Neck Sharpies: Belly and the Well-Fed Spread

I challenge anyone to find a greater irony in football than the fact that the spread 'n shred offense was rejected at Michigan by Rich Rodriguez and restored under Jim Harbaugh. Rich Rod scrapped it in 2010 because Denard wasn't good at option reads. Hoke avoided it because he had other plans. Harbaugh is on everybody's short list of best coaches in the country for Hoke's plans.

But here we are, running not just zone reads and split zone as a check, but the checks to the checks. Last week I got into the arc keeper, a counter off split zone that can hit for big yardage. But Michigan was also making heavy use of "Belly", a Rodriguez favorite from 2008-'09 that looks like a zone read but is actually doubling the backside DT and planning for the cutback. And it did its job.

Let's break out our 10-year-old playbooks and see how it works.

The Standard Defense of Zone Read

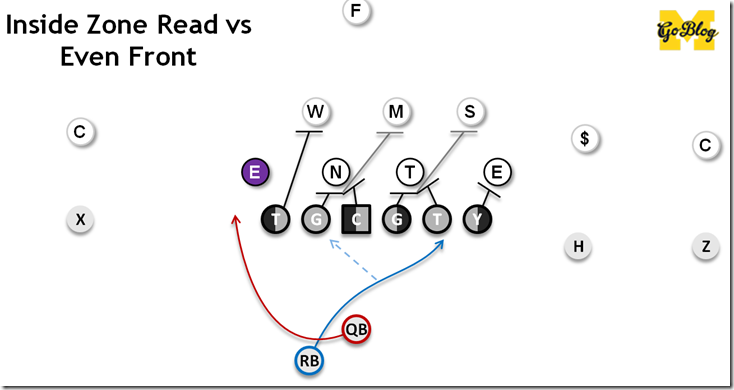

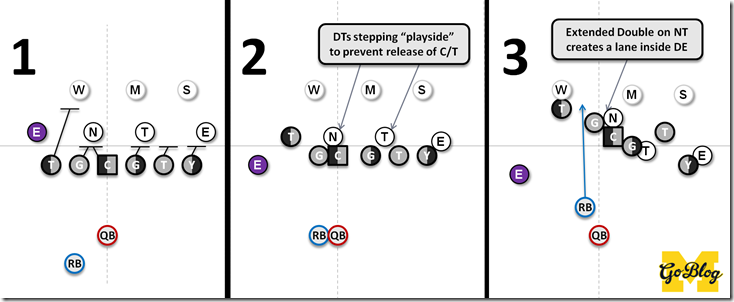

Since this is really a counter to a base play it's best to first understand the base play: the Zone Read option. You're familiar with zone read, but probably more so with the option part. For this exercise you need to pay more attention to how it's blocked.

After the backside end is dealt with by the option, the play becomes, well, whatever off-tackle run play you want to use. You can run inside zone, outside zone, even Power-O or Down G with it. In the above example it's inside zone, and when running the zone read game out of a pistol formation this is by far the most common run play.

[After THE JUMP: gliding downhill]

Zone running rules are simple: 1) Get the linemen blocked, 2) Get your extra material to the linebackers. 3) Seal or run off the defenders to create running lanes. Let's go left to right with their thought processes versus this (base 4-3 over) front:

- Left tackle: Release to the WLB.

- Left guard: Get this NT blocked with help from my Center so we can get one of us to the LB level

- Center: Help the LG get this NT blocked so I can get to the LB level

- Right guard: Get this DT blocked with help from my RT if necessary so he can get to a linebacker

- Right tackle: Make sure my RG has this DT blocked so I can get to the LB and create a crease.

- Tight end (Y): Kick out this LB so there's a nice big lane to run out.

- Running Back: Find the gap that forms, starting with off-tackle then work back to a cutback lane.

Often in the course of running inside zone read, the quarterback has to take some time to make his read while the defense is reacting to the blocking. By the time the running back has the ball every defender is doing a fair job of closing every frontside gap and forcing a cutback towards that unblocked end:

Many a good inside zone read has died this particular death. The linebackers react too quickly for blockers to get down to them, and the linemen are intent on not letting your guys release, and your poor zone read run is now left to burrow into an unblocked LB's gap or cut back into the space between the unblocked end and the backside tackle.

But what if that was the plan all along?

Belly

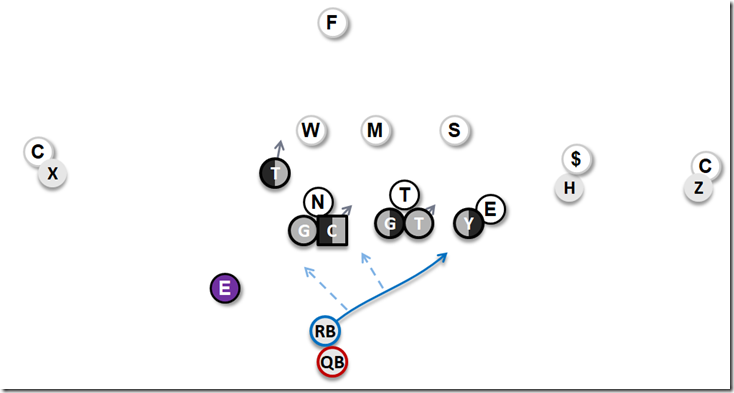

Belly as we define it here* is a zone read play occasionally called "Double Dive" or "Read Dive" that attacks the cutback lane without ever having to cut back to it, giving the RB a direct shot at the backside while it's still pried open by the DE being optioned, and prying it open further by blowing the backside DT down. On a handoff all the back has to do is shoot straight ahead into the gap between the option and the ass-kicking.

For the first second after the snap, Belly moves like an inside zone read: The quarterback and running back get a mesh on, the tight end is kicking, the RT is threatening the next level, the RG is trying to get around the frontside DT, and the backside guard and tackle appear to be combo'ing the backside DT.

Except they're not getting off that NT. In fact they're moving him quite a bit. In fact there's starting to be a lot of space on that backside there. In fact: oh crap!

By the time that tackle realizes this double isn't some temporary nuisance en route to the second level but a planned thing to move him off the line of scrimmage, it's too late to do much about it. That's the whole point of a designed cutback: You want the defense to react to the direction inside zone attacks, so when the play cuts back they're caught on the wrong side of it.

* [As with many football terms this one gets used to mean different things. We got it from Rich Rod's WVU playbook, and that probably misappropriated a Wing-T play that's similar to Down-G.]

Belly in Action

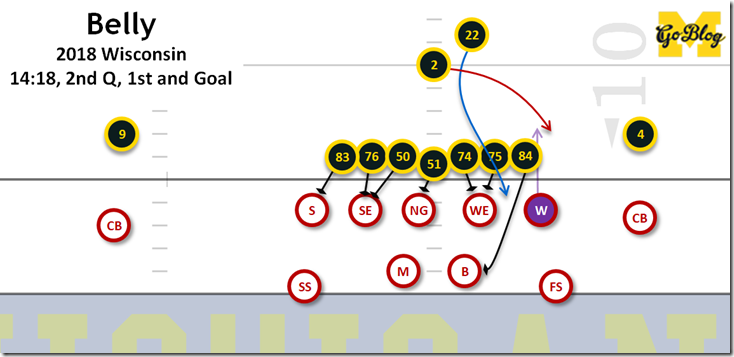

Here's an pair of examples from the Wisconsin game. In fact they're the two plays directly after the 81-yard run I drew up last week. That too had a little belly action, i.e. they were doubling the backside DT.

The way I draw my play graphics makes it hard to tell how far the whole mass of bodies shifts. Note while you watch that the running back is going straight down the hashmark. It's not a cut; this play goes straight through the liver.

Play 1:

One thing to note from the above is the Pistol formation. If you have a super electric running back and run a lot of outside zone with your zone read (like Rich Rod) you can get away with a pure shotgun formation, but time is of the essence and the RB's downhill action from a pistol set can make all the difference when trying to run by the optioned guy.

Another thing is Wisconsin's in an odd (3-4 or 4-3 under) front, but the same rules apply: Wisconsin's "weakside end" is a defensive tackle in all but name. By adding a tight end to the backside the offense can still get that free release on the linebacker behind the guy they're doubling. Some teams also do it with a lead blocker.

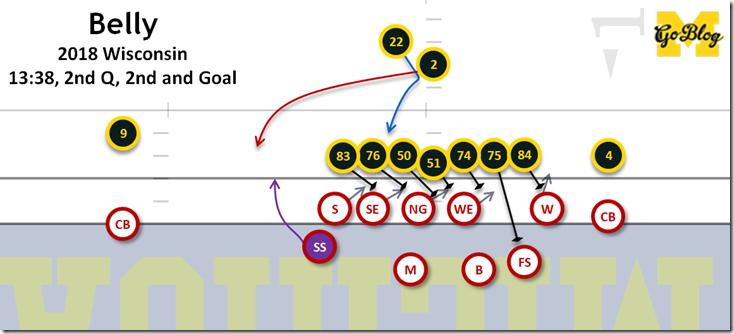

Play 2:

An obvious question with any zone run is what do you do about a slant. If they slant away from the playside the last blocker has block the last unoptioned guy since you can't take his buddies off the double on the DT. This should bring a linebacker (or in this case a safety) around to be optioned.

This one caught a slant but the blockers are all on their toes and pick it up, even Gentry, who had the hardest job. It's hard to represent on the drawing but Wisconsin's line slanted so far that Higdon wound up barreling straight down the hash mark they started at and Bushell-Beatty planted the "SE" two yards inside of it.

The "ZONE" of the zone read also comes into play. According to Rodriguez this wasn't referring to the blocking but the area the QB reads for a defender to option. The difference between reading a player and whoever's in that zone becomes apparent when the defensive line slants. The SAM (#17 Van Ginkel) was the end man on the line of scrimmage when they lined up, but when it came time to read it was the strong safety holding the edge. That safety made the read hard, and Patterson countered by riding the mesh point almost all the way to a shared TD. By the time Higdon has the ball to himself the safety has shuffled down to meet him but there's no way a safety is stopping a Higdon.

I know we all bemoaned the lack of Bench Mason when Michigan got down to the 4 and 2 yard lines, but this play really gets the job done. The extra defender who has to commit to Patterson's legs can't be shooting in without a blocker, and the dive-ness of the backside handoff hits downhill and quickly like a good short gainer should.

The Harbaughification of Belly

I mentioned earlier you don't have to run this with a simple spread zone read look. In fact against Michigan State, the Wolverine offense added all sorts of blockers to the concept.

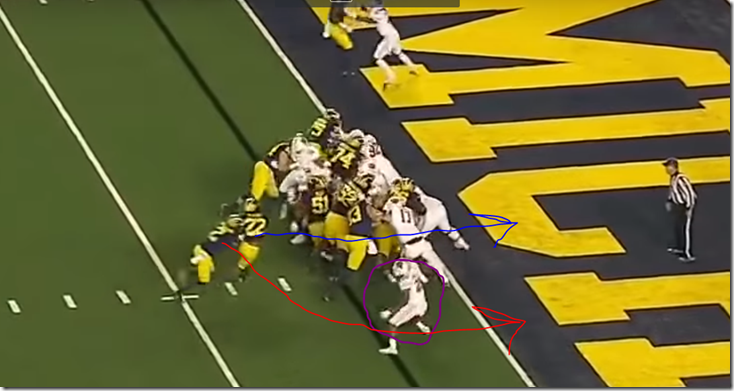

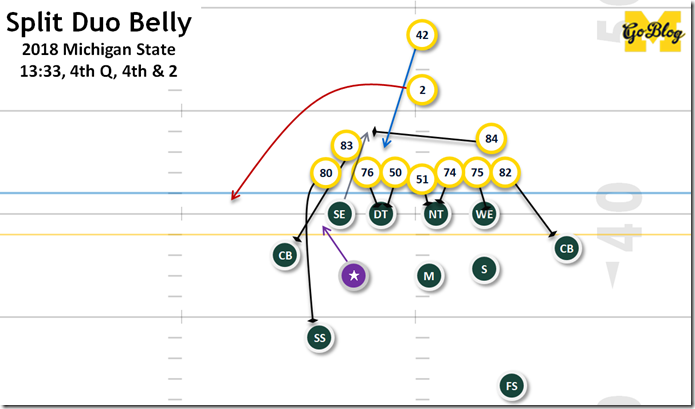

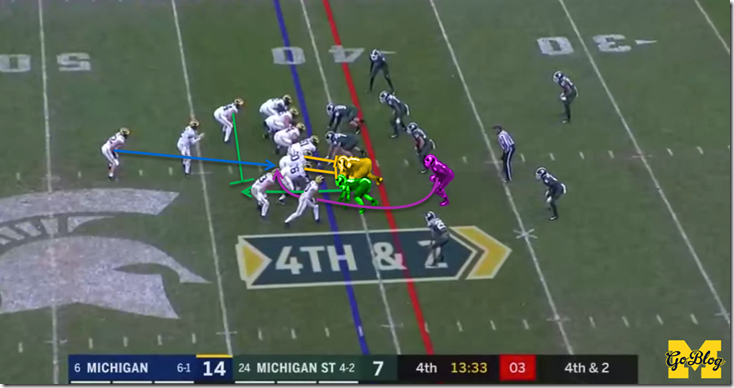

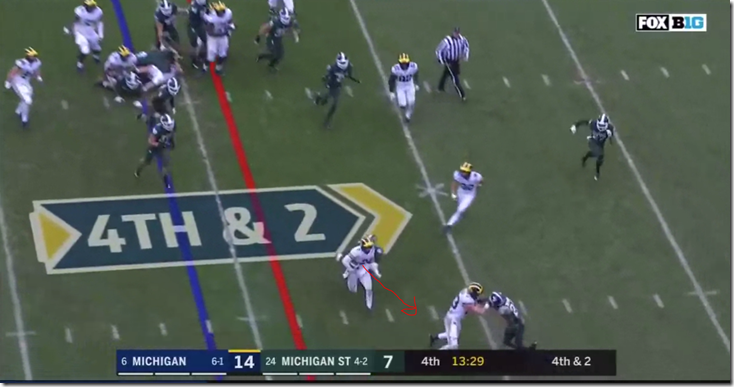

Here's a critical 4th and 2 early in the 4th quarter. It's a mark of how much Michigan trusts their belly game that this is their go-to short yardage play in such a situation.

Mason is indeed out there as the tailback (though back when the Flexbone was all the rage that guy was called the fullback). But this ain't no "We're diving the fullback—try to stop it" play. Okay, it is, but there's also a zone read, and now you really get to see what we mean when we say this spread 'n shred concept makes the defense play 11-on-11.

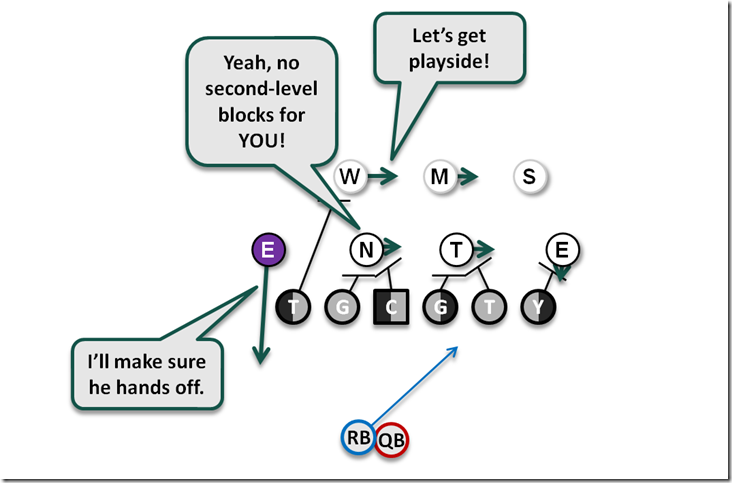

The play is blocked like it's meant to be a split zone duo. Duo is an inside zone play with extended doubles on both DTs. Split zone is that zone read counter where the guy who thinks he's being optioned suddenly discovers he's getting kicked with a fullback/TE/H-back coming opposite the flow of the play and the RB, who was always getting the ball, scoots through the resulting gap.

If it was Split Zone Duo, Michigan State has this solved:

The cornerback and strong safety on that side have to deal with Martin and Gentry in coverage so they're out. Michigan's doubling the DT (yellow), letting the DE (green) upfield to be kicked by McKeon, and bringing Mason on a dive. Sparty's plan is to hammer down the MLB (Joe Bachie) so Onwenu has to come off the double on the DT (Raequan Williams) who should be able to handle a single-block without giving up room. To cover the edge they will gap exchange: the DE (Willekes) is going to crash inside, thus putting his confrontation with McKeon right in the way of a dive. Willekes is replaced by the "Star" linebacker (Andrew Dowell).

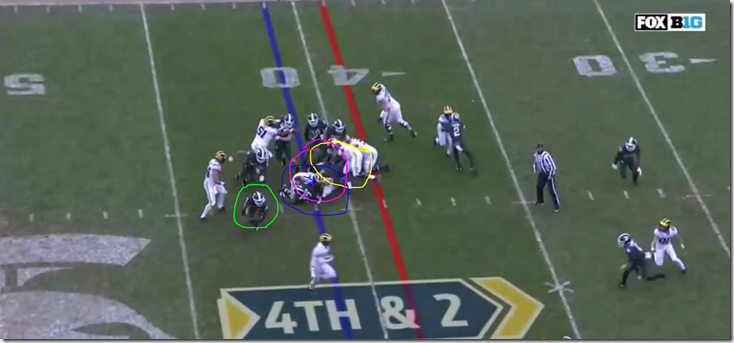

I just named all four guys I starred on the MSU FFFF diagram. They're all selling out against a split zone, the exchange giving MSU equal numbers against a handoff while saving a safety. The result is a mass of bodies at the point of attack and a dead play because—if we're looking at split zone—the quarterback is just a guy delivering the ball then watching the play. Except he isn't. He's….

Ahem…

YO, CAMERAMAN! Pan down, man!

Hahahahahahahahahahahaahahah!

Lessons:

1. See the four star players of Michigan State's defense?

Point at them.

HAhahahahahahahahahhahahahahahahahahahahahaahaha!

2. Michigan State should have defended this better

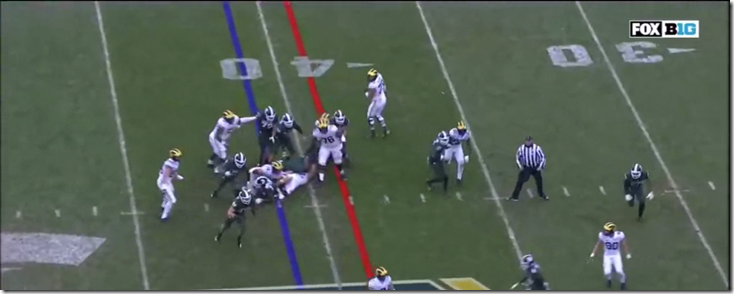

Very true, and the guy to blame is Andrew Dowell, the optioned guy, who sold out 100% on the FB dive, leaving Patterson an easy read and a wide open edge. It's possible he thought Willekes, being outside of that crack block and all, should have been set up to contain and force a handoff. But no: when you crack/replace the guy who cracked is the guy inside and the replacement has the outside. Willekes shouldn't be expected to reverse his momentum into a guy, turn around and chase a quarterback with good legs who started facing the opposite direction. If Dowell set up outside and forced the give the blitzing linebackers created enough of a jam to have a shot at stopping even Ben Mason, and certainly not giving up more than two.

That's relevant to us because opponents are still playing the early season tendency—which in fairness to them resurfaced on that unbalanced arc zone read that Patterson wishes he had back. They also might believe pushing all their chips in against a full Ben Mason is the only way to win this play. Having an offense that forces the opponent to do unsound things that make them risk looking stupid is part of having a good offense.

3. This is a good play

Compared to other short yardage options, this one might be a little more susceptible to getting entirely blown up, but it's also likelier to have a high success rate because the quarterback cancels out a front seven defender. Even with the LB blitz, if Dowell plays this right it's Ben Mason going down hill behind Juwann Bushell-Beatty, who did in fact win his battle with Williams.

While any play can break big, operating so closely to an unblocked guy and leaving linebackers unaccounted for tends to lead to modest gains. Michigan isn't marching down the field with Belly. They can use it as a tough to stop 3rd/4th & 2 option, and bust it out some more when they're running their regular zone read option game to keep the defense from overplaying the frontside or overcommitting to defending split zone and arc zone.

4. It's zone—you can change gaps still

Often—especially when the defense shifts to an odd front—when running Belly the original running lane gets jammed up. Like Duo, while the play design calls for extended doubles, it can easily become an inside zone if the defense plays it irresponsibly. Cutback gaps can and do form.

5. Belly may be Rodriguezian but it's also very Harbaugh

Doubling a DT with Juwann Bushell-Beatty and Michael Onwenu. Straight downhill runs. Opportunities for all sorts of crazy blocking angles. I'm sure Bo would approve.

October 24th, 2018 at 6:14 PM ^

I like it.

October 24th, 2018 at 11:20 PM ^

-1 for Aaron Rodgers and his stupid face.

October 24th, 2018 at 6:19 PM ^

This is so great. I do love the SRK diaries, but your neck sharpies are much more detailed and informative.

A point worth making is that both Shea and Higdon are doing exceptional jobs at selling the hand-off when Shea keeps. Higdon's height and propensity to get low and sometimes spin makes it near impossible for defenders to see if he has the ball.

Love this series.

October 24th, 2018 at 6:42 PM ^

There truly is nothing new under the sun.

Anyone who wants a great education on all of the blocking schemes and terminology that are at the root of all of this can google “Olivet wing T playbook”, download the pdf & enjoy.

October 24th, 2018 at 8:17 PM ^

Great post! Thank you - really explains what is occurring and clearing up a few things.

1. The morphing of terminology - belly runs usually meant a FB from an old T style formation going up between the guards.

2. Countering the counter - it is a trite saying but I'm going with it - a chess game between the offensive and defensive coordinators - trying to trap each other into making logical reasonable choices that are ultimately wrong.

3. Why we didn't see this action when we had Denard Robinson with Rich Rod.

October 24th, 2018 at 8:33 PM ^

To Q3, maybe had RichRod hired Don Brown and stayed to coach Denard for another year. I don’t remember if Forcier was better than Denard in option plays.

October 24th, 2018 at 11:22 PM ^

I remember that Tate was way worse than Denard at going to class.

October 24th, 2018 at 11:20 PM ^

One thing I have noticed and appreciated about Harbaugh's Zone Read program vs RR or Urban's.... Protection of the QB. I have not seen Patterson take an unnecessary nasty hit as a regard to a QB run play. I always cringed when Denard would be purposefully run into stacked lines with 300 pound linemen... or bashed repeatedly into LB running full speed down hill. I think that is why Urban's QBs struggle so much to stay healthy and relevant throughout their 4 years, was because he ran them every possible occasion. It was an effective strategy from a results perspective, but seemed like a liability from a career-extending perspective of the QB.

October 25th, 2018 at 1:19 AM ^

This is why college teams should always recruit dual threat QBs. The playbook doubles (hyperbole, but you get the point). Doesn’t matter what type of offense you run, you simply have more options with a QB who can run and pass. Even if his passing ability is mediocre, a dual threat QB can get a team to the playoffs more easily than a pure pocket passer (all else being equal). Too much has to go right for a team with just a pure pocket passer to be successful, like having an overpowering O-line, and a top ranked defense. The last team like that was 2012 Alabama then Saban went dual threat. By comparison, just look at OSU’s problems this year with a one dimensional QB in Haskins. They can’t convert third downs and score in the red zone like they used to with Barrett and Miller. More than the coaching, more than Warinner, this Michigan team is better because defenses have to play a dual threat QB. Forget pro-style QBs who can’t move.

October 25th, 2018 at 9:38 AM ^

The "all else being equal" is the qualifier that makes your argument, though. I mean, you're not wrong, but you're right specifically because of that. You can justify recruiting a pocket passer if things aren't equal. If you find a Drew Brees type who can read coverage like a teleprompter and hit a cereal box shot out of a catapult at 30 yards with a berserker in his face, you recruit the guy even if he's in a friggin' wheelchair because he can make all those things go right. The upside makes up for the downside. But to your point, these guys were never common to begin with and increasingly difficult to find, whereas raw athletes grow on trees. That said, there are running QBs who aren't dual threats because they can't throw -- the B1G has a lot of QBs who get opposing safeties to sell out against the run because they don't threaten with their arms at all.

Yeah, if you've met two mediocre passers and one can run while the other can't, you recruit the guy with better legs, but I think that was always the case.

October 26th, 2018 at 12:11 AM ^

I don't think I totally understand what you're saying but I don't necessarily disagree either. You seem to make sense. My point is that if you have two teams that are equal in every way, offense and defense, except for the QB position, the team with the true dual-threat is more likely to succeed in college than the one with a pure pocket passer. As an example, I would argue that the only real difference between MI and OSU in 2016 was JT Barrett's ability to run. Admittedly, a lot of bullshit went against MI that game, but MI still outplayed them for the vast majority of it. Barrett's running is what kept OSU in it. Even a mediocre MI team led by Devin Gardner put up 42 on a great OSU defense because Devin could move the chains with his feet.

Take Denard and Brandon Peters. Each was a 4* star out of high school, but one could run better than he could pass and the other could pass better than he could run. I would say they are directly inversely proportional in terms of their comparative running and passing ability. My point is ALWAYS recruit Denard first. Too many other things have to go right to be successful with a Brandon Peters type QB. That's why even college teams with far lesser talent running a spread option with a dual-threat QB can still put up 35 points against a top 10 D1 team. Unless you're 2012 Alabama, you don't give yourself enough of a chance to win with just a pure pocket passer--so don't focus on recruiting one. Try to get the best dual-threat QB out there every year. I don't understand why any college team would not want a dual-threat QB, especially a TRUE dual-threat--one who can pass well and run well. Now he's the unicorn.

October 25th, 2018 at 7:56 AM ^

Fantastic breakdown! However, as I'm reading it, this just looks like a variation on the inside zone/zone read play to me. I don't know that I could rightfully call it belly. Belly is a staple of the Wing-T offense which has the core principal of involving a block down, a block out, and a block through at the point of attack. Without a wing/H leading through at the point of attack on a LB, It's just not belly to me.

October 25th, 2018 at 9:48 AM ^

I'd concede your point, but Jim MF'ing Harbaugh doesn't. On his podcast Tuesday, he called them belly plays. Yes - he talked about the same plays Seth drew up. Just saying...

October 25th, 2018 at 7:56 AM ^

I’m confused, so i think this is a typo:

“Harbaugh is on everybody's short list of best coaches in the country for Hoke's plans.”

October 25th, 2018 at 9:24 AM ^

The way I understood it was "Harbaugh is good at coaching the style that Hoke wanted to do."

October 25th, 2018 at 9:49 AM ^

More awesome stuff, Seth! Thanks - I really like learning about football with this series!

October 25th, 2018 at 10:28 AM ^

Using that logic,(every college team should have a running QB) every HS team should run a T offense. 3 things can happen when you pass and 2 of them are bad.

October 25th, 2018 at 3:50 PM ^

On the 4th and 2 vs. MSU, it looks like Patterson's knee almost hits the ground similar to Trace McSorley's slip the week before.

Comments