Hokepoints: What’s a Spread Punt?

Takeaway: offenses were so potent by the 1950s that teams would punt on normal downs to gain field position, and the opponent wouldn’t have a guy ready for this.

Michigan’s outmoded punt formation is a horse we’ve been beating since Hoke’s first year despite it being about as dead as, well, NFL-style punt formations in college football. In light of last week’s punt-o-rama first half I got a question from a reader asking if we’d actually explain what the difference is between them and why one is better than the other.

So yeah, let’s do that, with the foreknowledge that Hoke isn’t going to change no matter what we say or prove; this is so you’ll know what you’re seeing only.

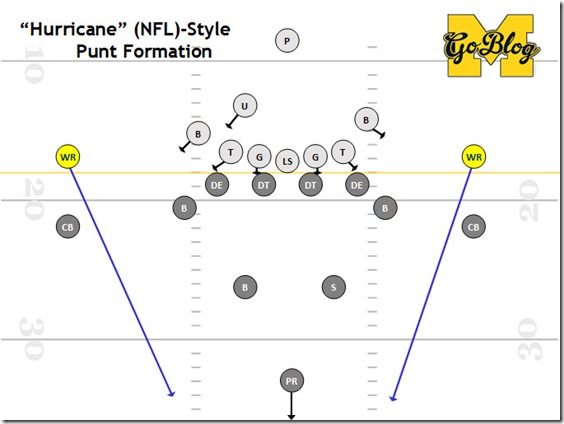

Here’s the punt formation that Michigan uses:

Like all things in football there’s a hundred different names and minor variations on it but the gist has remained the same since a time before the word “pattern” was replaced with “formation.” It follows the same rules as normal downs: seven men on the line of scrimmage, four in the backfield, with the backs plus ends on the line counted as eligible receivers. Since the snapper has to concentrate on that he typically doesn’t figure into the punt protection scheme except as a bonus dude to get in the way or cover a lane. The O-line does the front-line blocking, with a couple of wingbacks to protect against an edge rush and an up-back on the “leg” (…of the punter) side to catch anything that comes through, like an RB in pass pro, reading inside-out.

This protection scheme has worked for two generations and remains pretty safe from all kinds of punt blocking attacks unless a block is blown. It packs guys in the middle and on the outside the blockers mostly just have to keep rushers from getting inside before the punt is off. The two “ends” (wide receivers, really) are gunners, releasing downfield on the snap to attack the returner before the ball arrives and he can set up his blocking.

The NFL still uses this formation because they have to:

During a kick from scrimmage, only the end men, as eligible receivers on the line of scrimmage at the time of the snap, are permitted to go beyond the line before the ball is kicked.

Exception: An eligible receiver who, at the snap, is aligned or in motion behind the line and more than one yard outside the end man on his side of the line, clearly making him the outside receiver, replaces that end man as the player eligible to go downfield after the snap. All other members of the kicking team must remain at the line of scrimmage until the ball has been kicked.

Translation: only the two outside guys can be gunners; everyone else on the punting team can’t release downfield until ball leaves foot. This was an attempt to cut down on injuries, figuring it’s best to keep as many collisions between high-speed NFL bodies to short range meetings in the backfield.

[After the jump: niche opportunity leads to adaptation]

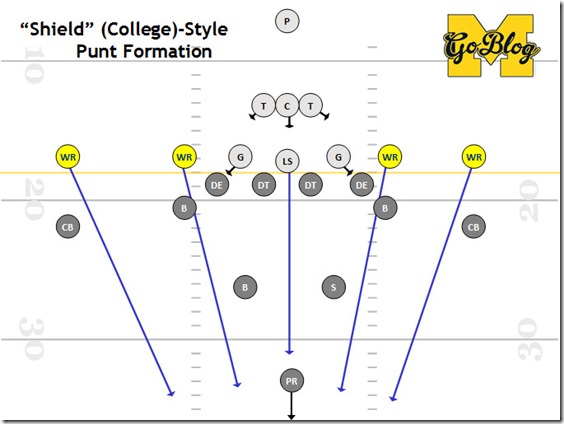

College football doesn’t have this rule, and that’s why a different punt strategy could evolve:

The two most common names for this style are instructive. It’s “spread” because you wind up with guards lined two yards away from the snapper, and four “receivers” (ie gunners) instead of two. It’s “shield” because the key to it is setting up 900+ pounds of meat shield about five yards in the backfield, behind whom the punter can do his thing. From a personnel standpoint you are basically trading three fullbackian guys for two WR/DBs and an extra OL.

Why only college? Without the NFL’s two-gunner rule college teams are free to send as many dudes as they like toward the punt returner right on the snap. The only thing holding them back is having to block long enough to get the punt off safely against all fronts. So: how do you get more guys released? They tried various rugby-style things in the ‘90s, but the real winner was going to a defense-in-depth strategy that required two (!) fewer blockers to get the same (actually better) rate of preventing blocks. The only tradeoff is less opportunity to pull a fake pass; that happens so rarely it’s not much of a loss. In the pros, since you can’t send covered ends downfield anyway, might as well stay in a normal-ish offensive formation.

The key difference is how they block the A-gaps (the spaces between the center and the guards). In a shield punt the A gaps aren’t defended at the line of scrimmage. Rather you have three very large men—who can thus absorb a rusher without giving ground—standing about five yards back. They act like a gate: they line up with a space for the ball to be snapped, then close ranks. Those three guys are responsible for catching any defender that comes through the A gap, and keeping whatever else leaks through too far outside for them to get to the punter.

Provided they do their job—more of which than any coach would care to admit being to stand in the way and be large—there should be a nice 7-yard cushion behind them for the punter to step into and get the ball off. Provided the shield isn’t shoved backwards, in the time it takes for the defenders to engage then break through or around them, the punt will get off.

With the eye of the storm kept clear by that mechanic, the rest of the blocks are quick and need only widen the vectors of the non-middle attackers. The guards’ jobs in particular are to get inside the ends and shove them a yard horizontally; then they too can release downfield to join the punt coverage. The punter receives the ball about 12 yards behind the line of scrimmage, and those seven yards in front of him are his safety zone to step into; the punt release point is right behind the shield.

The only way to beat it is to swarm the shield. If you can’t figure out why this scheme scares coaches, look again at the five people on the line of scrimmage: there’s extra WRs on the line instead of offensive tackles. Until they could see it working at other schools, many a coach probably got to the point where you say “don’t block the DTs at the line” and walked out of the meeting.

Even if you told him a punt is your highest yardage offensive play.

If the defense packs more guys onto the line, you close up and put a hat on a hat, still leaving the three most dangerous attackers for the shield. If they have four attackers in the A gaps, the guard to that side will change his technique, blocking down on an inside guy to delay anything behind that block (the shield takes care of the DE). The result is twice as many gunners heading downfield at the snap to cover the punt.

To date defenses have yet to find a method of consistently getting pressure, even on an all-out 10-man attack, unless the blocking is screwed up or the punter doesn’t get the ball off in time.

Faking is a bit harder to do because you technically have two tackles (the covered inside WRs) downfield. NCAA refs let that go to extraordinary lengths when it’s lumbering dudes wearing numbers in the 70s; not so much when it’s a guy wearing 85 running downfield like it’s four verts. You’ll note when Michigan was a shield punting team we had the punter just run it.

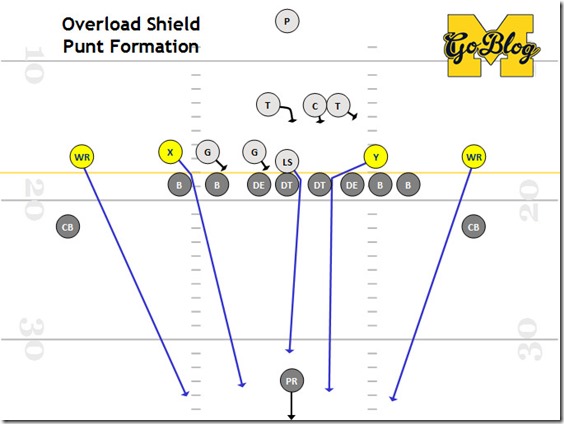

There are variations. One tinker gaining popularity is to run it from an unbalanced line, blocking hat-for-hat on the side you’re punting to and saving the shield for the backside.

That’s an overload formation by the way, but it’s a good example of how the shield punt’s rules translate to the defense trying to get pressure:

The Y receiver just has to run across the formation and bang the DT to interrupt that whole side; four guys do get into the three-man shield, but the unblocked dude is the furthest out and therefore can’t cover the horizontal difference before the punt’s away. On the frontside, everybody blocked down—so long as they got a hat across the defender there’s no way that guy’s getting upfield fast enough to cover the punt.

How do you know it’s so effective?

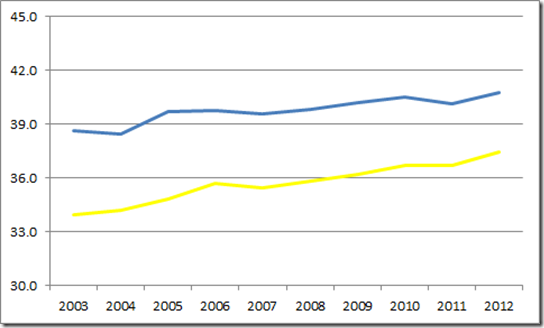

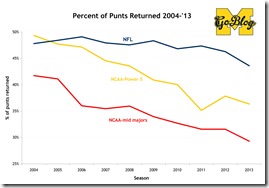

Data (click bigs):

Nothing else—no rule change or game mechanic—has changed punting in this period except the spread of spread. Mathlete’s looked at it before too. The above were from data grabbed at ESPN. See trends? The likelihood that a punt will be returned has dropped 30%. Those that do get returned are getting 15% fewer yards. I split out the Power 5, since they’re generally working from the same pool of punters as the NFL, and watched the rate of their punt returns drop from the NFL normal to less often than the mid-majors, with their non-power legs, used to get.

Because it can protect the punter so successfully, and moreso because it can get so many tacklers downfield before the blocking, the spread punt has made successful punt returns a rare thing. We saw a case example of the spread punt’s efficacy last week in Ann Arbor. Miami (not That Miami) managed to get what seemed like the same value from their punts as Michigan despite their punter’s leg having a range that didn’t even get to Norfleet. Last week Michigan missed an opportunity on a muffed punt against ND precisely because they only had one guy downfield to challenge for it.

So why doesn’t Michigan do this? The best reason I’ve been able to come up with is maybe they don’t want to put any more on their offensive linemen right now? That is a bad reason; teams that have transitioned to the spread punt did so in a few practices and were effective at it. The real reason is probably that they want to be Alabama, i.e a pro team in college uniforms. Punt blocking isn’t all that hard; you just need to get in the way of interior rushers and delay the outside dudes. The biggest way to screw it up, from a coaching perspective, is to be the last program on the continent to adapt to a superior method.

September 16th, 2014 at 12:11 PM ^

You only snark the ones you love.

Don't forget I predicted Michigan would go 10-3, losing all three rivalry road games and winning the rest and our mid-tier, New Year's bowl game.

We're three games in and so far my prediction is holding. And, all snark aside, I'll take that as a good year despite the frustrations the three losses will bring.

September 16th, 2014 at 1:08 PM ^

September 16th, 2014 at 12:05 PM ^

Thanks for the charts.

I'd love to see Michigan (i.e. returns against Michigan) plotted in the same format.

I also wonder how easy it would be to chart out teams that have adopted the spread/shield versus teams that have not.

In my spare time, I guess.

September 16th, 2014 at 12:16 PM ^

September 16th, 2014 at 12:22 PM ^

Shorter punt return yardage is nice but what is the net punt average?

September 16th, 2014 at 12:41 PM ^

| Year | mid-major | Power 5 |

|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 34.9 | 35.6 |

| 2005 | 35.5 | 35.4 |

| 2006 | 36.0 | 36.1 |

| 2007 | 36.8 | 36.2 |

| 2008 | 36.9 | 36.1 |

| 2009 | 37.5 | 36.8 |

| 2010 | 37.7 | 37.7 |

| 2011 | 37.7 | 37.8 |

| 2012 | 38.3 | 37.5 |

| 2013 | 38.6 | 38.0 |

Although there's a lot of noise in those numbers because offenses have gotten way more successful at moving the ball from their side of the field due to offenses going spread. Mathlete could adjust for that with play by play data but this isn't PBP data above.

Net punting just has so much involved in it that it's not a reliable statistic. What I did notice is that punting length seems to be up (linearly) 1 yard per punt, so the movement in net punting has primarily been happening on returns. In the NFL it's the opposite: net punting is up because avg punt length has gone up by 4 yards, but return length has grown in recent years, so the result has been about 1.5 yards gained in net. This says that punters have gotten better at booming punts, especially in the NFL, and that his has correlated with longer returns in the NFL but not in college.

These data support a hypothesis that punts are longer in general, but that spread punting in college football has been cutting down on the frequency and success of returns.

September 16th, 2014 at 12:24 PM ^

This graph in the link to the Mathlete's analysis shows gross punting (blue) and net punting (yellow) over time as the shield punt as become more prevalent. Also in his analysis, it shows blocked punts have decreased from 2.6% to 1.0%.

September 17th, 2014 at 10:32 AM ^

September 16th, 2014 at 12:16 PM ^

we quit doing special teams coaching and strategies about 10 years ago

September 16th, 2014 at 1:36 PM ^

September 16th, 2014 at 1:48 PM ^

kick, it was a disaster, two punts blocked against Iowa I think, said special teams coordinator took a "leave of absense" the week after the game.

Doesn't feel like Michigan's had good special teams since.

September 16th, 2014 at 12:29 PM ^

September 16th, 2014 at 12:57 PM ^

The difference is in who's releasing. Hurricane punting leaves your fullback/tight end/safety types in to catch the edge blocks before they release; often the first guys to leave because they're uncovered are the offensive linemen. In spread punting you've put four wide receivers in position to release immediately, and your last wave are 300 pound blocky dudes.

It can be an up or down decision even if there are good things to recommend dinosaur punting, because it's a net: at the end of the day the benefits of spread punting are greater than the benefits of hurricane punting, therefore the question is black or white.

September 16th, 2014 at 1:15 PM ^

September 16th, 2014 at 2:50 PM ^

Spread should refer to the college version. I know people call the hurricane that but spreading out the OL and having a more receiver-ish personnel group, plus the shield is referred to more often as spread.

Just say NFL style and Shield, I guess. Or dinosaur and spread.

September 17th, 2014 at 7:13 AM ^

You mentioned that twice. Why won't the NFL use it then? Sure, they can't release the guys down field early like in college, but you just said it protects your punter better and gives you two extra gunners?

September 21st, 2014 at 1:27 PM ^

The inside guys on the line aren't allowed to release downfield. So the receiving team can bring pressure without worrying about those guys as passing threats, or back off and not worry about those guys racing past them downfield.

So you're stuck in the NFL with five offensive linemen on the line. If you turn three guys in the backfield into blockers as well you've taken a lot of speed out of your punt coverage.

Also the NFL has some ludicrously good pass rushers all over the place, so the shield is more likely to be destroyed.

One last reason for its popularity in college (doesn't affect the pro): college football had the shield punt a long time ago but teams stopped using it because the defense (punt return) team would have the first guy to the shield just cut (dive at the legs of) the shield defenders. UNLV brought back the shield punt right after the NCAA ruled that out. I think the NFL has a similar rule so that doesn't answer why pro teams don't shield so much as why the shield took all this time to gain popularity in college.

September 16th, 2014 at 1:38 PM ^

Seth,

Great summary! I learned a lot from your summary and the attached videos. Keep these types of posts coming.

September 16th, 2014 at 2:06 PM ^

Hoke gave some insight on his thinking on this during his radio show last week. Brandy asked for questions from Twitter and it came up:

Hoke asked about why he doesn't use the spread punt: "I've always been a pro style punt (coach). ... I really don't want to talk about it."

— Nick Baumgardner (@nickbaumgardner) September 10, 2014

Hoke says Michigan's a pro style punt team because that's what suits Will Hagerup best ... — Nick Baumgardner (@nickbaumgardner) September 10, 2014

Hoke's response included the concept that Hagerup's "got a real big leg," which...OK? But it would seem to me that a punter having a real big leg would be a factor in favor of getting as many gunners downfield as possible to corral a returner in the extra space downfield created by said booming leg. If your punter sucks, your gunners have a lot less room to cover to get to a returner.

(Edit: Whoops, hadn't seen that Brian had quoted the first tweet in his earlier UV post. Oh, well. Leaving it here for posterity.)

September 16th, 2014 at 2:29 PM ^

Why on earth would the kicker matter? Unless you've got a dude who kicks so low he'd whack the shield guys in the head (which is really bad), both formations treat the kicker equally.

September 16th, 2014 at 2:41 PM ^

Saying "I don't want to talk about it"is the same as saying "I have no clue why I continuously choose to do this"

September 16th, 2014 at 3:19 PM ^

September 16th, 2014 at 3:50 PM ^

Is that what we're trying to do?

September 16th, 2014 at 6:04 PM ^

September 16th, 2014 at 4:25 PM ^

But it shouldn't be hard to justify it if he has an actual valid reason for doing it. So far the only reason he has provided is featuring his punter, which is crap, which is why it keeps coming up.

September 16th, 2014 at 11:44 PM ^

September 17th, 2014 at 10:49 AM ^

September 16th, 2014 at 6:31 PM ^

September 16th, 2014 at 11:50 PM ^

One thing I've been wondering about in recent years--especially when I was screaming at the TV after the end of the second half debacle against Miami when Hagerup's punt landed 8 yards deep in the endzone--is why don't teams ever punt out of bounds anymore??

I remember the old "coffin corner" strategy when a punter would angle himself and aim at simply kicking the ball to the sideline within the ten yard line (which seemed to work most of the time), instead of the low percentage play of pinning one deep directly in front of the goal line and relying on the gunners to frantically keep it from bouncing over that threshold.

September 16th, 2014 at 11:51 PM ^

Comments