Hockey Nuts and Bolts Part 2: Forechecks

Learning Hockey, a Summer Series: Previously College Hockey 101, Nuts and Bolts 1: Transition Play

Last time we took a look a transition play, zone exits, regroups/counters, and then zone entries. Today we're going to examine a different part of the game, what happens when you're in the neutral/offensive zones and you don't have the puck, also known as a forecheck. Forechecks are integral to a team's system and are drilled down in practice by coaches. They are some of the most structured parts of how a hockey team plays and thus can be the easiest to analyze in this sort of format.

In the simplest terms, forechecks are what teams use to get the puck back in the neutral or offensive zone. Their goal is to obstruct the opposition moving up the ice (in the OZ, a forecheck aims to stop a zone exit; in the NZ, a forecheck aims to stop a zone entry) and then force a turnover. A team's forecheck is part of the bread and butter of that team's system and can define the way they play and the kinds of games they get involved in. Forechecks differ in where on the ice they're applied and also in how they're applied, specifically as to what amount of pressure they put on the opponent. We will go through both dimensions and talk about common examples.

Offensive Zone Forechecks

This is applied in the offensive zone in a few situations. For example, after the puck is dumped in, a team will shift into an offensive zone forecheck as it goes to retrieve the puck. Similarly, after a shot is taken and saved, and the defending team now gets it and attempts its zone exit, the other team will go into an offensive zone forecheck to keep the puck in the zone and recover it to extend the offensive possession. When we speak about certain players being "good forecheckers", this is generally what we refer to, their ability to help recover the puck in the offensive zone while playing inside a broader offensive zone forecheck scheme.

An offensive zone forecheck is generally pretty aggressive, with the intent of pressuring the opponent to turn it over, so that either an offensive possession can begin or can be extended. An OZ forecheck has many different forms, and the alignments may be identical in name to some neutral zone forechecks we'll talk about, but what they actually do and how they operate will be quite different. I will walk through some of them and show clips of how they work.

[AFTER THE JUMP: Lots of diagrams and coach-speak]

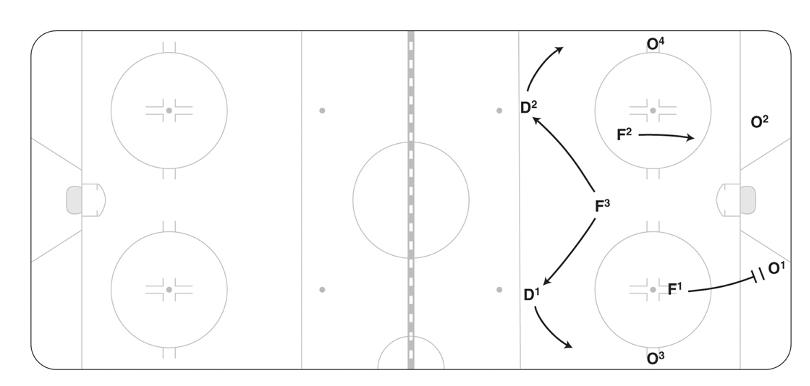

1-2-2 OZ forecheck

In this system, shown in the diagram above from Hockey Plays and Strategies (2018), the first forechecker (known in hockey coaching terms as F1), crashes down to the end boards to flush the puck carrier out to one side or the other. Then the next two forwards (called F2 and F3), are waiting at each side to meet the puck carrier and pressure him/take away passing options, while the defensemen are stationed at the point, ready to pinch and hold the zone. Here's an example of it working to perfection:

Here F1 (CGY10) crashes down hard on the puck-handler (CHI25), makes a good check, and forces a turnover. The loose puck falls right into the waiting hands of F2 on the left wing side, who makes a good pass to F3 (CGY16) in the slot for the easy goal. The strength of this system is that the opposition is enticed to bring the puck up the boards by F1, while F2/F3 take the boards away, creating the pressure. The weakness is that with only one forechecker on the puck-handler, they typically will get more time to think before executing the play (certainly more time on average than in the above clip), and thus a good passing defenseman (of the kind we raved about when discussing zone exits in my last article) can break right through it. The 1-2-2 is not the most aggressive alignment of offensive zone forechecking as a result.

2-1-2 OZ forecheck

This system is a bit more aggressive than the 1-2-2, and it was made famous by the 1980s Edmonton Oilers led by Wayne Gretzky. It's a physical system where F1 and F2 both crash down on the puck-handler, applying a lot of pressure there and the defensemen are ready to pinch hard at both points, completely taking away the outside lanes and forcing the opposition to move through the middle of the ice in the defensive zone, the most dangerous place to turn the puck over. Here it is in action (first clip):

The two Penguins forecheckers overwhelm the puck carrier and create a turnover behind the net, and are quickly able to pounce on it and thread the puck past the goalie. The strength of the system is exactly that: it puts pressure on the opponent and generates turnovers in high danger areas. The weakness of the system is that when you send two forecheckers deep along the boards, and the defensemen are ready to pinch at the point, if the opponent makes a crisp zone exit you are extremely vulnerable to the rush the other way.

2-3 OZ forecheck/"Left Wing Lock"

This forechecking system is another decently high pressure one. F1 slashes down to cut off movement to the right side of the ice, and F2 is then waiting on the other side of the net to continue to push the play to the left. The trick of the system is that F3, the left wing, is ready to "lock" at the far side, to wall it off and hold the play in. The left lane was chosen because the LW is generally the better defensive winger of the two on any given team, but if you have a good defensive RW, you can use them and set it up to lock the right side instead. This press system again is looking to simply keep the puck deep and extend pressure on the opposition, pushing the breakout to one side and then setting up a player to plug it on that side.

The 2-3 Left Wing (or Lane) Lock, and its NZ forecheck derivative that sees the left winger falling back to be in line with the defensemen, was pioneered by the 1990s Detroit Red Wings and Scotty Bowman as a way to continue applying forechecking pressure on the opponent, while still being defensive enough to hang with the trapping opposition of that era (which we will discuss in a moment).

Neutral Zone Forechecks

NZ forechecks, on the other hand, are designed to stop the opposition from moving through the middle of the ice and getting to the offensive zone with possession. When we discussed regroups in our last article, I noted that those are plays designed to slice through the opposition's forecheck. This is the forecheck I was speaking about specifically, a neutral zone forecheck. Teams set these up after an opposing breakout, when the opposition is moving through the neutral zone and they again have objectives and which are NZ forecheck alignment is employed at certain moments depends on situation. Most teams will have a base forecheck they run the majority of the time, but also may use more aggressive configurations when trailing by a goal, and more conservative schemes when up by a goal late in the game. As a general rule, neutral zone forechecks are going to be less aggressive than offensive zone forechecks, because the general goal is to obstruct and slow down the opponent, rather than keep the puck in a zone or force a turnover like it is with offensive zone forechecks. I'll walk you through a few common neutral zone forechecking alignments:

The 1-2-2 NZ Forecheck

This is the most common NZ forecheck employed by teams in the NHL and all levels of hockey broadly, because it's easy to teach and learn. It's also pretty versatile, and you can do a lot of different things with it. F1 ideally pressures the puckhandler and forces the play to the outside, along the wall. F2 and F3 are positioned in outside lanes and are there to meet it, while the two defensemen are waiting back closer to the blue line to help deny entries. The above image shows the 1-2-2 NZ forecheck set up in its most basic form (via The Athletic).

What's great about the 1-2-2 is that you can mold it however you want. It was the basis for the New Jersey Devils' famed neutral zone trap that began a stylistic revolution in hockey, but there's an important thing to clarify: not all 1-2-2 NZ forechecks are "traps" and not all traps are 1-2-2 forechecks. The goal of a neutral zone trap, in simplest terms, is to clog up the neutral zone with bodies and stop the opponent from coming through, forcing them to play dump and chase, and submitting the game to long, frustrating possessions that yield few shots or chances. Neutral zone traps are generally employed by teams facing a deficit of talent, who are trying to bog the game down instead of playing a footrace with the more athletic opponent. Though the Devils made the trap famous, plenty of other NHL teams of that era used it as well (1996 Florida Panthers, late 90s Dallas Stars), to the point that it became extremely common. Michigan Hockey fans may be familiar with Notre Dame using such a style, and NHL fans have grown accustomed to Barry Trotz utilizing it with the New York Islanders.

But again, not all 1-2-2 NZ forechecks are traps. In fact, most in the NHL aren't. Most teams use the 1-2-2 to slow the opponent down, not to grind the game to a halt. And those looking to trap all the time don't always use the 1-2-2; some will utilize some of the other conservative forechecks I will mention in a minute. And nearly all teams are ready to use some variation of a trap when they're looking to close a game out late, due to its conservative style. The reason the 1-2-2 is an attractive fit for trapping is that it only has one forechecker pressuring a puck-handler and puts four bodies in the neutral zone. But most teams, again, just play a standard version that hinders the opponent a bit but doesn't go all out to stop it. Here's an example of a standard 1-2-2 in action, with a good explainer from a coach(y) perspective (beginning of the clip through 0:56):

F1 is pretty far up and decently aggressive, cutting off the puck-handler's lateral passing option, forcing a pass up, where the wingers are positioned, the line is held by the defensemen, and it forces a dump in.

And then here's an example of a very trappy 1-2-2 in action (0:29-0:37 of this clip):

You notice that F1 for Columbus barely applies any pressure on the puckhandler Edler (VAN23), not doing much of anything to take away Edler's passing options (unlike the way F1 behaved in the previous clip). Meanwhile, F2 and F3 are so far back that you have four players right along the blue line:

Compare that to the preceding clip, where F2/F3 were tighter up in the neutral zone next to the opposition forwards. The difference is that while the previous clip forced a dump in, here Columbus is ceding a lazy entry but is going to make sure absolutely nothing comes of it and indeed, nothing does. The conclusion of the clip shows it working perfectly, as Pettersson (VAN40) drives right into the middle all alone and fires a shot that's blocked by the horde of bodies guarding the high-danger areas. They weren't as interested in forcing a turnover, but instead were willing to just wall off any dangerous looks, and mission accomplished.

1-3-1 Tampa

This is referred to as the "Tampa" alignment because it rose to prominence during the Lightning's 2011 run to the Eastern Conference Finals. Not nearly as common as the 1-2-2, the 1-3-1 is different because it is almost always a trap. It's not used much in the NHL these days, as it seems to have been replaced by the 1-1-3, which I will explain next, but this is a very rigid alignment that as I mentioned, is almost always a trap. The advantage of this alignment is that it completely takes away the middle of the ice, which is the area where where the high danger chances most often come from. The play is pushed to the outside and long passes through it are extremely difficult, and rush opportunities are pretty much eliminated. As a result, dump-ins from the opponent are even more common and therefore, this kind of system is most often employed by teams with a good puck-handling goalie, as well as those trying to close out a game, or those facing an opponent with a potent offense. Here's a clip of it in action (3:03-3:24 of this clip):

Pretty simple, the Lightning slink back into the 1-3-1, the Caps have little chance of making any quality passes or entry through it, so the puck is just dumped in. At this point, the Lightning then can go retrieve it and begin their zone exit sequence like we talked about last time. That's a NZ forecheck working to perfection.

1-1-3 NZ Forecheck

This has become all the rage in recent years, another rather conservative but also versatile system that the aforementioned Trotz uses as his style of trap, first riding it to glory with the 2018 Washington Capitals in the Stanley Cup Playoffs and since infusing it with the Islanders. Like the 1-2-2, this can be used to both trap and be more aggressive depending on how it is meant to be used. The 2020 Stanley Cup Final was the epitome of this, with both teams using the 1-1-3 but differently: Dallas used it passively to trap and slow down the potent Lightning, while the Lightning used it to be aggressive and force turnovers, creating chances the other way.

It's a lot like each of the previous two alignments I've mentioned, except it offers more flexibility and aggressiveness than the 1-3-1 and a unique defensive advantage compared to the 1-2-2. The aggressive advantage it has on the 1-3-1 is that it puts two forwards up the ice who can make plays, hunt the puck, and pressure, as opposed to just one like the 1-3-1. As for the defensive advantage it has on the 1-2-2, it defends the defensive zone blue line better than the 1-2-2, putting three players back there instead of just two, making it even more effective at denying controlled entries and shutting down the rush offense (the Jets employed this to counter McDavid and the Oilers' rush offense this season). In that way it's sort of the love child between the 1-2-2 and the 1-3-1, a nice stylistic blend that allows you to both pressure and defend competently. No wonder it's become so popular recently. Here's an example of the 1-1-3 in action, clogging the neutral zone and forcing turnovers:

Again you can see how F1 and F2 are allowed to pressure a little bit through the middle, while still having the crushing back line ready to hold the defensive zone and deny any dangerous entries, a hybrid of conservative and aggressive styles.

2-1-2 Pressure

This is the most aggressive forecheck we'll discuss here. As you may expect, this is often employed by teams who are trailing, as you have two forecheckers deep, pressuring both the puck carrier AND the most likely passing outlet. In that way, it functions almost like a man-on-man scheme, where every one of the opposition players are accounted for, and thus a small mistake can result in a turnover. It's a lot like a full-court press in basketball in the way it attempts to turn the puck over, but also like a full-court press, when it breaks down, it can result in easy rush chances for the opposition, which makes it a risky gamble. Whereas the 1-2-2 and 1-1-3 try and clog the neutral zone to stop the rush, the 2-1-2 is susceptible to it.

I like the following video because it explains in better terms how the scheme functions like man-on-man coverage, and how each component of the ice (puck handler, middle, both walls, D-to-D pass) are taken away aggressively, as opposed to swarming the puck carrier, which is how the 2-1-2 behaves in the OZ:

Again, it's a risky system because if any one of those players blows their assignment, you can get a rush against you, without a last line of defense that exists in the 1-1-3, and without the mass of bodies like the 1-2-2. But, the same can be true the other way, one small mistake by the opposition and you get a turnover and a rush chance. Scared money don't make money.

So, which strategy is best?

I don't think it's really possible to say that there's a "better" strategy. Like all games, hockey evolves over time as new strategies and ideas enter the mainstream, but I think it's not that things become outdated the way they do in football. In football, the game evolves and leaves the old concepts in the dust. It's hard to picture the predominant, no-passing type offenses of the 1960s and 70s ever re-populating the NFL or the NCAA again on a grand scale. But in hockey, many of these things are cyclical. Jack Han has written about the manner in which strategies that modern NHL teams employ in both forechecking as well as special teams are not radically different than those employed by teams 30 or even 40 years ago. So when the neutral zone trap rose to prominence in the 90s, a lot of teams latched onto it, but I don't think that's because it was necessarily a "better" way to play hockey. And the trap it should be noted, had its roots in the 1970s Montreal Canadiens and was not really a new concept (Jacques Lemaire said he learned the trap from Bowman, who had been his coach on the 70s Habs), it's just the manner in which it was being deployed was new.

In reality, the system you employ as a team should be stylized to fit your team's personnel. Teams with lots of good skaters and talent should employ something like an aggressive 1-1-3 or a 2-1-2 in my mind, to utilize the advantages of your roster, while teams with less talent are probably better off with a passive 1-1-3 or a 1-2-2 trap. A team with a mixed amount of talent may be best off with a vanilla 1-2-2 alignment. And every team should be prepared to change looks depending on the game situation, and how much pressure they need to apply on the opponent, in the same way a defense in football is ready to dial up a blitz in a certain situation, even if they're not a blitz-heavy team in their base defense.

There is definitely a defensive bias in hockey. Teams that score a lot but struggle defensively are castigated about "not playing defense", while teams that trap and can barely score and lose 2-1 games are rarely roasted with the same fervor about "not playing offense". Fans love to talk about when a high-scoring star player struggles defensively (Connor McDavid, for many years) but rarely talk negatively about all the defensive forwards who can't generate a scoring chance to save their life. It's that culture that has helped let these defensive styles flourish, but we also just watched the most dominant team in the NHL roll to a second straight Stanley Cup last week without employing a passive trap as their base system.

Ultimately it's up to the coach to make the call. The 1-1-3 is en vogue right now, but maybe in 20 years the 2-1-2 will be the base system, or maybe something totally new and wacky like a 3-1-1 will be the new strategy on the block. It's hard to see where things will go, but choosing a system to run, and then getting the players to learn it and fit within it, is the most important task a coach has at both the NCAA and NHL level.

That's all for today. If you have any questions, feel free to comment, and I'll do my best to answer them! We'll be back next time with a deep dive on special teams, looking at power play and penalty kill strategies.

Can you explain what it means to "pinch?"

It's when a defenseman in the offensive zone moves forward from his spot protecting the blue line to either put pressure on an offensive player who is in the process of getting a loose puck to create a turnover or to win a a loose puck so as to keep possession in the offensive zone.

Ed: It's also what many youth hockey parents scream at the defensemen on their team to do, most of the time when it's totally the wrong decision.

Agreed. The best football analogy I can think of is that it's kind of like a corner blitz. A normally defensive/backing up player moves forward aggressively. And hopefully a forward/safety rotates over to cover.

It doesn't happen all the time, and it's something somewhat aggressive.

Having grown up in Canada and played competitively for 20 years, I don't think I've ever heard neutral zone defensive play referred to as forechecking before...

Me neither. I've always thought of forechecking taking place in the offensive (forward) zone.

Yeah I don't think anyone says that the act of playing in the neutral zone is "forechecking" necessarily, but the actually scheme itself from the coaching side is referred to as a "neutral zone forecheck"

Good solid write up Alex. Playing to your personnel and having lots of changeups is key to team success. A team may run multiple looks depending on game situation, score, and even which line is on the ice.

So what does Michigan tend to use? Is it dependent on their personnel or does Coach Pearson have a preference for any of those styles?

Keep your eye out for an article on that in the near future ;)

I look forward to it, this has been a great series.

Excellent writeup. I am going to bookmark this for my friends and family members who think I'm full of shit when I talk about hockey 'plays' and 'alignments' in a similar manner as football.

Also similar to football, the type of neutral zone trap or forechecking a team employs can often depend on which personnel is on the ice.

Are you doing different breakout styles that the opposing teams use to try to break the specific forechecks they employ? I think that would be an excellent cover.

I should recommend these writeups to the new hockey mom who refused to believe that the space between the goaltender's legs is called the five-hole. She insisted that it is called the pie-hole because, as she demonstrated with her hands, that is how it is shaped. Would have been funny had she not spoken to me as though I was obviously stupid.

no NZ trap?

Bit antiquated these days, but I thought some teams (ND?) might stoll play it on occasion and I'd be curious why it was so effective back in the 90s and why it went away after 2010 or so.

Yeah as I mentioned in the piece, the NZ trap is definitely still around and a number of teams ran it as their base this season in the NHL (Red Wings, Stars, Columbus, Islanders) but there isn't really one play that is "the neutral zone trap". It's generally a stylistic thing that can be expressed through a 1-2-2, a 1-3-1, or a 1-1-3. And yeah tons of teams do it in college hockey... most of the ECAC teams, as well as Notre Dame, and others. Michigan definitely trapped a bit a few years ago when we had a lot less talent (when Luke Morgan was on our second line lol).

There's no one real answer as to why the trap rose to prominence in the 90s, but my understanding is that Lemaire instituted it in NJ because it fit well with the personnel, given that he had really good defensemen (Niedermayer, Stevens, Daneyko), a great puck-handling goalie (Brodeur), and physical, forechecking forwards (the Crash Line (Holik, Peluso, McKay), Claude Lemieux, etc). The Devils rode it to the '95 title, steamrolling everybody that playoffs including the loaded Wings. The next year, a few teams tried to do it and as I've understood it, it was the '96 Panthers who really sealed the revolution, because that team had almost no talent, and certainly didn't have the defensive names of New Jersey, yet they managed to shut down the most dominant offensive team in the league that year, the Penguins (with Mario and Jagr). That kinda showed people that you didn't actually have to have top tier defensemen and goalies to trap successfully, pretty much anyone could do it if they were coached well enough. And in an era of pre-cap low parity, when many franchises were constantly on the verge of financial insolvency, it made a lot of sense to just get some physical depth forwards to fill out your roster and try and trap your way to glory because you weren't gonna afford the athletes to win a footrace with Detroit or Colorado' talent.

Building off of that, the trap really worked in the 90s NHL in particular because of the quirks of the rule book. In the era of the two-line offside (one of the dumbest rules in sports history), it was a lot harder to use vertical stretch passes to try and pass through it, forcing teams to have to try and skate through the mass of bodies, which was damn near impossible. Additionally, in the era before the trapezoid, goalies could come way out to field any dump-ins and act like a third defenseman, pushing the play up the ice quickly, which Brodeur and Turco in particular used terrifically. The NHL changed both of those rules after the '05 lockout as a way to neutralize the trap and boost scoring.

That didn't eliminate the trap, nor did scoring perk up immediately, although it has started to in the last 5 years. I'm not sure why exactly other than perhaps the amount of talent in the league has gotten so good that teams just don't feel like doing it as much.

Life long hockey enthusiast but just TV / beer league / pond hockey and I learned a lot! Thank you

Comments