Neck Sharpies: Up the Gut

Shot through the heart, cuz your LB’s too late. [Barron]

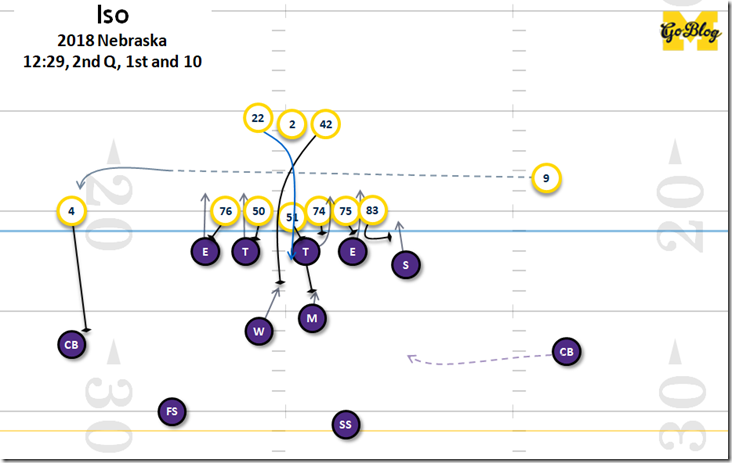

In a departure from Michigan’s first few games this season, Down G didn’t work against Northwestern, however a sort of similar A-Gap Isolation play was gashing them on the regular. This was not surprising given how Northwestern aligns its front, a thing I noted in the Foe Film last week.

Base Set: It's a 4-3 even, the same that Michigan State bases its defense out of. Even when they shifted to an under look they kept the wide splits between the DTs:

This is a thing you see Match Quarters defenses do when they like their middle linebacker a lot. The uncovered center can be dangerous since there's nobody to chip him if he releases on a linebacker. If you trust your MIKE to beat that block consistently you can get away with this bubble, making up for it with more strength in the B and C gaps.

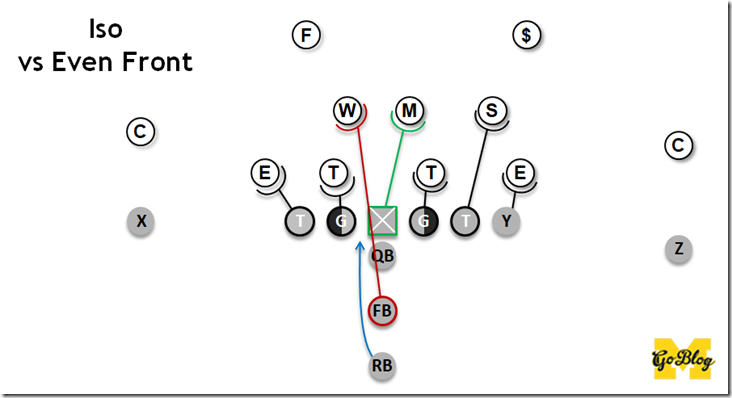

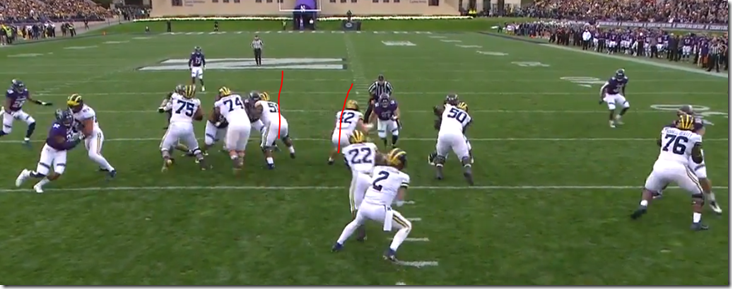

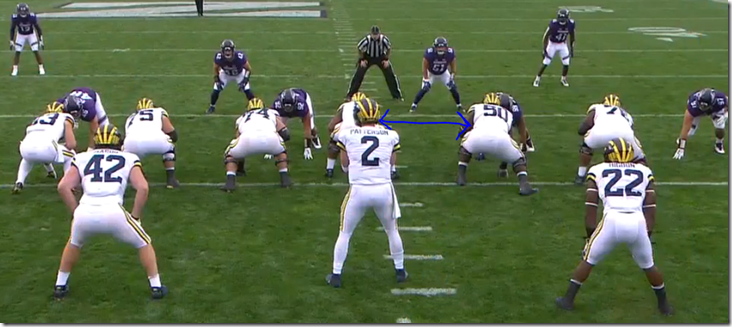

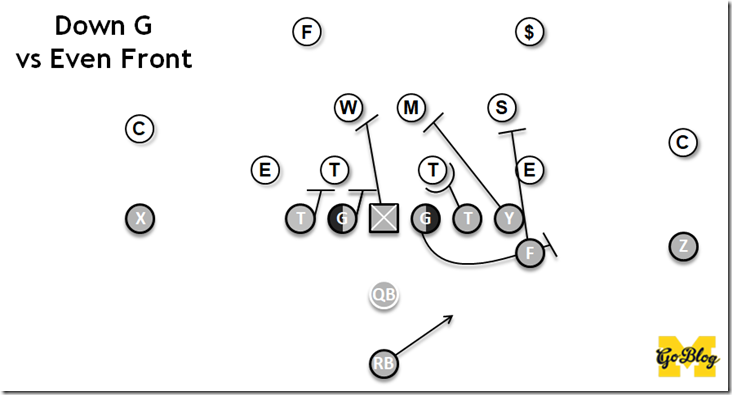

And here’s how Harbaugh attacked it:

Before digging into this let's go over some actual football terminology. That way I can use the jargon later to explain why Michigan's curveball play worked so well against previous opponents, but was not expected to work against Northwestern, and why this cut fastball was devastatingly effective.

GAPS, TECHS AND SHADING

Ever since offenses learned to pass and run outside, their opponents have had to array their defenses with some points stronger that others. How you set the strong points of your front and react to the weaker points will establish your defensive identity.

This starts with where you line up the defensive linemen. They are your fortresses. Linemen are difficult to move, and the linebackers usually will line up at least partially behind those lineman to create an impediment for releasing OL to get a shot at them.

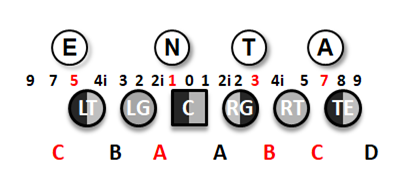

Here’s a typical (4-3 over) alignment:

- Techniques are those little numbers I put between the defensive and offensive lines. They are instructions for the defensive linemen as to how they’re going to line up. When we talk about a “3-tech” for example, that’s a guy who lines up off of a guard’s shoulder. There is no single established numbering system across football so I used what I’m familiar with above. Note the numbers in red correspond to where the defensive linemen are set up.

- Shading is an instruction to the offensive linemen, often represented in graphics by coloring in all or part of a lineman to show who’s got a defensive player lined up on him. This comes into play with line calls, zone running, or any play that changes up the blocking depending on how the defense aligns.

- Gaps are represented with letters, and are used by offenses and defenses alike to refer to gap assignments and attack plans. The letters in red denote gaps where a defensive lineman is lined up. An offensive player without a defensive player shaded on him is considered "Uncovered."

- Under/Over can refer to the front as a whole or a player. "Under" means weakside, "Over" means strongside (the side with the tight end)

So in this example alignment you could say the nose is aligned in a 1-tech shaded under the center and attacking the A gap.

Now see if you can find the softest spot in that front above. If you said backside B gap you get a lollipop. Not only is nobody lined up in that gap but the nose is on the opposite side of the next gap, leaving the left guard uncovered. To avoid that, a lot of 4-3 teams will put their nose in a “2i” technique, or over the guard’s inside shoulder, especially when the offense is in a spread formation and there are only two LBs back there to help.

The gaps that aren’t covered are (usually) the linebackers’ problem. Linebacker gaps are more pliable because they have other responsibilities besides that gap, such as passing, matching pullers, and dodging blocks from offensive players not committed to the linemen.

No team stays in the same front with the same linemen attacking the same gaps every play unless they want to be mercilessly attacked by plays that go at their weak points. They’ll shift their fronts, and also slant guys into different gaps than they started in, and blitz their other players to stuff up more gaps. But they also try to spend as much time as possible in the front that best uses their talent.

Now, see if you can spot the soft spot in Northwestern’s front:

You get a lollipop.

[After the JUMP: Why this works so well, and Down G wouldn’t]

-------------------------------------

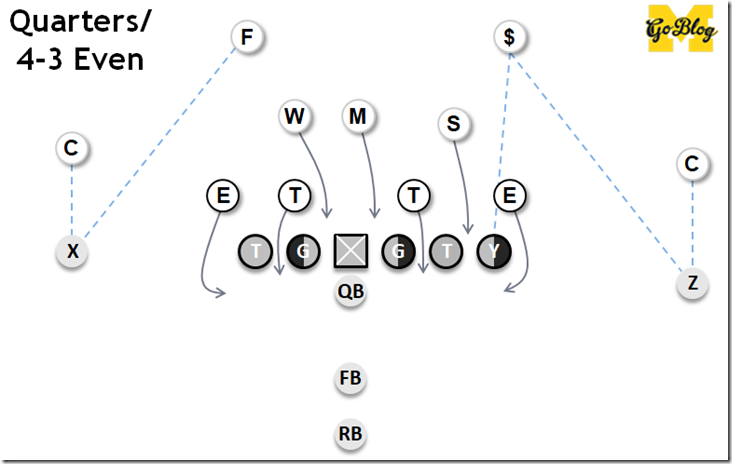

NORTHWESTERN’S 4-3 EVEN AND WHY THEY RUN IT

Like Michigan State, Northwestern is a base 4-3 even team that uses a lot of Quarters coverage, which means their safeties are heavily involved in the run game. There are some obvious differences in how their defensive backs play (that’s beyond the scope of this article) but the fronts are very similar. Northwestern prefers to have their DTs take the B gaps, giving their middle linebackers the A gaps.

This has some benefits. The linebackers are squeezed into the middle of passing lanes, forcing throws that are further outside with worse angles and more time for the defense to rally. Those prime B gaps that Inside Zone and Power teams love to attack are both covered with great big DTs. Also the DEs can spread out more, giving the defense a prime pass rusher from both sides (this is why The Gaz is more Winovich—or more precisely, Shilique Calhoun—than Gary).

Also since teams don’t often even bother to send receivers into the meat of your linebacker level, you can get away with blitzing both of them right up the A Gaps they’re covering—the dreaded “Double A-Gaps Blitz.”

The downside is there are no linemen in the middle of the defense. You’re leaving the center totally “uncovered”, with linebackers responsible for the gaps to either side of him. You can only run this consistently if your middle linebackers—especially the MIKE—can both cover and defeat blocks. You’re giving the center a free shot at these guys. You’re also gambling that your DTs can fight back to restrict those gaps, staying in the B gaps but pushing their blockers inside to clog up the A gaps with bodies.

Ruiz has a clear path to either LB

This describes Northwestern pretty well. Their MLB, Paddy Fisher, is a neck-rolled throwback who loves to bang into blockers and was PFF’s best run stuffer last year. Their WLB, Blake Gallagher, is a sophomore breakout player who’s adept at staying back and knifing past attempted blockers. None of their DTs are nose-like but they’re all disruptive, strong 3-techs

The 4-3 Even plays to their strengths, making life harder on the inside linebackers who can handle it. That buys some DTs in the way of your favorite running lanes, and more strength to the edges. In an age when nobody remembers how to use a downhill fullback anymore this is an excellent strategy.

UNTIL YOU MEET BEN MASON…AT SPEED

This is an “Iso” play, short for “Isolation.” It looks like Inside Zone, and is blocked like inside zone, right up until the fullback screams into a gap with an unblocked linebacker. It is the MANBALL-iest of plays: find a guy across from you and kick his ass. In most versions the Iso requires you double-team/combo an interior lineman. But when the defense does that for you by alignment, all you have to do is keep them where they’re standing.

The lane is behind your fullback, right up their stinkin’ gut.

Iso is the First Play, literally the first play in Yost’s playbook. Power and Zone and all the other running plays exist because football defenses adapted to stop Iso before the forward pass was allowed. But it’s not a game-breaker, and because of that Iso regularly falls out of favor outside of short situations. The history of football defense, in fact, is that of teams borrowing an Iso defender to help somewhere else, shortly thereafter followed by someone who brings back some version of the T-formation and pops them in the mouth.

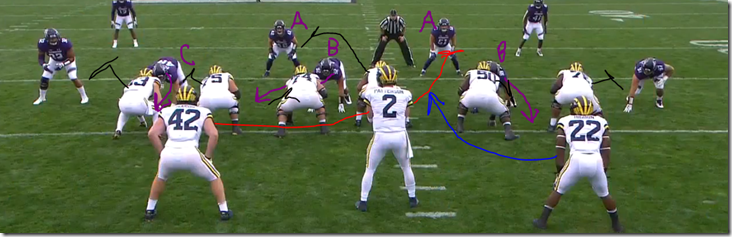

On this play Northwestern indeed aligned in “1-tech” (center’s shoulder) in an Under front, but slanted that guy back to the B gap.

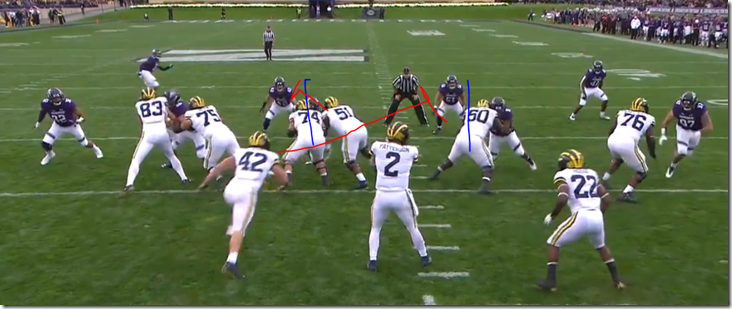

Thus, the slant effectively converted the “Under” they showed back to an “Even”—the front Northwestern likes best, and also the front that Michigan designed this play to attack.

With the tackles in the B gaps, all Runyan and Onwenu have to do is seal those guys and not get shoved back into the hole. Easy enough. The slant by the NT does Bredeson’s job for him, and gives Ruiz a free run on Paddy, who’s watching a quarterback take a shotgun snap and can’t fire until he sees either a handoff or Ruiz move past the line of scrimmage. As long as Bredeson and Onwenu—Michigan’s Big Big Boys—hold those linemen where they are there’s a big lane forming.

The “Isolation” part then comes into play as the fullback lead, isolated on the linebacker covering the backside A gap, plunges head-first into that guy. This is the play right here: however long it takes the WLB (#51, Blake Gallagher, to the right of the hash mark) to react to a fullback charging at him, the more space the running back will have to run by him. He doesn’t take his first, noncommittal step toward the line of scrimmage until the ball’s in Higdon’s basket and Mason is up to full speed.

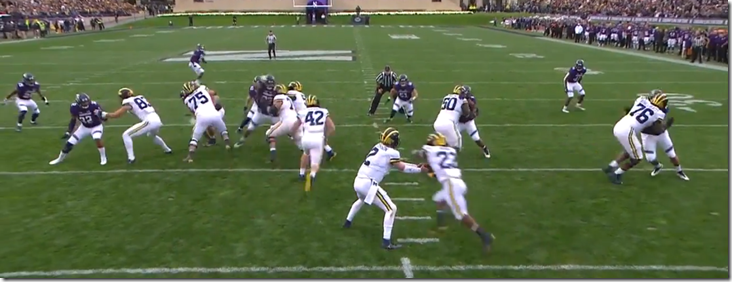

And once he realizes what’s happening, Mason has effectively inserted an extra gap in the line, and Gallagher is on the wrong side of it.

Paddy is in his gap but he’s a linebacker and Ruiz is large. Gallagher can maybe try to knife behind Mason, or at best rock Mason back to squeeze the gap shut. Also note there’s a cutback lane forming if Onwenu’s DT fights back to Gallagher’s gap, but there’s also a Quarters safety stepped down and in position to keep that down.

And then Mason connects. This is what you get from a weaponized Harbaugh fullback: not only is Gallagher sealed, he’s not even on the hash anymore. As Mason forces contact, mass and acceleration are both in Michigan's favor, and Gallagher is treated to a lesson in Newtonian physics.

Michigan did two more things this play to increase the space to run through. (1) They jet-motioned DPJ to the side they were running it, creating a threat that revealed Northwestern’s Quarters coverage, pulled the safety wider, and maybe got in the WLB’s head a bit, though the WLB isn’t responsible for DPJ unless he slants inside. (2) They added spacing between the center and the right guard. Look how wide the gap they’re attacking is:

Offenses leave subtle clues to their intentions all the time, but at this level most of them are probably missed.

WHAT IF THE DEFENSE DOESN’T GO IN THEIR GAPS?

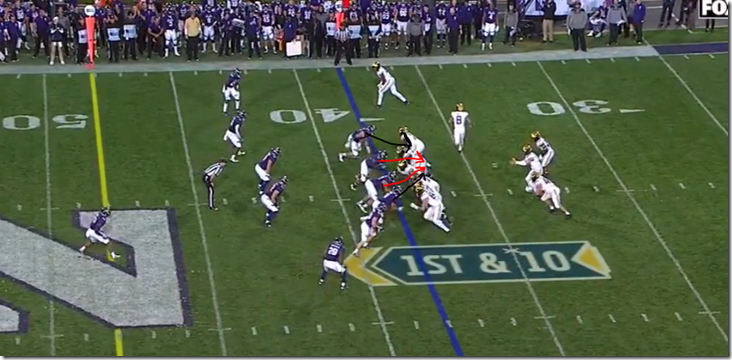

Northwestern slanted a lot in this game and occasionally that meant slanting DTs into the A gaps after giving Michigan a primo look for an Iso. This is the play I used for the canonical splits when explaining Northwestern’s base alignment. They’re not going in those gaps however:

You can zone out of it. Here you can see the slants, with the red lines showing both DTs heading for A gaps.

Onwenu feels it and zone blocks his DT in the direction the guy wants to go. Now it’s B gap run.

The WLB shoots this gap before waiting for a handoff because he thinks they’ve ID’d the playcall and he can blow this up. But Michigan’s fullback still got moving first, and Mason meets that guy in an audible collision. Paddy Fisher was held on the backside because of the slant so he’s stuck behind some trash and Karan again gets a good gain in seemingly no space because every hat is accounted for.

Again: “ISOLATION”—even in a wad of bodies this play is really about what happens with the isolated LB versus the fullback block. The way for the defense to win it is to activate that LB on fullback action:

But of course, that opens up other things (hi Nebraska!).

WHY DID YOU SAY THIS IS RELATED TO DOWN G?

Let’s circle back to last week. Remember the one where the Husker LBs went doink?

Doink

Watch the two middle linebackers as they react to Mason, who (just like 2 plays ago) is really just planning to Wham block the DT that Onwenu ran past. You can’t key the fullback when facing this offense because Harbaugh showed you the fullback is likely to lie.

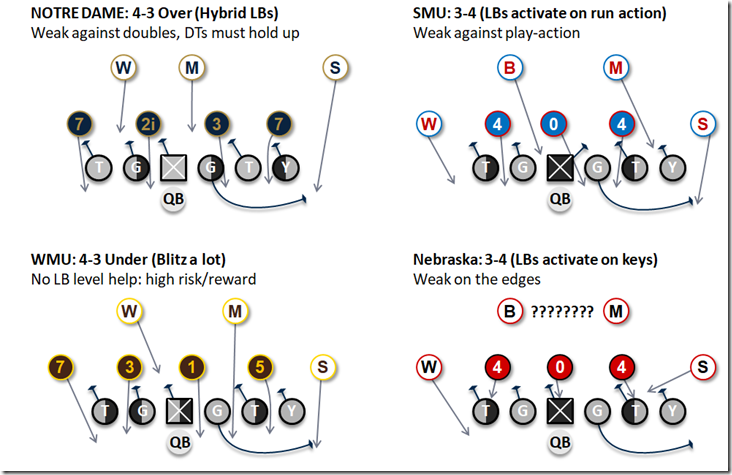

However Northwestern’s 4-3 even alignment is enough to make them strong against Down G. Remember, the Wildcats are sacrificing some interior integrity to reinforce their edges. That is a very different base fronts/approaches of Michigan’s first four opponents (numbers on the linemen are their techniques):

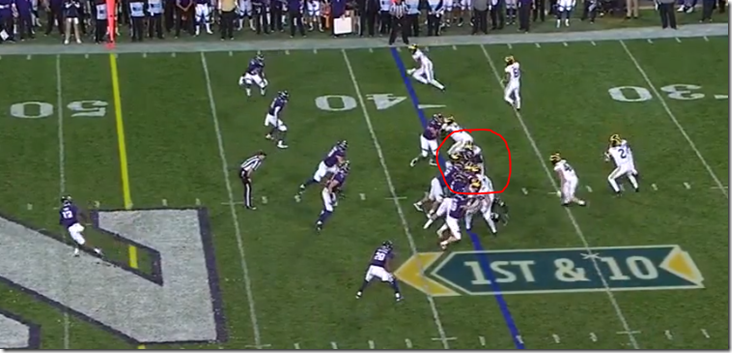

These opponents all gave Michigan a DE on the strong side they could block down with a tight end, and an edge blocker the guard could kick. Let’s see what happens when you try to run it against Northwestern however:

Okay not totally fair because this one caught a slant, but note the guy to kick ain’t no Nebraska OLB wearing #22—the edge of the gap Michigan is attacking is held by The Gaz himself. Bredeson has a much harder time moving him, and then Runyan’s bad block becomes relevant and Gentry getting away with an egregious hold can’t be capitalized.

I’ll give you another Down G event from this game that wasn’t RPS’d:

This is another formation when they showed under and slanted, with the backside going to their Even gaps and the frontside sending the 3-tech into the B-gap (which after the pull is the same as the A gap) and The Gaz into the C gap, with Gallagher replacing on the edge. That should help Michigan since those guys are slanting away from their downblocks. But this is where you see what I mean about strength on the edges. Gallagher isn’t leaping out there, he waits for Bredeson to show then gets a running head start and attacks. After Gallagher comes a run from the safety to take out the crack blocker, further delaying any cut forward. Finally there are no more blockers, the cornerback (who was facing the play the whole time) contains, and one by one every Wildcat gets to arrive at the line of scrimmage.

Sorry those aren’t great examples. But it’s really a good thing we don’t have any because Down G against this kind of team is already going uphill.

The problem is the End. He’s out there to set the edge, and much better positioned and equipped to do so against a pulling guard. Also the Quarters coverage frees the OLBs from having to cover a quick seam from the #2 (reading outside->in) receiver, so they can activate against the run. Also the linebackers’ patience rewards them, as they don’t have to flow backside once they read the guard’s kickout pull. Again: Even is good at guarding the edges.

And that’s fine. Down G was a nice way to power through some soft parts of the schedule after Notre Dame. I haven’t scouted this year’s Maryland but unless they’ve changed sans Durkin I don’t think they do a lot of this. Michigan State will. So it’s nice to know now that if an opponent like that shows a soft belly, Michigan has a way to punch through their gut.

October 2nd, 2018 at 10:46 AM ^

Seth, you should totally write an e-book with each chapter an article like this. These are all excellent.

October 2nd, 2018 at 10:59 AM ^

Yep, completely agree. Very easy to read/understand (and the video assists get better and better) - and I've always appreciated Seth's sense of humor.

October 5th, 2018 at 5:57 AM ^

I actually didn't like Seth much as a writer when he first started. He's gotten MUCH better. I look forward to basically everything he writes now. Great for history and breaking down plays.

October 2nd, 2018 at 10:58 AM ^

really enlightening - thanks for the post Seth

October 2nd, 2018 at 10:59 AM ^

This is some primo shit right here. Not only is the analysis great, but the presentation is easy to follow and very concise.

October 2nd, 2018 at 11:00 AM ^

Such a great post, Seth. Kudos. It's not just nice, to have a fullback who happens to be a good blocker. On many of these running plays, the lead block by the fullback is the single most important block on the play.

October 2nd, 2018 at 11:03 AM ^

Great stuff Comrade.

October 2nd, 2018 at 11:04 AM ^

Not explicitly discussed, but it looks like Ruiz is a pretty good C based on this. Able to get to and seal a good LB like Fisher, that NW counts on to beat plays like this. Hope he can do the same against MSU and Wisconsin who should be another step up.

October 2nd, 2018 at 11:14 AM ^

It seems like our pre-game planning is well thought out. We prep what should work and we prep the counters for the counters to that. No more Borges "fake designed to look like something we never do" plays.

But in-game play calling has been average. Not Franklin level, but not brilliant either.

October 2nd, 2018 at 11:16 AM ^

Great, informative post. Took a lot of work I'm sure. Thank you.

I would love to know whether the repeated running into a wall was simply killing clock in a low risk manner, or whether they were working on something they thought *could* work if blocking etc. was executed correctly. Those "up the guts" seemed so far from having a chance at being successful, not just a subtle block away from a good gash.

October 2nd, 2018 at 12:10 PM ^

Have always - and likely incorrectly - assumed that it was more along the lines of we're going to rep our stuff in low risk scenarios because 1. we're going to rep our stuff, and 2. to set you up for something later.

Manny Ramirez was notorious for taking a called (3rd) strike in order to give the impression that the pitcher fooled him whereas he was quite aware that, more likely than not, the same scenario would resurface soon. And when it did, he would be waiting.

October 2nd, 2018 at 3:11 PM ^

Kirk Gibson often claimed to do the same thing.

October 2nd, 2018 at 8:12 PM ^

One aspect had to be that the "up the gut runs" opened up playaction like crazy. The play action on first downs averaged over a first down everytime they ran it.

October 2nd, 2018 at 9:06 PM ^

You're referring to when they ran power later in the game. When M was killing clock on the drive after taking the lead Northwestern had their linebackerish strong safety blitz the B gap. That'll end your power run right there.

October 4th, 2018 at 9:50 AM ^

Question then: If Northwestern is blitzing the B gap and shutting down the power run, is there nothing else that could be done to counter the blitz and still run the clock out on by keeping the ball on the ground? It seems like we just sorta gave up at that point and kept doing the same thing over and over even though it never worked.

October 2nd, 2018 at 11:17 AM ^

Great post as said. Just a few nitpicks:

One of the graphics says Nebraska, not Northwestern.

Also it's Bell going in motion, not DPJ.

October 2nd, 2018 at 1:10 PM ^

Same, the gifs seem a bit out of sync after about half way through.

October 2nd, 2018 at 11:21 AM ^

Easily my fav segment of the week each week. Great job Seth, and thank you for the insight.

Question - Do Def like NW keep teams honest by flipping this from time to time and have the DTs slant towards the A gaps and bring the MLB and WLB into the B gaps?

October 2nd, 2018 at 11:49 AM ^

Yes, that's a pretty standard blitz from any formation. The answer with any kind of slant involving a lineman moving from one gap to the next gap is "Yes."

October 2nd, 2018 at 11:22 AM ^

Nice job, Seth.

October 2nd, 2018 at 11:24 AM ^

A lot of really good stuff here.

The bigger problem, IMO, with Down G against Northwestern (similar to MSU) is how they play their safeties. The way to stop Down G is to shoot that outside gap. If the EMOL can prevent getting kicked, that alley filling safety can really hold things down, especially because it makes it very difficult to crack him.

The other thing with a 2i technique NT is it's a bitch to zone. It really forces the Center to work laterally in his zone step. That's another reason Down G stuggled here, is that Center has to reach that 2i or the OT has to block down to that 2i which isn't easy on the playside (it's not like blocking back on Power where you can allow upfield penetration because it's away from the play). So a play like this Weakside Iso, where you can just blast that 2i out with a combo to the LB (and here, it will almost always be Ruiz that leaves for the LB, where as zone it would typically be Bredeson) is a great call given the defensive formation/tendency.

Weakside Iso, by the way, does nominally double the NT to strength. On these plays, Ruiz and Bredeson doubled to the MIKE. On the first play, they crush that guy right into the MIKE's lap, which is exactly how you draw it up. That's really one of the best doubles we've seen this year. Just blasted that guy back.

When you talk about how you can "zone it" (may want to check the name; think there's a typo and you meant Onwenu not Ruiz as can be figured out with how you're describing it, but may be confusing to people on first read), you do want to keep that guy in the B-gap and because you do want to keep this an A gap run if at all possible. But most important is to seal him somewhere to give your FB a clear read off your butt. You don't base block with the weakside guard. You try to seal him in the B-gap, and if he crosses face, you better carry him past the A-gap. Part of the problem with that play is Onwenu let him cross his face, which slowed down Mason so that the (now attacking) LB wasn't met with the same force, but the play can still have some success because Mason doesn't have to redirect all the way to where the initial B-gap was, because Onwenu keeps shoving his man down.

Ian Boyd did a nice post about how the Insert Iso is one of the most popular spread schemes. The FB is coming back all over football, and particularly to the weakside, he makes the run game much, much more potent. I love that this is actually from FB depth though (out of gun) and not wrapping an H-back. Think that extra bit of down hill really helps crush the LB on this play.

October 2nd, 2018 at 11:28 AM ^

This is fantastic. Thanks so much. Makes me understand why people say Harbaugh's offense is boring. They don't understand it. It's like taking some chess pieces, putting pads on them and letting them go at it!

October 3rd, 2018 at 5:32 PM ^

I am sure the coaches of the opposing team's appreciate his creativity and knowledge

October 2nd, 2018 at 11:44 AM ^

These posts are every bit the same premium content that UFR's are! Thanks, Seth, this is always good stuff!

October 2nd, 2018 at 11:49 AM ^

I <3 neck sharpies

October 2nd, 2018 at 11:52 AM ^

Excellent writing and really interesting. Thanks Seth! I learn so much from this site. Now if I could only find a way to put it to any use.

October 2nd, 2018 at 12:00 PM ^

Higdon needs to buy Mason a nice steak dinner ... Lordy can that boy hit like a sledge hammer or what?

October 2nd, 2018 at 12:35 PM ^

... a nice steak dinner... in the dorm cafeteria because he is an unpaid student-athlete.

/fixed it for you

/you're welcome

October 2nd, 2018 at 12:22 PM ^

I WANT MY LOLLIPOP!!!

And not a poopy flavored lollipop...those are worthless.

October 2nd, 2018 at 12:51 PM ^

If Ben Mason can add some receiving threat to his arsenal, then he's going to be a true shutdown fullback. Dudes a hammer

October 2nd, 2018 at 1:09 PM ^

Excellent.

October 2nd, 2018 at 3:19 PM ^

Honestly dude. What everyone said above. I regret to say I've always skimmed the Neck Sharpies and FFFF posts. But for some reason I read this one and it's incredibly done. Thank you for taking the time to do these. I'll be coming back for the next one!

October 3rd, 2018 at 2:16 AM ^

I feel like this one was much easier to understand than previous ones

October 2nd, 2018 at 3:19 PM ^

I enjoy these posts more than any post game content on any site I visit. Your graphics are crystal clear and you use pictures and clips to great effects

more than RVB/Balas/Skene, more than the MGopodcast, and more than Sam Webb/MMQB, I look forward to this post.

Now I feel like I better understand why Down G before, why not Down G in this game, and how the coaches planned to run the ball taking NU specifically into account.

I still don’t know why the 1Q was so tough or why M could only muster 20 pts but the UFR may explain that clearly especially now that I get this concept.

October 4th, 2018 at 10:05 AM ^

Just so I'm 100% clear, "Down G" is where one of your guards pulls and kicks to the outside of the line as a blocker right?

October 2nd, 2018 at 5:04 PM ^

This is the kinda stuff you miss during the game as you wonder why Michigan runs into a brick wall at times. Run game has tons of complexity. Hope they have more in their bag of tricks. Love me some Mason.

October 2nd, 2018 at 5:30 PM ^

Seth, your Neck Sharpies work this season has been phenomenal. Accessible, intelligent, clear...just amazing.

Fans should only have to think back to last year's MSU game to remember that ISO did, in fact, create lots of problems for their defense before we decided we should start passing every play in a hurricane.

This OL is equipped to make opposing defenses pay for leaving their middle exposed, and Ben Mason seems to win every block. I'd expect ISO to be very useful as the season goes on, and ISO sets-up Counter.

If Shea will be allowed to run, combing Down G, Counter, and ISO concepts could be devastating. It's worth mentioning that this ISO play with Bell running across the formation is an RPO where Shea is optioning the safety. For folks looking for a true spread offense, we are dangerously close with some of these looks, yet still maintaining some power concepts. Very Harbaugh.

October 4th, 2018 at 10:10 AM ^

One thing I've been wondering this season is, how often are we actually exercising the available option? I feel like (and correct me if I'm wrong here) that we often give the appearance of an RPO but usually just go forward with the primary design of the play. If this is true, and we hardly ever actually exercise the available option, then is it A) truly an RPO and B) an actual threat the defense needs to worry about?

So like, in my mind, when I think about more spread teams that use these sort of option plays, it feels like you never know who's getting the ball or if the QB will tuck and run it because they're constantly doing something different. Whereas our RPOs seem to be almost always executing the designed run play and never executing the option. Am I off-base on this?

October 2nd, 2018 at 6:51 PM ^

Maybe one of the best Neck Sharpies you’ve ever written, at least that I’ve read.

October 2nd, 2018 at 7:18 PM ^

Great analysis, again!

October 2nd, 2018 at 7:34 PM ^

"And Ruiz is large." Dunno why, but that got me absolutely rolling haha

October 2nd, 2018 at 11:40 PM ^

This is a great article. I had to read most of it three times to fully appreciate it. In fact this whole season’s neck sharpies have been great. I really like how you present the basics as well. The jargon descriptions have advanced my understanding of the game.

October 2nd, 2018 at 11:42 PM ^

Seth,

Thanks as always. These are fantastic.

October 2nd, 2018 at 11:42 PM ^

Seth,

Thanks as always. These are fantastic.

October 3rd, 2018 at 7:50 PM ^

Superb content. Superb analysis.

October 5th, 2018 at 10:22 AM ^

This is so well-written!!! Full on context, examples and few assumptions. Please!!! keep writing these.

Comments