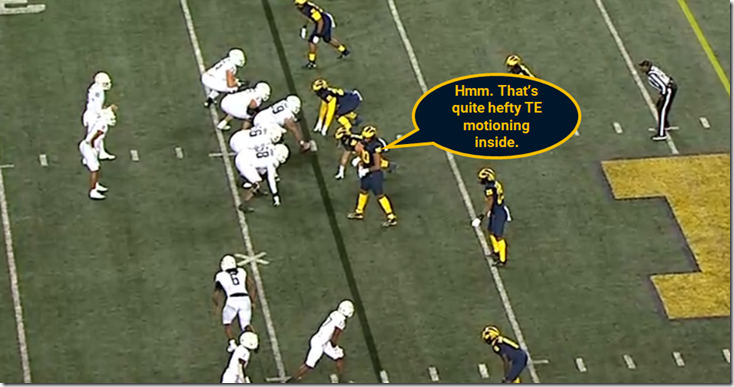

Well, it was there. MSU's scripted opening drive was interrupted by penalties starting on the next snap, and the next was thrown off script by the 4th down stuff. So now State is back in the saddle and ready to do more with this tight end motion game they set up. You'll note in the above play they have the Y motion across the formation then give a stretch zone run look that way before reversing the opposite direction. Their next trick was to have that TE motion across then run a play-action wheel route to him out the back. You don't remember that play because Michael Barrett got on top of the wheel; Thorne was able to scramble for a chunk when Mason Graham went for a sack and Mazi Smith lost contain.

That sets us up for 1st and 10 here at the 37, and we're back on the script. For their next trick, MSU wants to run the opposite direction of the TE's motion. Here's how that goes.

What are they doing? Why didn't it work? The story's more complicated than I can break down in Upon Further Review, so let's get out the sharpies.

[After THE JUMP: It's just a rotation.]

What was MSU trying to do?

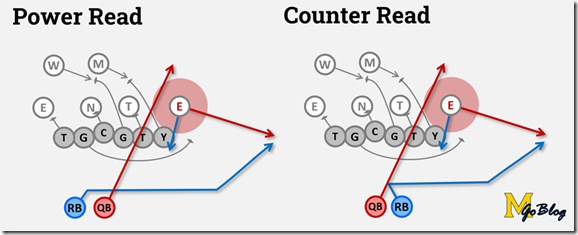

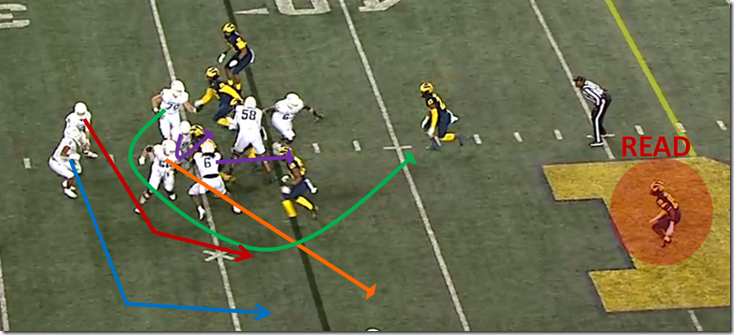

The play here is a version of J.T. Barrett-era OSU's power read (here's the graphic), except with counter action from the backfield instead of a straight veer. Same play, but the RB starts on the other side and the option is a pitch instead of a handoff.

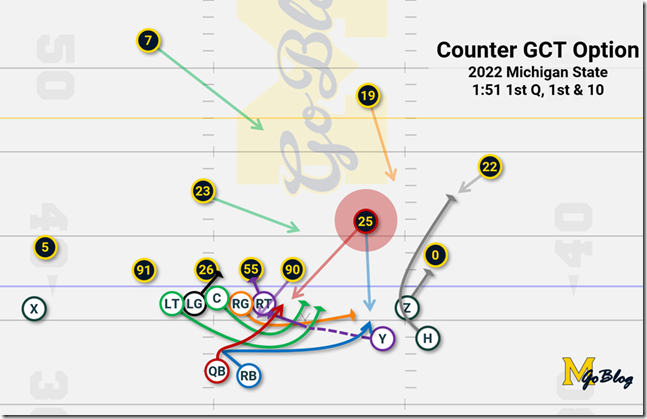

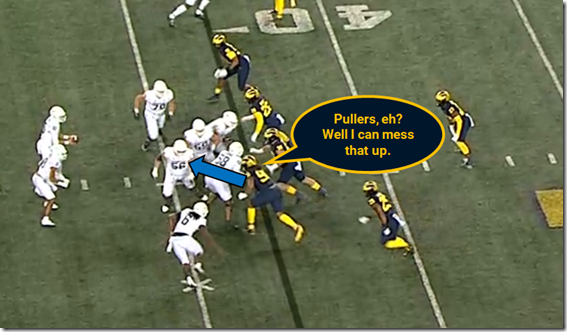

The gist of the blocking is the same as with any power play: block down with the playside and swing around some backside blockers with the first of them kicking out the contain if any exists. A defender on the backside is left unblocked and unread—the expectation is that Michigan's edges are trained to form up and look for a read or a puller not dive inside, so they're gambling here that Taylor Upshaw (#91) will take care of himself. Similarly, the backside DT is to be cut if he goes upfield; if he slants to the backside that guy can be left alone and the LG is free to hunt downfield.

The read is actually on the MLB, Junior Colson (#25). If he comes inside they can turn him inside and pitch it out to the RB. If Colson follows the RB outside as expected, Thorne should be able to pull it down and run inside of that. If Colson tries to split the difference he gets kicked out by one of three pullers.

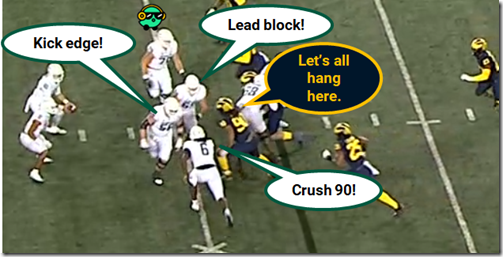

The key here is the defense should not be expecting its frontside edge to be blindsided by the tight end. Remember, the success of gap-blocked plays is all about how big of a gap you can pry open between the downblocks and the kickout.

The expectation here is that Mike Morris (#90), who loves to crash inside when he sees pullers coming across, will get crushed inside by the TE, creating plenty of space outside of him to run an option play. Trying that from a regular formation doesn't work well—Morris just too good of a player and MSU's working with the kind of talent that will voluntarily associate with MSU football. Every inch of fight that Morris can put up is less to spare for the intended gap. The TE from nowhere should gain that rare win vs Morris. Every block thereafter should be Advantage: MSU as you're running three 300+ pound pullers against two smallish linebackers and a tiny safety.

Given the Michigan's tendencies, MSU is expecting to get a big gashy run out of this, most likely to the running back once Colson activates against the pulling action. That's especially true once they see Benny slanting backside and Upshaw staying put, since that's two defenders they don't have to bother blocking, with Colson about to be a third.

It's good math for the offense. Two defenders are unblocked. A frontside defender is getting optioned. The inside of the gap they're attacking is about to be crushed. AND the backside guard is releasing to the second level onto a linebacker (Barrett) who seems interested in playing ball.

All of this plays off the reverse they just saw.

What did Michigan do to it?

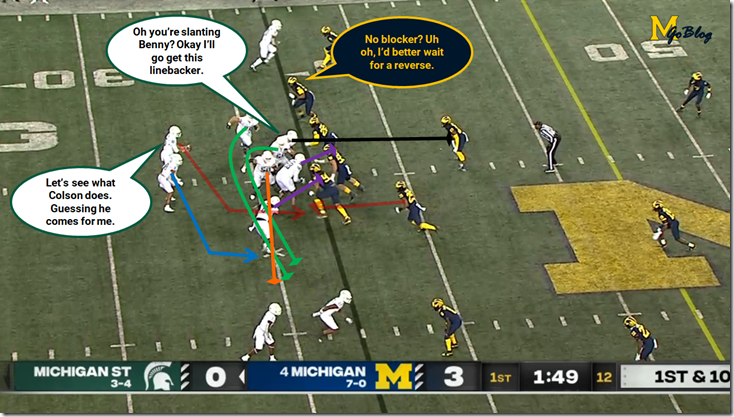

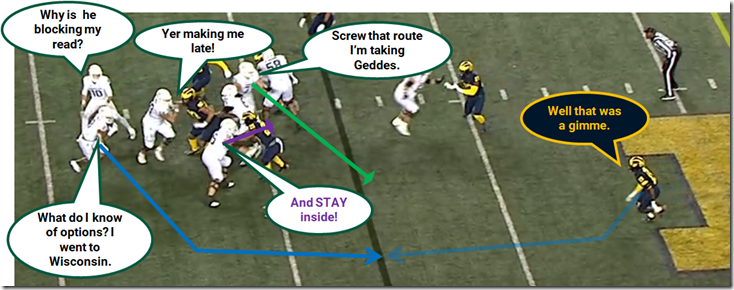

Nothing special. They're in a pretty standard Cover 1 or press 3 rotation with a blitzing MLB. I think Nick Saban would call this "Liz." Rod Moore is rotating down to replace the blitzing Colson, who is replacing the slanting edge of the defensive line.

The slant however throws off the whole Michigan State plan. What Michigan lost by putting an extra DL to the backside they gained in adding a defender to the frontside and moving everybody's responsibilities over. The tight end thinks he's getting that key blockdown on Morris, but Morris is not the inside edge anymore; Colson is.

And now here's where we have to take this play to the next level. Michigan State had a playcall that expected one suite of defenders to block and got a different one. If they were a team that ran a ton of power—like, say, Michigan—they would be extremely grateful for this response. All it takes is an adjustment on the fly.

However that's not really MSU's running game. They're mostly an inside zone/outside zone team with a little bit of power that they run like zone—a style that commentators like to term "student body right" when they see it because it looks like everyone's just hauling ass to one side of the line.

And conversely, this is the kind of thing that Michigan sees all the time. Let's watch Mike Morris as all this unfolds. He notes the TE motion then looks inside; he only cares if the TE comes inside of him.

As they snap it Morris quickly notes that MSU is bringing blockers from the backside. Whatever they're up to he knows they're probably not intending to get involved in a traffic jam in the backfield, so he goes to create just that.

Note where his shoulders and feet are after the snap. He's slanting, angling towards an inside run. As soon as he registers the pullers he changes that. The right foot comes down as a plant. The shoulders square to line. He's missed his opportunity to take out three pullers but he can stop two of them. Meanwhile MSU's blockers aren't changing the plan one iota.

This is our crucial moment. If these blockers had studied at Michigan under Sherrone Moore they might have been prepared for a slant. This is my conjecture here but I think since they're just Airbnb'ing here in Power Town they're not prepared to adjust their directions when a road's closed. The TE is still heading for Morris instead of finding Colson. The second puller doesn't know about turning in edges when a guy ducks under you and still has his whole body turned sideways. The tackle following behind isn't even looking at the cars in front of him; he's scouting downfield for the safety he'll get to block when they all get outside. Thorne is still reading Colson instead of figuring out that Rod Moore is his guy.

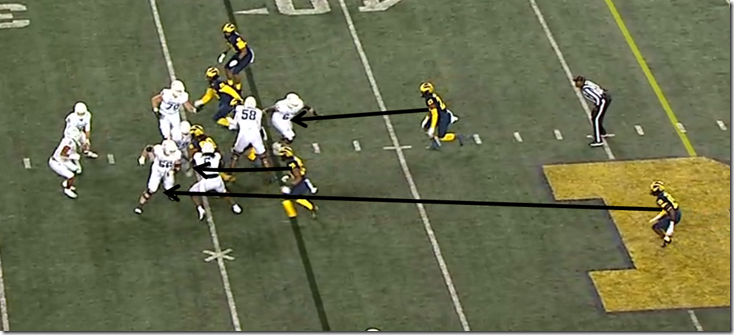

And just like that Michigan has bought back the two defenders they lost on the backside. Morris is effectively occupying three guys: the TE and the two backside pullers. Thorne gives up on his read and pitches it too quickly to the RB so they don't have the read now either. Barrett is easily able to get playside of the releasing backside guard so there's no cutback lane. What we have left are the one lead blocker and a RB for Colson and Moore, who's now about to add himself to the party.

What State could have done, had they been practiced at this stuff, was shift everyone's responsibilities over one spot. The 2nd puller is in tough with Morris and that's probably still going to cost them a chance to swing the tackle around back but it's still possible if he can get Morris turned inside. That's why Morris changed directions to go upfield: so he couldn't get turned in.

Even if they lose that, they could redirect the TE to get Colson, who's taking himself inside, while Thorne looks up Moore, and they're back in business, with a free blocker to take care of one defender and a QB keep option remaining to remove another.

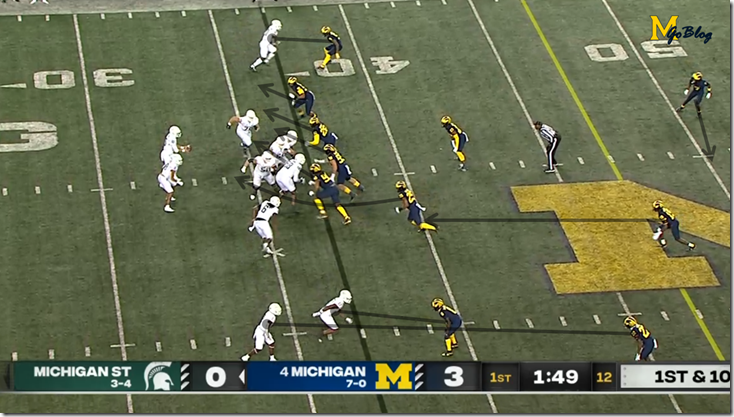

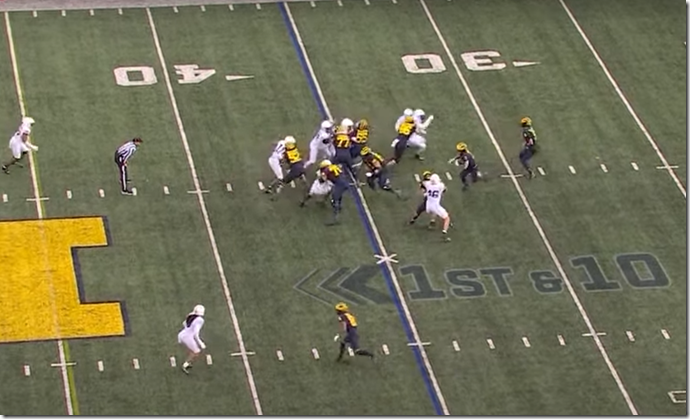

Instead the puller uses himself up to turn in Colson. The backside tackle reroutes downfield. The puller that Morris stopped is four yards in the backfield and at a dead stop—the running back can't afford to wait for him anymore. The tight end is completely useless. Moore has a clear path to meet the RB at the line of scrimmage, whence it gets two yards.

And it's 2nd down and 8.

Things

There was a lot going on here but ultimately we had two simple concepts: a power run versus a slant. When we hand out points Morris gets a pair for being reactive and blowing up the blocking. Minter could have gotten a rock/paper/scissors loss for calling a slant opposite a power run, which is just asking for something like this if it gets blocked up correctly:

However the slant is what ends up throwing off Michigan State's blocking and blows up their very set up, very planned, big surprising July-scripted play. What happened here is Michigan State ran something expecting to catch what Michigan's defense normally does, Michigan's defense did something they don't do normally, and Mike Morris reacted to the weird thing better than MSU's offensive players. The lesson here is for all of us who think of football play-calling as coordinators trying to gamble on the right plays. That makes some difference, but how your players are prepared for October is a much more important aspect of coaching than what you can draw up in July.

November 1st, 2022 at 12:53 PM ^

These Neck Sharpies really highlight the importance of coaching within the play. Players (especially OL/DL) who understand how their bread and butter plays work and how to adjust post-snap when things get weird can turn RPS losses on their heads.

November 1st, 2022 at 1:01 PM ^

Is there a reason we think this is a "July drive" and not just a few wrinkles/tricks they had time to add with an extra week to game plan?

Is there really evidence it's something that's carried over from Dantonio to Tucker?

November 1st, 2022 at 1:52 PM ^

It's just a figure of speech. "July Drive" is a scripted drive that was saved especially for a certain opponent. It would be extraordinary indeed if MSU wasn't practicing stuff from that drive specifically for Michigan all year.

November 1st, 2022 at 1:10 PM ^

Great stuff Seth! I'm no football analyst, but it sure looked like little brother trying to run power in a backyard game.

November 1st, 2022 at 1:33 PM ^

Goddamnit I love this shit. Mainline it into my veins!

November 1st, 2022 at 1:34 PM ^

Seth, can you give a crash course on "frontside, backside, playside," etc? I'm always a bit confused by these terms.

November 1st, 2022 at 1:51 PM ^

It's all here: Upon Further Review: The Glossary | mgoblog

Quickly though, these all refer to ways to tell which side of the play we're discussing. The descriptions change based on timing, as we shift from formations to action. It also matters which team we're discussing, since the offense generally knows which side they're attacking (playside) while the defense is thinking in terms of direction of play (frontside).

WHICH WAY IS THE PLAY GOING?

- Frontside: The side the direction of play is going.

- Backside: The side away from the direction of play.

- Playside: The side the play is actually going.

The reason "Playside" may not be "Frontside" is because of plays like counters that are designed to attack the backside. Arc, Split Zone, Belly: these are all backside attacks.

WHICH SIDE OF THE ALIGNMENT?

- Strongside: The side with more players on it, or if equal the side with the most likely angle of attack (eg the side with the tight end, opposite the side with the RB)

- Weakside: The side with fewer players on it.

WHICH SIDE OF THE FIELD?

Applies unless they're set up in the middle of the field (horizontally)

- Field: The wide side, e.g. if the offense is on the left hash the right side is the field side.

- Boundary: The short side.

November 1st, 2022 at 2:12 PM ^

I read your stuff. I listen to your stuff on podcasts. You are one smart guy, football-wise and beyond. You’d be fun to have a beer with.

November 1st, 2022 at 4:17 PM ^

Having been to some of the Chicago kick-off events, both with powerpoints and HTTV, can confirm. Is fun to have a beer with.

November 1st, 2022 at 4:23 PM ^

I'm guessing he was at Matt D's restaurant with free beer and refundable parking last weekend. Mgo usually does a few pre game things a year they advertise.

November 1st, 2022 at 6:38 PM ^

yes but we were drinking old fashioneds. Seriously though, of my many happy places at the end of a picnic table drinking with good people outside--"holding court" as I like to call it--is right up there. It's why I loved Casa Dominick's days.

November 1st, 2022 at 2:26 PM ^

I know this isn't your nomenclature, but it seems way more confusing than it should be. Like for the Power Read diagram:

Frontside Right

Backside Left

Playside Right

But for the Counter read diagram:

Frontside Left

Backside Right

Playside Right

Do I have that right?

November 1st, 2022 at 2:54 PM ^

Seth, if I start using this terminology and sleep at a Holiday Inn Express can I call myself a football analyst? Thanks for the great work.

November 1st, 2022 at 6:36 PM ^

Yeah. Nobody ever made a rule for what constitutes a football analyst. If you analyze any football whatsoever that's what you are. There's no bar to entry, as I'm living proof.

November 1st, 2022 at 2:07 PM ^

“Hefty” TE? Not blorpy?

November 1st, 2022 at 2:50 PM ^

thicc boi

November 1st, 2022 at 3:32 PM ^

C H O N K or chonky

In extreme cases, "OH LAWD, HE COMIN'".....

November 1st, 2022 at 2:09 PM ^

Superb as always - great explanation and great graphics!

November 1st, 2022 at 2:24 PM ^

Good stuff as always. Who’s got it better than MGOBLOG readers?!

November 1st, 2022 at 4:56 PM ^

well played sir

November 2nd, 2022 at 10:41 AM ^

I was going to say Nobody, but the answer is Harbaugh, the master mind behind weird stuff. :)

November 1st, 2022 at 2:30 PM ^

Amazing to see where all the action is - 2 yards BEHIND the line of scrimmage. Looking at M offense in comparison, action is at or forward of the line. What a difference!

November 1st, 2022 at 2:58 PM ^

Thanks for the excellent breakdown. Love the "play to the whistle" effort by Morris and Colson. Moore very shrewdly kept contain to let them join the party once they shed their blockers. Great team tackle.

November 1st, 2022 at 3:33 PM ^

The lesson here is for all of us who think of football play-calling as coordinators trying to gamble on the right plays. That makes some difference, but how your players are prepared for October is a much more important aspect of coaching than what you can draw up in July.

There was some bye-week debate about whether Harbaugh had innovated enough to create a new offense. Whether he has or hasn't, I think the in-play processing, chemistry and creativity of both the offense and defense has been pretty excellent these last couple of years - and honestly they've looked smart on some of these concepts since the Shea Patterson days. Just how quickly Morris processes (1) what's going on, (2) what he can do to stop it, and (3) position his feet/shoulders/body - all of that on an unscripted but probably somewhat choreographed response - well, that's why they say "talent beats scheme" i guess. Great breakdown.

November 1st, 2022 at 5:05 PM ^

I remember thinking when I first started reading Mgoblog and Michigan offense would not gel because 10 players would do the right thing and one guy would make a mistake, that Harbaugh might be trying to instill an offense that would work well in the NFL but was too much to ask of guy a year or two removed from high school. I didn't understand why he was trying to teach such a complicated system. This is a perfect example of why. The difference between MSU running this play and M running this play is night and day. It took longer to get here than I thought it would, but the payoff is amazing to watch.

November 2nd, 2022 at 10:48 AM ^

The "ten man football" crap back in the Hoke days rankled because it was a load of bull and I knew it was a load of bull. The player making a "mistake" was invariably someone faced with a situation they weren't trained to handle, because Borges coached plays that assumed defenses were static.

There are two ways to teach: rote and concept. Rote is repping a piano piece purely with muscle memory, tech support by runbook. . . monkey see, monkey do. Arrow on the play diagram says go here and bop that guy. Easy to learn. Efficient, when everything goes according to plan.

But what about when they don't? What if that guy you're supposed to bop isn't there? What if you're accompanying a singer and they ask for a key change (transposition)? What if there is no runbook for the problem the customer's reporting? Now you have to think, and that's when you realize with horror that there's nothing between your ears that'll help you. You make a "mistake" and your coach/boss blames you for their failure to prepare you properly.

Harbaugh might be trying to instill an offense that would work well in the NFL but was too much to ask of guy a year or two removed from high school.

It is too much to ask, at least at first, so you're on point. There are exceptions (Mason Graham?), but most players don't receive deep conceptual teaching in HS, and it takes MUCH longer. That's the downside. A call center rep can learn a runbook in five minutes. Actual troubleshooting took me about three years. You can pick up "Maple Leaf Rag" in a few weeks with dogged practice, but pro musicians (the kind that actually know their shit) are expected to sight read, transpose, improvise. . . to do any of that, you need to master the instrument itself. That takes years, practicing for hours every day, during which you'll be playing relatively few pieces because the foundation needed is truly massive.

Football, same thing. The worst coach can teach the dumbest player "go here and bop guy", but you get the "ten man football" stuff because opponents aren't going to obligingly line up exactly how you want. Running something like power or inside zone against all the various fronts, slants, stunts, exchanges and other crappe defenses do to confuse you. . . mastering a single play takes many hours of practicing against all those different looks.

(FWIW, concept isn't the be-all either. Trick plays tend to be rote -- they're surprise attacks you generally don't run twice, so execution doesn't need to be flawless. But if you want to run a certain play ten times a game -- >100 times a season! -- you need to grok what it does.)

November 1st, 2022 at 3:34 PM ^

Neck Sharpies.....(part of) The MGoBlog Difference.

I think I know football and then I read this, and I realize I really don't. It takes special football players to execute on the fly like this, and we have them.

November 1st, 2022 at 4:21 PM ^

Hey that one MSU OL has done some great scouting on the route I use to get home.

November 1st, 2022 at 6:28 PM ^

A groisen dank, Seth! Outstanding explanations.

👍👍

November 1st, 2022 at 8:14 PM ^

Nice analysis

November 1st, 2022 at 8:25 PM ^

Excellent stuff Seth. Appreciate the content!

November 2nd, 2022 at 12:43 AM ^

Morris is just one tough ass ball player.

And he has proven to be a very intelligent one. He gets better and better.

This team plays smart football. You see it in the coaching and you see it in the adjustments.

No more getting beat on fades in solo coverage on 3rd and 25.

November 2nd, 2022 at 7:57 AM ^

Morris is looking more and more like a guy who could play in the NFL for a long time. May not have sexy drafting stats, but is big enough and can just play.

Reminds of Wormley in a way (who is in his sixth pro year, and still going).

November 2nd, 2022 at 11:25 AM ^

Really informative insight, Seth. Thank you!

Still more than a little worried about how Colson, Barrett, and Moore-Paige-Moten hold up against the wrinkles coming their way at the Horseshoe in a few weeks, but stuff like this helps me understand how Michigan's DL is serving as a pleasantly surprising difference-maker. The combination of Morris, Smith, Jenkins, and Harrell-Okie might just be greater than the sum of the parts.

November 3rd, 2022 at 2:02 AM ^

nice stick by #19 S Rod Moore on the RB. its no gain until RG #58 pushes the pile forward.

Comments