Neck Sharpies: Oh I'm Sorry Were You Keying That?

Nebraska fixed their atrocious linebackers by giving them aggressive reads. So Michigan unfixed them. [photo: Eric Upchurch]

I had a very hard time pulling anything interesting from this game. I wanted to see Michigan dominating with skill, speed, and play design, but the takeaway after a rewatch was Nebraska's linebackers were responsible for much of the Michigan offense's explosive day.

This was something of a surprise. In the film preview I thought the Huskers had found a good player in WLB Mohamed Barry (#7) and a serviceable one in MLB Dedrick Young (#5) by giving them easy Keys and telling them to play those aggressively. I think Michigan saw this too, and also a way to use that to make Nebraska's linebackers atrocious again.

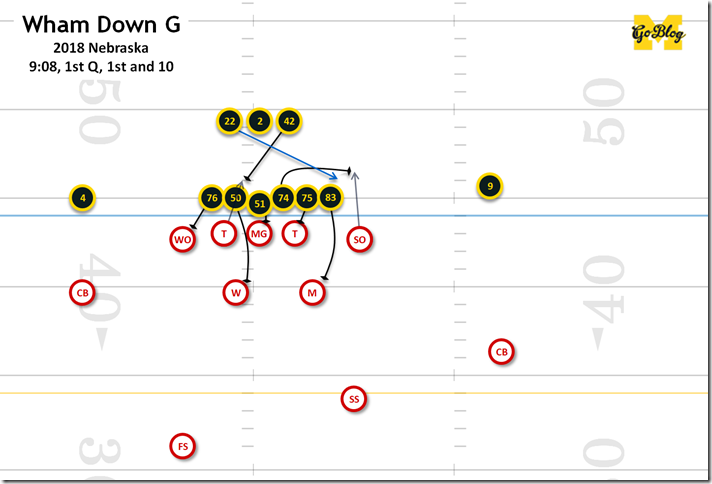

So the play in question is the first snap of Michigan's second drive. They had already used it for a big Higdon run on the first drive but Nebraska did some funny stuff that time while this was straight-up pwnage.

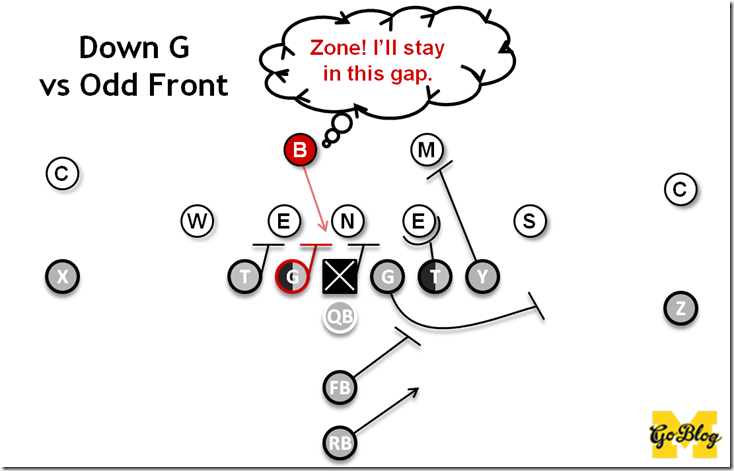

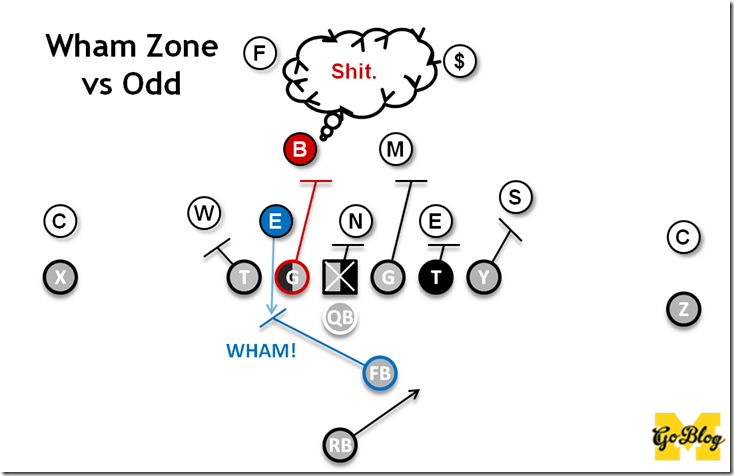

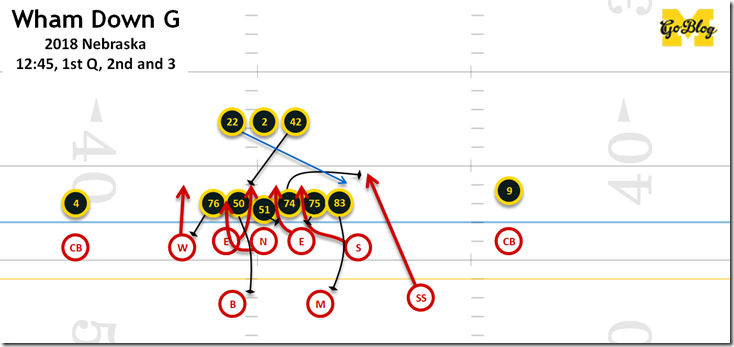

Michigan is running two concepts on this play to screw with the Nebraska LBs' Keys. On the frontside it's Down G, and on the backside it's a Wham Block. Let's go over the bolded terms.

About Keys

One of the great things about about Down G is how it messes with "Keys." Keys are cheats that defenses use to get extra defenders to the ball faster by identifying what the play is by certain types of backfield action. Every defense uses keys, and the game that running game coordinators are often playing is identifying what the defense's keys are then using that against them. The defense meanwhile will have different keys for different looks to punish an offense that just sticks to the plays they run well.

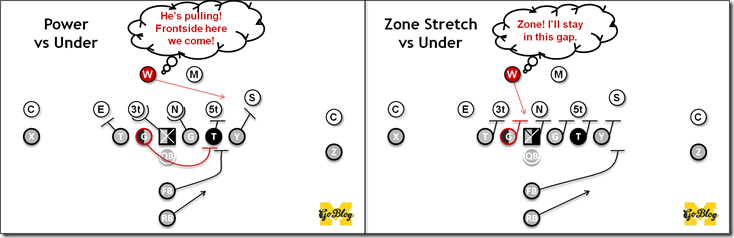

A highly common Key against power teams is to read your guard. The backside LB ("W" in the diagrams below) is often Keying the backside guard to decide what to do. If the guard pulls, that LB can guess the ball's going that way too and hightail it across the formation, arriving in the intended gap before the pulling guard and mucking everything up.

If that backside LB reads a zone block he doesn't activate so quickly, since he's got to cover that lane in case of a cutback. For completeness if the guard steps back to pass block, the LB knows to sink into coverage, or if the guard releases the LB knows to get playside and dodge the block.

Keying is a slider; you can use it as information while staying on your assignments, or tell your players to go hell for leather whenever they read one. Where you set that has to do with what your players are capable of doing on their own. If you have a particularly fast linebacker or one who can diagnose more things on his own, you don't have to try to cheat him into the right spot so much. Think back to 2011 Michigan with Brandin Hawthorne, who could knife through for some key stops or get caught paralyzed, versus Desmond Morgan, who though a true freshman was more diagnostic and decisive in his approach.

Nebraska is at the Hawthorne stage of a similarly wholesale rebuild. They're not as blitzball as the WMU and SMU linebackers when they Key run action, but they're up there with recent Rutgers and Minnesota teams Michigan's faced who don't wait to see the whites of their blockers' eyes before firing at a gap. As you may have derived from those memories, playing blitzball against a Harbaugh run game can get you a few stuffs followed by a good view of the back of Higdon's jersey. Except with the Huskers, it was a different shiny thing.

[After THE JUMP: Michigan's getting good at this, Nebraska was REALLY bad]

About Down G

Down G, the concept I wrote about after Michigan used it to pulverize WMU, is a counter play to a common key against Power teams. If you don't want to read that whole thing again, Down G pulls the frontside guard to kick the edge, and blocks down on the rest of the frontside defenders like a power play, but plays zone on the backside of the play. What makes it a counter is it's messing with the backside guard's key (B" in the diagram above for the 3-4 term "Backer"). The linebacker is reading zone when there's a power gap happening on the other side.

By the time he reacts it might be too late: the fullback could be through the line to pick him off, the running back could already be beyond him, or one of the other blocks on the frontside might have created a wall that this unblocked guy can't get around. Speed to the ball is the ballgame. One second wasted reacting to a lying key and the whole world might have changed.

Since Michigan's been running Down G for big gains the first quarter of the season, Nebraska was well-advised to change up the linebackers' keys.

About Wham Blocks

A wham block is a trick that teams with extra running backs in the backfield use to get a block on a lineman without using a lineman. I wrote about it in 2016 after Iowa used them too effectively against Michigan.

You can't do this all the time of course but in this day and age when linemen treat not being blocked as being optioned you can get a really good ol' fashioned fullback thwack on a guy.

The advantage of this should be quite apparent. You just took out one of their 300-pounders with your~240-pound linebacker, and you get to spend those ~60 extra pounds by immediately releasing your 300-pound lineman on a 240-pound linebacker.

Now imagine your lineman is #DIV/0! pounds and their linebacker is a modern barely 230 former safety-type who's standing flat-footed because he's reading the wrong key.

About this Play

Watching the game I'm pretty sure Nebraska's plan against Michigan's two-back formations was to have the linebackers read the fullback instead of their guards. That makes sense given what Michigan had put on film so far. Ben Mason is a true sophomore who was mostly buried last year behind two seniors. This year he has mostly run directly at the gap and hit the first thing in the wrong shirt.

Take this Down G from the WMU game:

This was WMU adjusting to the play that was killing them. The edge OLB, #57, dove inside Bredeson's block to blow up the play, and Mason still ran head-first into the intended gap while Bredeson tried to kick out the guy who wasn't actually the kickout guy (that's the overhang S who crept down). Nebraska played it that way on Michigan's first drive and got the same blocking: Bredeson didn't redirect, Mason plowed forth.

The scout on Michigan 2018, then, was don't watch the backside guard: he's a liar who Down G lies. Rather, watch the 19-year-old fullback constantly throwing himself into the gap the running back is taking. And if this was expected to be another SMU I bet Harbaugh comes out in an I form and burns a down to establish the key. Since he thought Scott Frost would give him a game, Harbaugh came ready for the counter to the counter with a counter to that. Second play from scrimmage:

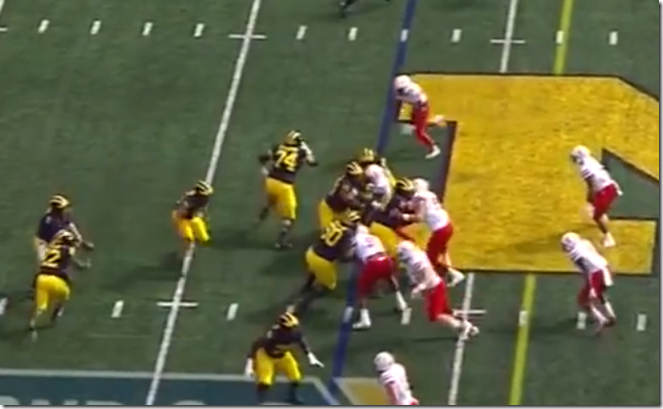

Nebraska's running an exotic here with their front. The nose and backside DE are twisting and the frontside is slanting with a safety blitz added as contain, giving the defense an extra guy inside against the run. It should be a Rock/Paper/Scissors victory for Nebraska DC Erik Chinander. Not only did he buy an extra unblocked defender for this play but he prevented Michigan from getting anybody to the second level:

Onwenu can't release because the DE he was supposed to leave for Mason to Wham is instead twisting right into Onwenu's path. Ruiz sees the nose disappear to the backside and looks for work, catching the slanting frontside DE. Runyan has to pick up the SAM who darted in. Gentry also has his release delayed by that guy slanting across his path. By the time that's happened Gentry has no idea what to do and just helps seal the guy who's already sealed himself. So Nebraska has four Michigan blockers tied up with their three interior guys, and an extra run defender, freeing up BOTH linebackers to flow to the ball unimpeded. If this is Wisconsin it's a play going nowhere. It's not Wisconsin.

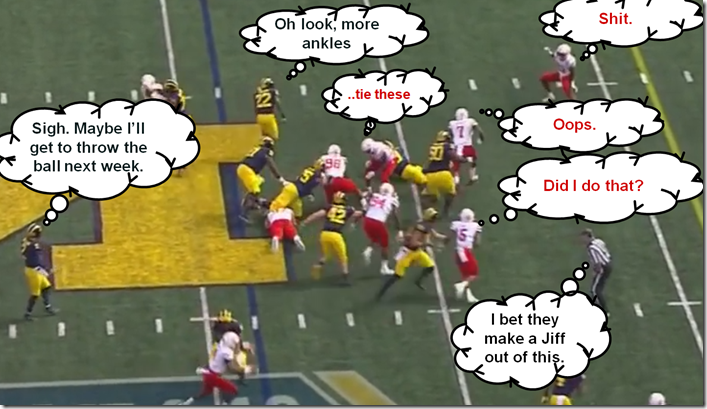

Watch the two inside linebackers here. One has both feet just outside the hash marks, the other has his inside foot on the bottom of the midfield 'M'.

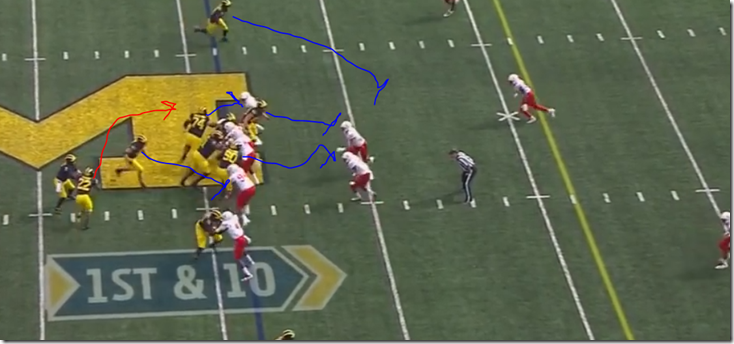

Coming up to the mesh point the MLB (#5) steps wide with Bredeson's Down G pull and the WLB (#7) leans that way. They're now both a bit playside: #5 is in the middle of the M's serif and #7 is on the hash. If they diagnose the play and attack it's over. What are they looking at?

Let's hand off and see if they continue to head in the correct direction? Uh…nope.

It looks like #5 was keying on Bredeson. He's alone in the gap since Gentry didn't bother to try to block him. But the guy's answer to this, rather than running into the lane that's all his, is to really wide, like not even on the serif anymore.

And #7 wasn't keying the guard. He had his eyes on Mason. Mason was going backside for a Wham block. It's not the DE who was there initially but the nose who replaced him. Doesn't matter to Mason, but the linebacker here is so Keyed on Mason that the idea of a Wham block hasn't entered his mind. He cuts back to reestablish the backside gap. And then…

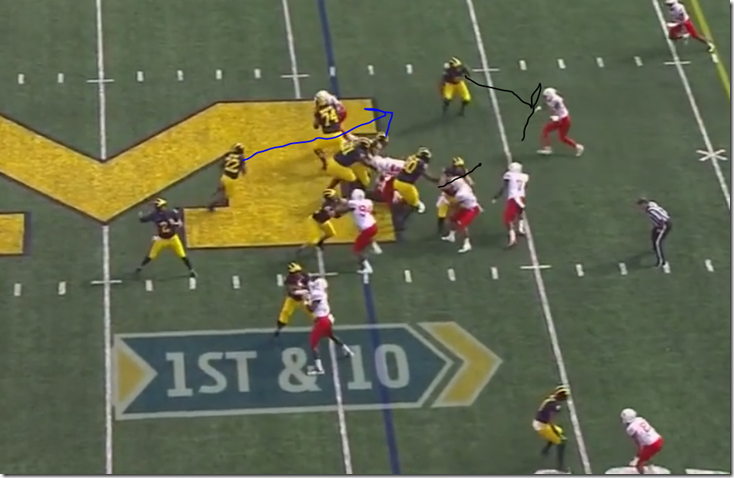

Too late. The MLB is now half-way up the M with a ton of space to either side of him. He's also flat-footed. A TFL is out of the question, stopping the first down is out of the question, and reversing his momentum in time to at least funnel back inside is really the only thing left he can do. Meanwhile the WLB right back where he started on the hash mark, moving laterally, and Gentry has finally popped off and come down to seal inside. Higdon gives a fake cut outside to keep the MLB frozen on the M, then dashes inside of him as Gentry seals.

And just like that:

He's gone. A safety gets added to Karan's kill count, and MLB #5 finally chases out of bounds within Ben Masonball range of the end zone.

Run It Again

Fast forward to the first play of the next drive. Charles Woodson and Lloyd Carr are just leaving the field after a standing ovation that was only mostly for the recently inducted Heisman winner and College Football Hall of Famer. Let's see if Nebraska's linebackers have learned anything:

Uhhh…nope. Watch these same guys reacting to Ben Mason.

Quick rule of thumb: Unless they're both unblocked in the RB's face you never want to see both of your linebackers squeeze together like this at the snap. It means at least one of them is not reacting correctly to the run action in front of them. It also means the incorrect one is going to end up blocking his buddy a bit.

Doink. The replay angle was bad because nobody on this production team knows anything about football but you can see the MLB (LB who starts in the upper-right) vastly overreacting to the fullback.

Gentry takes out the MLB. The WLB has to work his way around that block while Higdon makes his cut.

With the cornerback playing so far off Michigan added a crack from DPJ to take out the safety Karan decleated on the last one. That crack occurs, and the guy loses his shoe again, and when he stands up his first thought is he'd better tie them.

Then Higdon outruns everybody down the sideline and it's 14-0. Nebraska pulled #5 for the next drive, replacing him with #3 Will Honas, a JuCo I thought was a major downgrade when he played against Colorado. At least this time he knew what to do:

This time Nebraska twisted, which again prevented blockers from releasing to the OL level and this time the NG got a little chip on Ruiz to prevent him from sealing the looping DE, who'll become relevant as Ruiz has to zone block him all the way through the gap. The new MLB however made the play by stepping into the gap when he saw Bredeson pull. WLB #7 again hung out backside for the fullback but was more ready to spring frontside. Michigan finally had to move on to the rest of the script.

The Rest of the Script

I think Harbaugh got through just half of his opening script before shelving it for a more worthy opponent. The only other wrinkle from their Down G game was a play the next drive where they convert kickout block from Bredeson to a true crack-replace pull:

They also debuted a run-screen option version with it:

And ran it from a pistol with a TE to either side so there's no fullback to read:

Again, one of the LBs just had to get into his gap and make a tackle. Again, Higdon wasn't even slowed. Nebraska linebackers: bad at football.

The staff probably expected to get Nebraska with the fullback action once, not get 90 yards running it twice. No team in the history of football can "prepare" for the opposing middle linebacker to walk himself out of a play then get so mesmerized by the same play two snaps later that he bonks into his fellow ILB. Michigan probably came in thinking they would futz with the linebackers a bit to get them to stop trying to cheat toward things they see in the backfield. While you can't expect opponents with decent linebackers (e.g. Northwestern) to completely short-circuit, convincing LBs to be more cautious about reacting to their Keys is certainly translatable, and also paid off in this game:

watch #7 , the WLB just to the right of the hash mark

Michigan happily futzed with their fullback reading the rest of the day.

What We've Learned:

While Down G is a counter play (you see how it can be beat schematically if your LBs aren't busting everything), Michigan was able to once again use it as a highly successful base running play, identifying the Keys that defensive coordinators meant to use against it and taking advantage of that. I don't think it's going to work nearly as well against Northwestern, whose best player is a 4-3 strongside end who can probably win most snaps against a Michigan OT or tight end block, and whose next best player is heady old fashioned linebacker Paddy Fisher.

It's still nice to have that wham block version out there so future opponents won't be so quick to key Mason—that's pretty crucial for maintaining his viability as a regular lead blocker. There's more to explore off this play, using Bredeson as an arc blocker, throwing a slant off play-action, and running a fullback dive off the backside.

Also nice: Karan Higdon is VERY good at running this play. Twice Nebraska had this dead to rights by their playcall, and bad linebacking aside, Higdon's cuts were able to turn that space into big yards. The more they rep this, the better Michigan is getting at responding well to the curveballs defenses send at it, and that's already paying off.

September 26th, 2018 at 12:26 PM ^

Fantastic read; thanks so much for all your analysis & insight!

September 26th, 2018 at 2:00 PM ^

Read your guard.

Signed,

ReadYourGuard

September 26th, 2018 at 3:43 PM ^

Cosign.

Comments