Fee Fi Foe Film: Air Force

Michigan faces one of football's most distinctive offenses, the Air Force triple option, this weekend at the Big House. To get an idea of how the Falcons operate on both sides of the ball, I went back and watched their matchup with Notre Dame from last season, a 59-33 victory for the Irish. How can Michigan slow down the powerful Air Force rushing attack and take advantage of their 3-4 defense? Read on for the breakdown.

OFFENSE

Spread, Pro-Style, or Hybrid? None of the above. The option offense deserves its own category. Air Force operates primarily out of the flexbone and I-formation, and the design of their offense revolves almost entirely around the threat of the triple option.

Basketball on Grass or MANBALL? Both, actually. The option requires linemen, backs, and receivers to carry out a very specific set of blocking assignments, and those change depending on the defensive alignment: Tremendous has a great breakdown of when Air Force goes zone and when they utilize "veer" blocking—the rule of thumb is they go zone against 7-man fronts and veer against 8-man fronts. Air Force—whose starting linemen weigh an average of just 255 pounds—also requires their players to cut block like they're the '98 Denver Broncos. Mind the knees, boys.

Hurry it up or grind it out? A new category this week, as it was an oversight to not include a section on the pace of each team's offense. Air Force rarely huddles, utilizing a fast tempo (61.4% adj. pace in 2011) and a variety of formations that they run with the same personnel to catch defenses off guard and keep them from making substitutions. Here's an example from the Notre Dame game; Air Force runs a fullback dive from the flexbone, then quickly transitions to their triple-stack I-form and gets a big gain from another fullback run:

Just 22 seconds elapse from the time of the first snap to the second snap, yet Air Force is able to run from two entirely different formations while utilizing the same personnel group. It's paramount that the defense get their plays in quickly and communicate between snaps or the Falcons will eventually break one big.

Quarterback Dilithium Level (Scale: 1 [Navarre] to 10 [Denard]): Falcon senior QB Connor Dietz started three games as a redshirt freshman in 2009 and has otherwise served as a backup until this season. He did see the field some last year, averaging 6.6 yards on 38 carries, and rushed for 74 yards and a touchdown on seven carries in Air Force's season-opening win over Idaho State. The Falcons produce system quarterbacks and Dietz fits that mold; he isn't an elite athlete, and in an offense that relies on ruthless execution that doesn't prevent him from amassing some pretty impressive stats. I'll give him a 6, which turns into a functional 7-8 when the offense gets rolling.

Dangerman: The beauty of this offense is it doesn't rely on any one player to bear the load—14 Falcons tallied at least one carry against Notre Dame, 11 against Idaho State. If I must choose a focal point, however, it's running back Cody Getz. The flexbone formation features a fullback—or "B" back—lined up behind the quarterback, with two wing-backs—"A" backs—on the end of the line, a step back from the line of scrimmage:

Getz is one of those "A" backs (SB in the graphic above)—he's usually the pitch option and often motions into the backfield before the snap. While he rushed for just 102 yards in 2011, he's already surpassed that total in 2012 after picking up 218 yards and three touchdowns on 17 carries in the opener. At 5'7", 175 pounds, Getz is by no means big, but he's a senior well-versed in the system and has the speed to make teams pay for giving him the edge.

Zook Factor: Air Force head coach Troy Calhoun—a former Falcon quarterback under the tutelage of Fisher DeBerry—knows his team must play aggressive to overcome size and talent deficiencies, and therefore will never be confused with Ron Zook. In just the first half, the Falcons go for 4th-and-2 the ND 32, attempt a surprise onside kick, go for 4th-and-2 from their own 42, and successfully fake a punt on 4th-and-6 from their own 35.

After one half of football, I'm already a huge fan of Troy Calhoun.

OVERVIEW

It's no secret that Air Force will run, run, and then run some more. Last year, they ran 81.9% of the time on standard downs (national average: 60.0%) and 61.1% on passing downs (33.3%). The offense is designed to get positive plays on every down and stay "ahead of the sticks"—maintaining reasonable down-and-distance situations so the run is still the primary threat. Air Force finished in the top 37 nationally in all three advanced rushing stat categories (S&P+, Success Rate, PPP+) and were a top-60 offense, but on passing downs their efficiency plummets near the bottom of the national rankings. The key to stopping the Falcons is forcing them into obvious passing situations; this is, of course, much more difficult than it sounds.

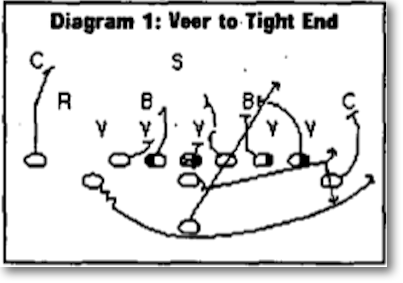

The basic play of the Air Force offense is the veer option. Fisher DeBerry's entire 1998 Air Force playbook is available online; this diagram comes straight from its pages:

Before the snap, one of the "A" backs (in this case, the one on the left) motions into the backfield, arcing behind the fullback and into a pitch relationship with the quarterback. The first read is the dive to the fullback, and if option coaches had their druthers this is where the play would go every time. If there isn't a crease for the fullback to run through the A gap, the quarterback pulls and heads for the edge, where he'll read an unblocked defender—in this case, the right defensive end. The quarterback can keep or pitch it outside to the "A" back.

[For the rest of the breakdown, hit THE JUMP]

You can see Air Force run this very successfully at the 1:35 mark of the video below, as well as a variation from the triple-stack on the very first play. The whole video gives you an idea of just how versatile the option can be, as Air Force runs both the triple and speed option plays out of a variety of formations. [HT: Smart Football]

Air Force can also change their blocking assignments from play to play depending on how they're being defended; if the safety is coming up to tackle the pitchman, they can send a blocker to take him out, and now the defense must come up with a new strategy. This is what makes stopping the triple option attack so difficult: the offense can make dozens of adjustments on the fly as a reaction to the defense. Against a well-coached, disciplined team like Air Force, no one play or strategy acts as the magic bullet to stop them.

There's also the midline option, where the quarterback chooses whether or not to give based on the defensive tackle (via Smart Football, again):

Oldmid by phatphelix

Regardless of the specific play, the option offense—much like Rich Rodriguez's read-option spread—is designed to leave unblocked defenders in a position where no matter what they do, they can't be right as long as the offense executes their reads. Leaving defenders unblocked allows their linemen to double-team key defenders and reach the second level.

From the basic option Air Force can begin to branch out. The motioning "A" back can receive a quick toss, hitting the edge much faster than an option would. The Falcons run a fair amount of zone stretch plays to their fullback (from the flexbone) or tailback (from the I-form). They also utilize the speed option, especially from the I-form.

There are very few straight-forward passing plays in the Air Force offense; most of their passes come off play-action, and many have some serious misdirection built in—I'll get to that in the play breakdown section.

How does a team defend the triple option? Playing disciplined, for one; the triple option touchdown from the flexbone against Houston above shows what happens when a player blows an assignment, in this case the cornerback taking the QB instead of the pitch. For players unaccustomed to facing the option, not attacking the man with the football when he's just a few yards away can be very difficult.

Greg Mattison is normally pretty blitz-happy, but that's not ideal against this offense, as the last thing the defense needs is to send players flying past the football. It's more likely that Michigan will sit back in a simple man-to-man defense and roll Jordan Kovacs up into the box—he'll be key in defending the edge, and that should give you the warm fuzzies.

Unfortunately for Michigan, one of the biggest keys in stopping the triple option is getting great play out of the nose tackle, who must hold his ground to prevent the fullback from simply pounding it inside for four yards on every play. This will be a great game to evaluate which of the Wolverine nose tackles—Quinton Washington, Richard Ash, and Ondre Pipkins—deserves to see the most action going forward.

Finally, the defense must try to take something away from the offense—in essence, turn the triple option into a double option. Whether that's packing the middle to stymie the fullback or bringing up the safety to lock down the edge is up to the defensive coordinator, and deciding what to take away depends largely on offensive adjustments. This will be a three-hour chess match between Calhoun and Mattison.*

-------------------

I must credit several great posts with helping out with the above: a Boise State primer on defending Air Force, Dawg Sports preparing to face the Georgia Tech triple option, and an article on stopping GT from a GT blog.

PLAY BREAKDOWN

Air Force's offense gets teams so focused on stopping the run that they can then strike for big chunks with play-action. In this play, they come out in their standard flexbone set and motion one of the "A" backs into the backfield. The quarterback fakes the toss and is able to hit his tight end for a big gain:

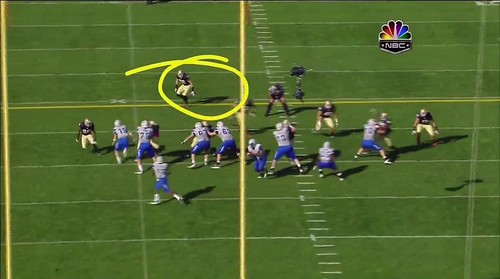

Notre Dame safety Harrison Smith is responsible for getting outside and—I believe—taking care of the quarterback on the option. This play exploits that assignment by getting him moving in one direction, then bringing the "A" back across his face. Here's the initial setup just before the snap—Smith is the one-high safety at the top of the screen:

Air Force's quarterback turns and fakes the toss, and Smith (circled) is already moving to the left. His man, #15 on Air Force, begins to go into his route, though at this point he could just as easily be heading out to block Smith:

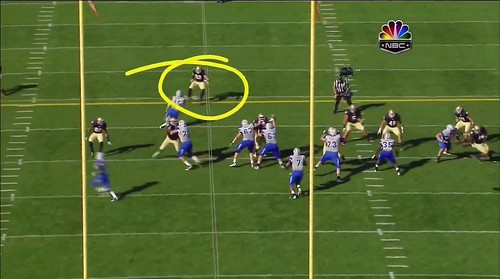

By the time Smith realizes it's a pass play, he's hopelessly out of position. Look at all the open space to the right:

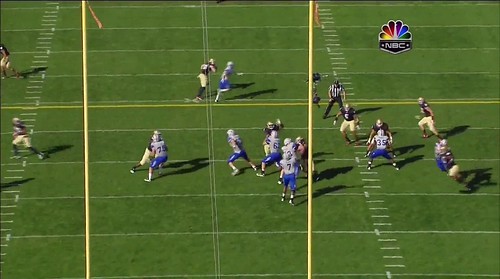

It's an easy completion as #15 heads right into that opening:

That's about as easy a 24-yard completion as you'll see. Air Force actually ran this play on first down, making the very safe assumption that Notre Dame would be in man coverage and expect to see the run.

DEFENSE

Base Set? 3-4. Sometimes an outside linebacker will play with his hand down, but for the most part the Falcons run a basic 3-4.

Man or zone coverage? Air Force mixes up straight man-to-man with a fair amount of Cover 2. The most notable aspect of their coverage is the amount of cushion they tend to give: a great deal, as you'll see below.

Pressure: GERG or Greg? The Falcons need to send extra men to create pressure, though they tend not to get over-aggressive—they'll normally send four or five rushers.

Dangerman: Air Force only returns four starters from last year's defense, and Bill Connelly identifies their two outside linebackers—Alex Means and Jamil Cooks—as the stars of the defense due to their ability to funnel plays back into the inside linebackers:

Means and Cooks are, it seems, outstanding OLBs -- not only did they most likely help [2011 leading tackler Brady] Amack out to a great degree, but they combined for 17.5 tackles for loss, 8.5 sacks, four forced fumbles and four passes defended. The problems for Air Force, of course, are twofold: 1) Means and Cooks account for half of Air Force's returning starters (the only others: end Nick Fitzgerald and safety Anthony Wooding, Jr.), and 2) aside from big-play prevention on the ground, Air Force's defense ranked in the triple digits in just about every other major category.

As you can see, defense isn't Air Force's strongsuit.

OVERVIEW

Air Force is woefully undersized on defense, which dictates much of what they do. Starting nose tackle Cody Miller weighs just 260 pounds and is flanked by defensive ends weighing 240 and 265 pounds each; frequently-used backup nose Nick DeJulion tips the scales at just 240, which Michigan would consider undersized for their weakside DE spot.

This results in teams running roughshod over the Falcons. Despite doing a good job of preventing big plays, they gave up 4.96 yards per carry in 2011, and Notre Dame gashed them for 266 yards on 9.6(!) ypa in their matchup last season. This is the ultimate bend-but-don't-break defense, as evidenced by where their defensive backs line up [click images to embiggen]:

That's not a cushion. That's the whole damn couch.

Not surprisingly, Notre Dame took to the air to exploit the huge swaths of field left open in the flats and underneath. Their first play from scrimmage was a quick screen to Michael Floyd which went for an easy ten yards. Subsequent bubble screens found lots of room to run. Yes, Al Borges finally debuted the bubble screen last week, and I expect he'll utilize it even more on Saturday.

The Irish found success in just about everything they tried, actually, as long as they didn't get greedy and go for big plays. Air Force stays in that deep shell precisely so teams must put together long drives to score, hoping for a turnover or a couple bad plays to keep teams from marching up and down the field. That being the case, Notre Dame threw often to the edge and underneath, picking up lots of 8-10 yard chunks on crossing routes that came under the Cover 2. Runs up the gut or off-tackle worked to great effect as Notre Dame's offensive line physically dominated the undersized Air Force defense.

PLAY BREAKDOWN

One way to create big plays was to run some sort of misdirection, as the back seven of Air Force has to flow hard to the play to make up for their lack of size and athleticism. On first down, Notre Dame takes advantage of this by running a reverse to Theo Riddick, picking up a first down despite missing a downfield block that could've sprung the play for much more:

Let's look at the full setup—here's the pre-snap look, with Air Force threatening to blitz the corner on the bottom of the screen:

Immediately after the snap, Notre Dame's center slips past the nose tackle and heads straight for the inside linebacker on the near side:

Before the pitch even occurs, Air Force's defensive end is walled off from getting back to the top of the screen, and the right guard and right tackle have done the same to the blitzing corner and outside linebacker. The nickel back playing the slot up top is heading in the wrong direction, and the safeties are 20 yards downfield:

Just a moment after Reddick takes the pitch, there's just one Air Force defender on the top half of the field who's within 20 yards of the line of scrimmage, and Notre Dame's left tackle (#70, right in the middle of the field at the 41) has slipped his block and is heading that direction. The inside linebacker has been completely sealed off from the play by the center:

From here, Reddick easily turns the corner against a slower Air Force defender, and only a missed block by #70 on the cornerback keeps this from being a huge gain:

For Michigan, they key here is simple: the running game should find lots of holes, and Jeremy Gallon could have a field day in the screen game. Borges didn't run much misdirection against Alabama, but he could decide it will have much more success against Air Force. The Wolverines should have no problem moving the football on Saturday.

September 5th, 2012 at 3:10 PM ^

Does anyone else see the irony that AIr Force only throws the ball ~20% of the time?

September 5th, 2012 at 3:20 PM ^

September 5th, 2012 at 3:28 PM ^

Looks like happy hour came early in LA

September 5th, 2012 at 3:36 PM ^

September 5th, 2012 at 3:54 PM ^

but Beezlebub plays Jagged Little Pill on continual loop. Now isn't that ironic?

September 5th, 2012 at 3:55 PM ^

September 5th, 2012 at 6:09 PM ^

lack of irony but now I am just confused.

September 6th, 2012 at 12:26 PM ^

It's like rain on your wedding day.

September 5th, 2012 at 3:42 PM ^

Don't ya think?

September 5th, 2012 at 3:58 PM ^

I don't know why cut blocks haven't been outlawed yet. They have to cause more knee injuries, don't they? I don't have any data to back that up, and maybe the rules committee does, but it seems like this has to be leading to more injuries.

In a sport where knee damage is so prevelant, you have a common practice that exacerbates the problem. Not just AF, because I know our team cuts on certain plays, as do all. But I watched that Georgia Tech game Monday night and became immediately concerned about our players. It seems ridiculous that they'll have to worry about people diving at their knees for 60 minutes.

September 5th, 2012 at 4:08 PM ^

and Georgia Tech's coach stood up at media days this year and asked if anyone had a DL hurt last year by a GT cut block. He said specifically they cut and do not chop. No coach could say yes. They all still complain about it though. Can it be more dangerous? absolutely, does it have to be? I dunno about that.

September 5th, 2012 at 5:13 PM ^

We cut in high school, but we were coached to hit the thigh with our shoulder pad. I almost want to say it was the rule, but I don't remember any penalties for cutting at the knees. Long time ago

But the GT OL looked like knee-seeking missiles. And Mike Martin's injury 2 years ago was the result of a cut, though of course he could have been hurt on a regular play.

If they have data that says no more prone to injury, fine. If they don't, they should get the data. It looks really dangerous.

September 5th, 2012 at 7:37 PM ^

Mechanically, it's actually pretty hard to injure a knee with a shoulder.

If the cut block is at the thigh you flip the guy over -- or get kicked in the ribs. It'll hurt and there is a risk of injury to the knee or neck, but it's not remarkable. If the hit is below the knee (and thankfully we don't use that gawdawful 1980s turf anymore), the leg just gives. You have to pretty much nail the kneecap when the foot is planted while the opposite leg is still trailing. It's at that precise moment where all the weight is on the knee that it's locked in place and the other leg isn't out in front to protect it. And this is all assuming your man tries to run right through the block, which generally only happens by not knowing you're there. Otherwise, you can dive at someone's knees a thousand times and only give them bruised kneecaps.

I've seen knees taken out with low hits, but it's when the guy doesn't see it coming so he doesn't jump or adjust his stride in any way. The body has some pretty evolved reflexes, and it only takes the slightest weight transfer to avoid a knee injury. Again, the ONLY thing you need to avoid ruining a knee with a hit is to get your weight off it, and the body can do that very quickly. The knee can also be damaged by a second blow (first blow locks it, second blow shears it) or someone rolling on it, but welcome to football.

Most knee injuries are caused by voluntarily locking it. We have reflexes to protect the knee from blows, but we haven't evolved kevlar ligaments to handle athletes with 100 pounds of fast-twitch muscle pivoting at full speed.

Again, I have no data, but methinks cut blocks are the pitbulls of football -- not relatively dangerous, but they're ugly and when they actually do harm the results are visually spectacular. A concussion has far worse implications for a football player's future quality of life, but no one really gives a crap because it's just a guy "getting his bell rung". Knees can be repaired, but a blown knee can get an entire stadium cringing and we can't have that.

September 6th, 2012 at 1:06 PM ^

September 5th, 2012 at 4:05 PM ^

Can anyone give an insight into the history of this type of offense as it relates to the other old school option style offenses?

Fritz Crislers single wing > Winged T>Wishbone>????

I'm just curious about the orgins of the many derivatives of these type of schemes.

September 6th, 2012 at 1:41 AM ^

September 5th, 2012 at 6:46 PM ^

I know that the service academies play "small" guys because they literally can't have guys be bigger and still scrape through the military requirements (especially endurance stuff), but I've always had a fondness for the resulting normal-sized-people-playing-football. Army-Navy is consistently one of the most watchable games of the year not involving powerhouses. (Uh, also my dad was in the Navy. That might have something to do with this opinion, especially recently.)

I also have a suspicion that the gradual size creep is probably causing corresponding gradual a) direct injury creep and b) residual health problem creep, especially for linemen.

I know the Shaun Rogers and Ndamukong Suhs of the world are way more "in shape" than I am, but carrying that kind of weight has to be unhealthy. Nothing would make me happier than to see football leagues - NCAA and pro both - instituting some kind of "healthy body" standards.

The only drawback I can see would be the loss of the Fat Guy Touchdown, and while that's a major drawback, everything has its price.

September 5th, 2012 at 7:41 PM ^

The Fat Guy Touchdown is a sacred American institution

Comments