Neck Sharpies: More Depth Than Front

Poke any general or military historian with what's the biggest blowout battle in history and they'll either say Cannae or have a reason why not. In August 216 BCE Hannibal of Carthage finally got the Romans to engage him. Hannibal weakened his middle and concentrated on winning at the edges, and the Romans walked right into the trap, creating a bulge in the middle that turned into a Carthaginian envelopment. Thus compressed, the superior Roman numbers (86.4k to 50k) and heft (80k heavy infantry vs 32k heavy and 8k light infantry) were more hindrance than help, further reducing the space they needed to operate. It was an annihilation.

One of the most frustrating parts of Michigan's offense this year to me was they were constantly unprepared for the #1 thing that opponent defenses do. The first half of the Rutgers game was more of the same. Some of the endgame was too. But for most of the second half, the Wolverines were suddenly running plays that suggested they had at least read about Cannae, and had an idea how to get out of one.

[After THE JUMP: Marian reforms needed.]

How Rutgers Plays Defense

What I mean by how a team plays defense is really how they cover up for their weaknesses. Much of the meta game in football takes place in figuring out how your opponent is cheating to cover up a weakness, then doing things that take advantage of it. The primary weakness for Rutgers is one that'll be familiar to you: they don't have enough nose tackles. The starter is Julius Turner, who's listed at 6'0"/265. His backup is 6'5"/265. The other DT spot is a 6'4"/274 guy who was 250 last year backing up Michael Dwumfour, whom you will remember as a first step Michigan never could manage to turn into a football player. What they do have plenty of is outside linebacker types.

Schiano's answer is the Stunt 43 I touched on in Foe Film last week. Now we can break it down a bit better.

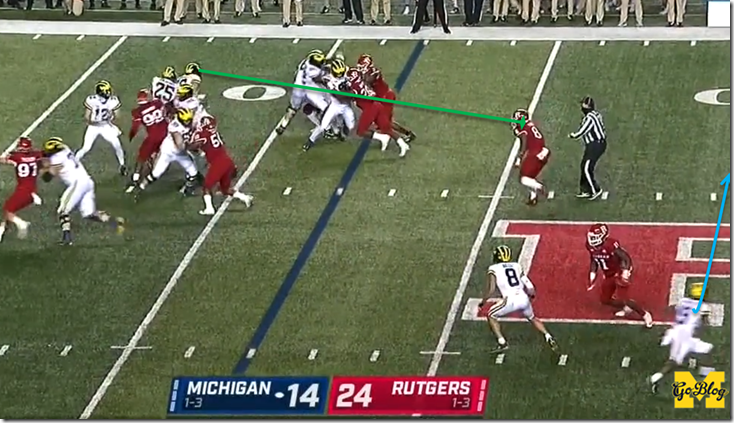

The "stunt" part is what they're doing with the Jack (we'll discuss why in a minute). The "43" refers to a 4-3 front. The Stunt 43 is about jamming up the middle using the path of the nose tackle, removing one of the interior gaps because it's just a pile of humanity in there, and keeping your linebackers clean to bounce outside and clean up. Here it is in action, on Michigan's second play from scrimmage in the 2nd half:

It comes off looking like a mass of humanity in the middle, free tacklers on the edges, and a rushing Rutger in play. When we slow it down, you can see there's more to it. What's really going on is a tactical retreat in the middle in order to compress the attackers, then envelop them, countering their superior numbers by compressing the space they can operate in.

STAGE ONE: COMPRESS THE INSIDE

The first thing you'll notice is they set up with the Nose on an angle towards the center's head. This nerf's the offense's ability to take advantage of their superior size directly off the snap. Just like the little nose guards in Bo Schembechler's slant-based "angle" defense, this little guy is supposed to get under the center's pads from that angle as quickly as possible, then do everything he can to gum up the works.

Even if he gets pushed downfield it's going to gum up the interior. The center can't get a release because he's got this dude in his chest. The guard can't get a release because he's got this dude's butt in his way. And the dude is so low they can't get rid of him. Let this block go on long enough and he'll just go to the ground, keeping all of your blockers trapped there.

The next thing is the activity of the 3-tech (Dwumfour) and the 5-tech. Where the nose's first step is angled, the 5T and 3T (can I call them the techs?*) are going upfield. Everything here relies on burst, getting a foot in the backfield and their heads into their initial gaps. Getting into those gaps is crucial to restricting space in the middle. They're setting an edge of sorts, jamming weights to either side of the mess the nose created. Again, the point is to delay the offense's ability to release anybody downfield. You can see it especially with Dwumfour's attack:

He's outside of Zinter and attacking the shoulder, cutting off Steuber and Zinter from releasing downfield. The entire line is now bottled up at the line of scrimmage.

* [Historically these were both called "tackles" and the guy in the middle was a "guard." I wish we hadn't changed things because it would make it so much easier to talk about all the modern 3-4s, 4-3 unders, 404 Tites, 3-3-5s, Buck 4-3s, and other odd fronts defenses use today without specifying which non-nose is an end and which is a DT.]

STAGE TWO:

You can also see the WLB (#3) activating against Filiaga up top. It looks like a blitz but a middle linebacker is going to be firing at anything that resembles run action. Behind Dwumfour the JACK (#26) is stunting inside. They're about to come into play as a second wave of defenders bottling up any interior gaps and keeping the last linebacker clean.

These two have hybrid jobs. The WLB would have to back into coverage if the quarterback's head pops up to look for openings. The Jack would convert his little stunt into a full one, crossing the formation and attacking the first gap that gives him a clean shot. That's why they're watching the backfield so hard. There's a read going on here. I'll use an example from later in the game to show you how important that interior edge is to them. Watch WLB #3 (Olakunlie Fatukasi) fly up on this play when he sees Dwumfour get double-teamed.

Back to our original play. It's a run, and therefore they're responsible for keeping the guards from getting free. Their arrival is the signal to the Techs that they can now stunt outside. They disengage with the guards and engage the tackles. Crossing the tackle's face creates an edge, but if the tackles stick to them, that means the linebacker is free to pop outside instead. In this case we can see both: Dwumfour and the Jack stunted, and SDE #97 took on a play-long double so WLB #3 could hop outside.

Technically there's an extra gap in here but there's no way Haskins can get into it. In fact #50 managed to use a push-rip move on Carpenter, who's now on the ground blocking nobody. Count the hats inside however and even without Carpenter (329), Michigan still Filiaga (345), Zinter (334), Steuber (339), and Barnhart (301) inside versus a 265-pound nose, a 234-pound WLB, and a 248-pound DE/OLB. The problem is they have no room to do anything with that size advantage because they're getting Hannibal'd.

STAGE THREE

The last piece of this defense is the cleanup man, MLB #8. All of this activity up front was about keeping him clean so he can read the running back and go wherever he does.

How Michigan Attacked It

Longtime readers know my Neck Sharpies Rule of Three [ways to defeat any football concept].

- Execute: Play assignment football. Every man does his duty, though duties may not be even.

- Moves and Countermoves: We guessed you would do this, and did something unsound to catch you at it.

- Dominate: A great play/valiant effort by our hero turned the tide.

1. EXECUTE

Once you've established that you can run, you put the defense at a disadvantage. As I noted in FFFF, Rutgers system puts that backside linebacker in a run-pass bind by design. This is the weakness of the Stunt 43. That same guy they're trying keep clean—the guy whose reaction will determine how many yards the running back gets—is also one of their most important intermediate pass defenders. The safeties are high, and playing quarters, and one of the ILBs has to fire on anything run-like since he's a big part of the fit in exterior gaps. Often Rutgers will have their backside LB set up seven or eight yards off the line of scrimmage—nearly out of the box—to make sure he's in position to cover slants and crossers, figuring he can make up the ground after the snap. After the above the WLB stopped taking extra yards. He's the ILB on the top:

This was a very well drawn-up play. The WR action on the top forces the safety to stay away from the seam, so this is all up to whether the SAM (Singleton) can provide a chip on the TE and the MLB (Tyshon Fogg) can cover Eubanks. Singleton isn't thinking about the TE release because he suspects they're trying to edge him, and Fogg is regretting the two yards. This play also requires McNamara to read the guy, and to make a good pass over the DE trying to bat it, and for Eubanks to come down with it.

2. COUNTERMOVES

Brian pointed out in the game column yesterday that the reason Michigan was able to run that RPO to the TE was because they'd finally established they could run the ball. The example he gave was actually a specific countermove to what Rutgers does. It's a "Trap" play, which means they let a DT into the backfield only to whack that guy with a block from the backside.

They should have done this more, but once that SAM has seen it you figure he's going to react whenever the tight end goes for a trap block.

3. DOMINATE

The least interesting answer to "Why did this work" is "Because Player X did something great" and when you're breaking down Rutgers it's the answer you probably least want to hear, since that's less replicable against real football teams.

The fits and starts of the running game on Saturday had roots in #1 and #2: Michigan has young offensive linemen who often screw up their assignments—especially when they're difficult ones. And for whatever reason—probably the same one—Michigan doesn't install a lot of things specifically for their opponents. Sometimes they do (see the MSU game) but they're bad at it.

These factors are interactive; if you screw up an execution you could still get back to the positive with a tactical win and a great individual effort. How many UFR breakdowns read like:

"Silly freshman(-1) biffs a thing, but nobody's home because a defender was wiped out by the play call (RPS+) and then Studs McSmurfyface(+2) does a thing.

There's going to be a few of those this week, and I caught one at the top of this drive.

You may have noted the play I used to demonstrate the design of the Stunt 43 defense was a 2nd and 1. This was because of a nine-yard Hassan Haskins run—Michigan's first play from scrimmage of the second half—that immediately preceded it. Despite Michigan losing a lot of their one-on-one blocks, Haskins had the space to break a tackle and pick up a chunk.

The reason for that space twofold: Michigan swung their blocking in two directions to create more space along the front, and was Gattis had an RPO read that kept the cleanup man from activating in time to cover all that space.

Here's that play:

It's a Pin & Pull—the offense's base running play back the last time they had one—with an RPO on the backside ILB.

This is how the Roman Army responded to the Cannae disaster. Rather than treating the line like a phalanx—one big wall working together—they went to a system of sub-units that were capable of more complex and surprising maneuvers. One of these "manipoles" wouldn't just stay inside until they were useless; they could pull flanking maneuvers, reinforce other areas, and puncture holes in the enemy front, causing a rout.

Likewise there's no reason to leave the big guards inside just to have them squeezed between the Techs. Pin & Pull (and its cousin, Counter Trey) is Michigan's most natural response to the Rutgers defensive strategy. It's a return to status-quo: mono-e-mono: man to man: just you, me, and my guards. Oh and one of those guards—Chuck, his name's Chuck—is kicking out your cornerback. Meanwhile the Jack and MLB coming inside-out provides an opportunity to get them stuck inside with blockdowns. Gattis deployed a senior tight end and a tackle in a tight end's shirt to this purpose.

To this Gattis has added a read on the backside linebacker, putting that guy in a run-pass bind. In this case the WLB has a lead blocker (Zinter) in front of him, as well as the Sainristil route behind. As I noted above, the WLB in the Rutgers defense often ends up caught between his run and pass jobs. Slapping an RPO read on him isn't taking him out of his lane (unless you run the RB out of the backfield and use the QB as your runner), but it is holding him back until the handoff's made. He plays this one well enough, stepping up when he sees that Dwumfour is going to make a pass difficult.

One absolute fact is that Michigan's offensive line has gone dramatically downhill in that time. A year ago our starting right guard was Michael Onwenu, who was on track last I looked to be the NFL Rookie of the Year according to the level of analysts who believe blocking is part of football. Thanks to injuries and graduations and whatnot it's now true freshman Zak Zinter, who's going to true freshman this play hard. Michigan also lost both of its blockdowns on this play; both tight ends—Honigford (#85) and Eubanks (#82)—are planted on their respective bottoms by the Jack and MLB, Eubanks comically. Also Dwumfour, the 3-Tech, has that big burst and got a step upfield of Barnhart.

That could have ruined the play. It is, in fact, the whole point of Rutgers using this strategy. Dwumfour's get-off means he can be in the backfield before Zinter can get around him; indeed he bumped Zinter off his route and into Haskins, and might have been in position for a thundersack on a pass read. In classical tactical terms, the way to stop the enemy from pulling material out of the phalanx is to drive hard and fast through any gap in the phalanx and cut off the flanking maneuver.

Zinter getting bumped puts him in a bad way but neither does he seem to remember what his job is, as he continues outside to push on the back of Filiaga's block on a cornerback instead of turning inside to look for the backside linebacker.

There's something else to notice here, however. Lookit all that space. Against your normal fronts pin and pull is trying to crack the outside and push in the inside to attack outside. The defense's flanking maneuver has put so much material outside, and used up Dwumfour to fly upfield as fast as possible, so their forces are now split into two groups, with just one unit in any position to close down the space in between. And he's been held by dangers to the South.

Hassan Haskins is going to win some UFR points for turning Fogg into mist here, but I hope we save one for the playcall that created all that space despite some atrocious blocking.

Michigan also adjusted to Dwumfour later on. If you can pull your eyes away from the play-irrelevant, CONSPIRACY(!)-level holding by Schoonmaker on the outside (thanks, line judge

It works because BEN MASON actually makes a block, but it's still dodgy because Rutgers is shooting the Jack into the backfield. Also Haskins reverses field like a boss after getting caught behind the Jack.

The offense has a long way to go yet, but there are some things they can take away other than "escaped Rutgers." They did know how the Rutgers defense worked, put their guys in positions to succeed, and prepared multiple looks.

November 24th, 2020 at 12:11 PM ^

a Wham block baby!

I've been obsessed ever since Iowa 2016

November 24th, 2020 at 11:32 PM ^

You should remember them from Jim Schwartz' time with the Lions. His base D alignment was a Wide 9, which invites LOTS of wham blocks.

November 24th, 2020 at 12:26 PM ^

Well, someone needs to give Brown a lesson on that battle... because his players overpursue, and don't keep assignment.... that late TD was due to blown assignment by Barrett... no excuse for it... and any competent OC sees this and will design plays with their mindless overpursuit.

November 24th, 2020 at 12:58 PM ^

Thing about Cannae is that it was also a one-off. I don't mean Hannibal being a flash in the pan; I mean that guy was a mad genius who never did the same thing twice.

Less heralded than Cannae but equally trolly was his victory at Lake Trasimene; he set up his army on the far side of a hill overlooking a lake, at night (bear in mind this was during the Iron Age). When the Romans passed by in the morning Hannibal launched the ambush, starting from high ground and pinning the Romans against the lake. At one point the cavalry was mopping up by wading through the water and chopping off any heads that surfaced.

It's important to study how he beat you, but that only gets you to one step behind. After Cannae, the Romans basically avoided him as much as possible, cutting him off and pestering him with skirmishes but otherwise letting him rampage through Italy until he ran out of steam.

If, in the study the the great field commanders of history (Hannibal, Subutai, Napoleon), there was any sort of theme applicable to football, it's that they all understood how to create advantages by maneuver, even if most of them hadn't read The Art of War by Sun Tzu:

The spot where we intend to fight must not be made known; for then the enemy will have to prepare against a possible attack at several different points; and his forces being thus distributed in many directions, the numbers we shall have to face at any given point will be proportionately few.

For should the enemy strengthen his van, he will weaken his rear; should he strengthen his rear, he will weaken his van; should he strengthen his left, he will weaken his right; should he strengthen his right, he will weaken his left. If he sends reinforcements everywhere, he will everywhere be weak.

Numerical weakness comes from having to prepare against possible attacks; numerical strength, from compelling our adversary to make these preparations against us.

November 24th, 2020 at 1:44 PM ^

Mgoblog: Come for the existential angst, stay for the military history.

November 24th, 2020 at 2:37 PM ^

I think what we can take away from all this is that there's nothing inherently faulty with our coaching, the problem is the ungentlemanly manner in which other teams deploy underhanded machinations like tempo and multipronged attacks. The Michigan difference is having the integrity to valiantly proclaim your intentions and honoring your word, other teams could learn something from our stalwart respect and honor of football.

November 24th, 2020 at 4:15 PM ^

Another thing about Hannibal that is relevant to football is the way he develop and deployed a tactical asset that was not easily replicated, i.e. his Carthaginian and Numidian cavalry, which played a decisive role at both the Trebbia and Cannae. It was largely because he did not have the Numidian heavy cavalry (Scipio had them) that he lost at Zama. Likewise, when JH was at Stanford he had those great o-lines and that running scheme that couldn't ever really be stopped. But what has he developed along these lines at Michigan? We were hoping that Drevno would replicate the Stanford/49er O-line, and I suppose Harbaugh has been working alot on the pin-and-pull scheme of plays (let's not forget how he dominated ND last year with this). But no distinctive offensive asset (and thus identity) has yet been forged by Harbaugh at Michigan. One reason for our mediocrity on that side of the ball.

Now, Don Brown came with a defensive scheme that had distinct tactical assets. The problem is that they have been essentially defeated by the OSU approach that everyone now replicates. So our defense is now like the French heavy cavalry at Agincourt, which is, you know, really bad.

November 24th, 2020 at 12:26 PM ^

I would argue Austerlitz for two reasons: 1) It's Napoleon, who is the GOAT; 2) He destroyed not one but two armies, and he didn't do it on the off day when a goofball was in command of the Roman legions (not to take anything away from the great Hannibal.)

November 24th, 2020 at 12:29 PM ^

mono-e-mono: man to man: just you, me, and my guards

Wondering if this had anything to do with anything

https://mgoblog.com/comment/243985760#comment-243985760

November 24th, 2020 at 2:15 PM ^

Need the tackles, too.

November 24th, 2020 at 2:23 PM ^

mono-e-mono (mano a mano) actually means hand to hand, not man to man

November 24th, 2020 at 10:19 PM ^

Surprised no one here has gotten it yet. It's a reference to Robin Hood: Men in Tights.

November 25th, 2020 at 12:56 AM ^

THANK YOU

November 25th, 2020 at 1:42 AM ^

Mono e mono = monkey and monkey

November 25th, 2020 at 6:37 AM ^

Did you check the comment I linked to?

November 25th, 2020 at 10:30 PM ^

I believe I did but now I can't remember. Maybe it only took me to the beginning of the post where that comment was. But anyway I see it now :)

November 24th, 2020 at 12:42 PM ^

Interesting that you chose Cannae for the analogy. If we're going for a battle in which a defender launches an unconventional push on the middle in a desperate attempt to encircle an advancing foe, I would have chosen the (similarly-shaped) Battle of the Bulge.

November 24th, 2020 at 12:47 PM ^

And it was the Fabian strategy of avoiding pitched battles that triumphed over Hannibal. Marian's reforms probably would not have helped as much as consolidation of imperium into one general, rather than having two consuls who split command on alternating days. Legend has it that the two consuls disagreed about whether to give battle at Cannae, so one consul simply waited until it was his turn to lead before walking into the now-infamous disaster.

November 24th, 2020 at 1:13 PM ^

So basically you are saying we need to find our own Scipio Africanus to command our troops? Widen the splits, give the elephants some openings?

November 24th, 2020 at 1:22 PM ^

Zama was won because Scipio neutralized Hannibal's recruiting advantage. Despite all the time he spent in Italy, Hannibal never again scored the sort of program-defining victory that would allow him to swell his ranks with local croots. Scipio brought the battle to Carthage, forcing them to recall Hannibal to defend his home. At Zama, the elephants were a non-issue; it was the combined Roman and allied Numidian cavalry that ultimately turned the tide. So we need to get someone who can go into enemy territory and convince their croots to fight with us, rather than against us.

November 24th, 2020 at 12:45 PM ^

Great Sharpies, Seth.

Haskins displayed great feet and vision during the Rutgers game. He had some great cutbacks, even though those cutback lanes were sometimes created by a combination of luck, bad blocking, and Rutgers chosen defensive run strategy.

A side note: how in the holy hell did we lose to MSU?

November 24th, 2020 at 1:12 PM ^

Haskins had 8 carries for 56 yards against MSU. When a guy is averaging 7 YPC, I think you give him more carries. Meanwhile, Corum, Charbonnet and Evans combined for 28 yards on 13 carries. What the hell are the coaches looking at in practice?

November 24th, 2020 at 12:51 PM ^

I guess this puts to rest the "Harbaugh has taken over the offense," meme. He would never think to have the backside RPO. That is pure Gattis. Good man.

November 24th, 2020 at 1:55 PM ^

Ehh, I feel like that trap play is all Jim though. I think it is both of them, not just one should take the blame / glory, it's a collaborative effort that just hasn't produced results.

November 24th, 2020 at 6:22 PM ^

Also, I don't understand the assertion that establishing the running game allowed them to run the RPOs. The RPO for a nine yard gain on the first play of the second half was before they "established" the running game. It was that option that froze the LB long enough to put Haskins in space with him.

And it was McCarthy being in the game and having the coaches trust that allowed them to call those plays. The playcalling changed as soon as he came in. And it opened everything up. So again, it appears that Milton was the reason they weren't calling any of these option plays, which sort of absolves the playcalling the past three games but then begs the question of why Milton was even playing if they didn't trust him with most of the playbook.

November 24th, 2020 at 12:55 PM ^

Seth,

I hope that you do not mind that I ask a question not about the above very complete explanation.

Often this year the team runs a play where Milton hands off to the RB while he is facing due left parallel to the LOS. It appears to be a read option, but he never keeps the ball. My question is "Why does he spin counterclockwise and slowly without the ball move in the opposite direction of the play?" He obviously has not read anything that is happening behind him (right side). No player on the defense ever pays him any attention.

November 25th, 2020 at 12:58 AM ^

It's not a read it's a rollout.

November 24th, 2020 at 12:58 PM ^

Funny thing about the Battle of Cannae is that the Roman's got tired of following the strategy of Quintus Fabius Maximus Verrucosus who had decided to not fight direct battles against Hannibal but pecked away at him instead and disrupted his supply lines. He was replaced by Gaius Terentius Varro who lost at Cannae. Afterwards the Romans went back to what's become known over the years as a Fabian Strategy and ultimately drove Hannibal out of Italy and defeated him. In United States history most notably used by George Washington in the Revolutionary War

November 24th, 2020 at 1:05 PM ^

Yay?

"Please, sir, I want some more."

November 24th, 2020 at 1:19 PM ^

Sorry Seth I did not see any pass options in these plays. Maybe an illusion of RPO, but these are power run plays out of the spread. Well designed with bluff pass but every WR in the frame was in blocking mode not pass-catching position. These are concepts to get a run game going.

The distinct change in 2nd half play calling looked a lot like PSU and beyond last year. Power run concepts and play-action pass. Even that first play above is not a true RPO, as the correct "read" would have been hand off given the depth of the MLB. That play was designed pass all the way with a late breaking TE on a frozen MLB. Very well designed play-action pass with good execution.

November 24th, 2020 at 1:43 PM ^

Why do you keep pursuing this point? I responded to you in a previous thread with a clear example of McNamara throwing on a called RPO (his first pass in the game actually). Link here for your viewing again: https://youtu.be/9cMe3xUf-40?t=257.

The example Seth gave of the 9-yard run by Haskins is very clearly an RPO. If that WLB plays any closer to the LOS or over-commits to the backfield, Sainristil is open right behind him in a soft area between the safeties playing back deep. That route-combo (sit and slant is how I refer to it) is also something Gattis has installed here; Shea Patterson ran it very well against MSU and Indiana last year.

And no, the touchdown pass to Eubanks is pretty evidently an RPO. Cade's eyes are reading the LB again, and while you're correct that the LB starts with good depth, that Cade keeps the ball in Charbonnet's gut for the right amount of time gets the LB to creep up. Eubanks' un-disrupted release allows for him to easily get behind the play-side backer and thus allow for a solid pitch and catch on the lob.

There is no "illusion of RPOs", they were just simply RPOs.

And, as Seth explained at the top of this post, these RPOs work BECAUSE of Rutgers' chosen defensive style of play. Their weakness is that their MLB or WLB will be in a "run/pass bind" as Seth called it.

November 24th, 2020 at 1:28 PM ^

Excellent neck sharpies once again Seth. Does the board know who typically on a staff looks for these intricacies? I have never been around teams/coaching staffs at this level. Is it the offensive and defensive analysts? I know Gattis supposedly does game plans but are the coordinators doing all the film work or is that non-field coaching staff?

November 25th, 2020 at 1:04 AM ^

They have a staff of people who watch film and categorize it then the coaches request different things. They will also get summary reports. Then the coaches watch all the direct film and order up film of things that worked against the same concept.

November 24th, 2020 at 1:39 PM ^

Cannae? pfft. In 331 BC Alexander was outnumbered 2 to 1 (at least) and still won

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Gaugamela

November 24th, 2020 at 2:37 PM ^

Kind of funny, back in my college days I wrote a final paper for a class that compared the two battles trying to determine which was more impressive. I took a stance for Cannae in the paper, but they are both decisive victories.

November 24th, 2020 at 2:39 PM ^

Scipio Africanus was the superior military figure...after all, he sent Hannibal back to Carthage.

November 24th, 2020 at 4:03 PM ^

Alexander had an overwhelming tactical advantage in the Companion Cavalry, against which the Persians had no hope. Plus he had Philip's updated Macedonian phalanx. This massive advantage somewhat downgrades his tactical achievements. Still, he'd make a super head coach.

November 25th, 2020 at 1:53 AM ^

You have to hand it to Alexander for basically inventing zone blocking.

November 24th, 2020 at 2:35 PM ^

Me, casually scrolling down the page, skipping over Neck Sharpies: Wait, is that the battle of Cannae?

Also me: Comes to the comments to read the various takes on the battle and skips over the football part

November 24th, 2020 at 3:05 PM ^

The offense has a long way to go yet, but there are some things they can take away other than "escaped Rutgers." They did know how the Rutgers defense worked, put their guys in positions to succeed, and prepared multiple looks.

This doesn't really instill confidence. Ask me how I felt after the PSU loss last year and I was of the opinion that the offense finally got over the hump of understanding the entire playbook and was willing to call anything. They weren't going to bash Alabama or OSU into the earth, but you knew they weren't going to come out and run into piles of dudes 15 times for 2 YPC. At some point they were going to scheme something open or start calling stuff that had a better chance of working.

This year, they ran straight into brick walls against MSU and Indiana 25 times with absolutely no self-awareness. MSU was going to play tight on the outside with a Safety in the parking lot and have it's LBs fire down to stop the run. They did that. Michigan... didn't really do anything to counter it. Indiana sent corner blitzes and Michigan... didn't counter it. By the looks of it they came into those games with, let's say 30 plays and ran 8 of them over and over again to no avail. Randomly jettisoning RPOs and screens for weeks on end.

We've seen the offense is not a true "speed in space" 11 man attack. They don't have actual QB reads on these shotgun runs. Patterson was a disappointment, no doubt, but it's clear now that it wasn't he was incapable of making a read (at least not entirely). They just don't actually run a RO/RPO offense most of the time. We've seen them run RPO concepts, but either sporadically or defenses have found ways to play the pass while sending enough guys to clog the run that a change up has to be employed.

The offense, at this point in time, should not be a "build" into something from a play calling perspective. It makes absolutely 0 sense to see what we have thus far this year and square it with last year post 1st half PSU. Lack of experience cannot explain running straight ahead into piles of dudes. Even if you don't have the confidence in the younger guys to do the difficult things that the offense might ask of them, they go in spurts of not even attempting the simple things like a bubble or flare screen. Then they don't take a single downfield shot for almost an entire game. Then they eject the QB run out of the playbook entirely. I have absolutely no explanation for that mind you, but at this point in Harbaugh, Warinner, and even Gattis' career, randomly curtailing the playbook for weeks on end makes absolutely no sense.

McDaniels and Shanahan might have bad games or run into good defenses on occasion that stop them, but you know that they at least have a full playbook at their disposal. If they get stuffed at the LOS 10 times they stop running it and try outside runs or quick passes to get away from their issues. At no point does it appear that they just have a 2 page playbook and they're trying to piece together 4 yards at a time. That's not to say they are well versed in every play call and can run 1000 things. It's to say they can adjust on the fly and run stuff that can work if the other defense goes zone heavy or fires their safeties at the LOS. The current offense sure seems the opposite of that far too often. We're going to run IZ or a pin and pull whether it works or not because we don't have something else to replace it. We saw what the offense could look like last year. It was legitimately good. Top 20 S&P good. The current play calling with Onwenu, Bredeson, Runyan, and Collins wouldn't go anywhere either.

November 24th, 2020 at 5:20 PM ^

I've now learned a moderate amount about offensive football strategies and quite a lot about famous military strategists.

November 24th, 2020 at 5:31 PM ^

Seth, this just adds to the Fullcast's stereotype of Michigan fans as military history nerds.

November 24th, 2020 at 6:31 PM ^

Hannibal had a smaller army that was incredibly diverse; a Swiss army knife of different types of units that had years of experience fighting together and could be deployed any way needed to counter an opponents strengths, led by a generational genius who could maneuver them in ways that we still talk about today.

The Roman army at Cannae was an inexperienced behemoth led by glory-seeking fools who thought their name was worth something on the field. All it could do was go SMASH and everyone knew it.

Much like collapse of the German army at Stalingrad the Roman army did not protect their flanks adequately, instead choosing to deploy their extra men in the middle and left the below-average Roman cavalry and both Consuls to face Carthaginian cavalry that was among the best in the world.

Almost immediately the Roman wings were routed and chased from the field, leaving a lumbering and leaderless mass of humanity to be sucked into the trap, surrounded and destroyed.

November 25th, 2020 at 1:10 PM ^

So we need Scipio Africanus to save our offense? Good God, that's a reach.

November 26th, 2020 at 4:30 AM ^

Mason's block in that last play is confusingly good. How's he move that guy so easily? The defender stopped moving his feet and Mason didn't, I guess, but the movement he gets there is really something.

Comments