Neck Sharpies: Making Space for Speed

So you know Josh Gattis has a philosophy. Michigan's new offensive coordinator, a former safety with a short trip in the NFL, spent the bulk of his coaching career as part of the brain trust propping up James Franklin. Two of those seasons came under Joe Moorhead, now head coach of Mississippi State, and one of the premier offensive minds in the game.

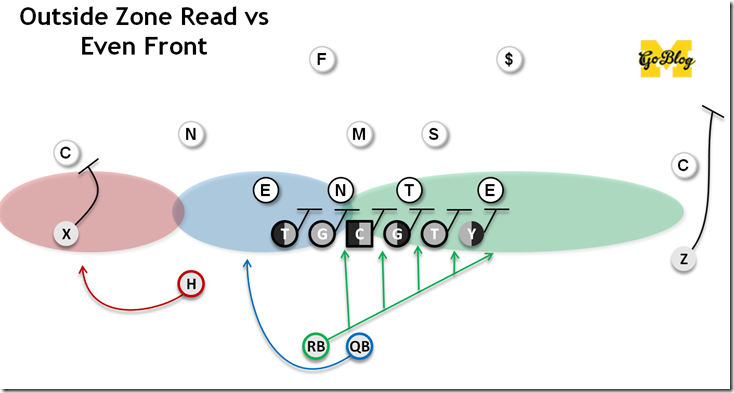

Now, the concept of speed in space is just barely more modern than toughness. What we're really talking about when we say "philosophy" is a slider: how much do your play designs emphasize that one aspect, and how. In historical Franklin spreads—and Rich Rodriguez offenses I should add—the stress put on the defense is extremely horizontal.

Verticality was an important changeup of course but note that resources in his base play are all about generating horizontal spacing: the defensive front has to control outside gaps that are widening every second, with the QB run and a pre-snap bubble read to force defenses to keep their material to the backside.

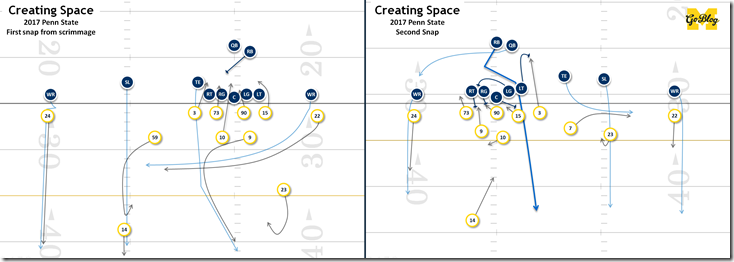

Moorhead's philosophy, however, is extremely vertical. Take the first two plays he ran against us in 2017:

These plays also threaten horizontally—that second play is an Inverted Veer, the modern cousin of the standard "get to the edge or cut behind overpursuit" play of the 20th century. He's flipped the QB and RB for some extra flavor but the base concept is to drag three defenders far away from the play on the wide side and threaten to run outside the other way, pulling a backside guard and optioning the last guy on the line of scrimmage to get numbers over there.

But note how he uses the receivers here. In both instances Moorhead is using three of his eligible receivers to go long, and running a fourth underneath. It's a big material commitment, but a hallmark of his offenses. And they're not just for show; Moorhead's offenses almost always feature one or two receivers with double-digit TDs and 17 yards per catch on 55% catch rates to back up his Dr. Strangelove reputation.

Other hallmarks of Moorhead designs are he likes to get underneath defensive players moving laterally before and after the snap, and he likes to use creative options and things that look like options to freeze edge defenders. Coach Matt Wyatt of RenasantNation.com had a great video last year on Moorhead's offense and the creative ways they got the ball to Saquon Barkley, but see if you can see these concepts at play:

Warning: Our 2017 Penn State game features after some OSU & MSU

Given Josh Gattis really comes from the Franklin tree, I was very interested in the Spring Game to see how much of Moorhead he'd adopted. The answer: I think most of it.

[After THE JUMP: Al Borges?!?]

--------------------------------------------

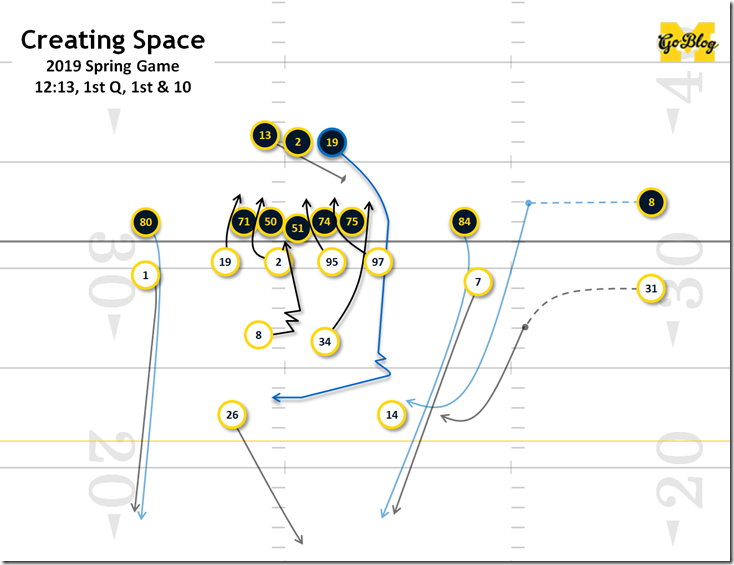

So here's an early play that most Michigan fans will remember as "hello, Mike Sainristil":

now with sound!

It's a crossing route from the slot receiver, who's lined up as a second running back. It also was a Rock, Paper, Scissors win, since it beat a six-man pressure. The absence of any linebackers dropping is what turned a seven-yard completion into a touchdown run, but see if you can spot all the Moorheadian elements in its design:

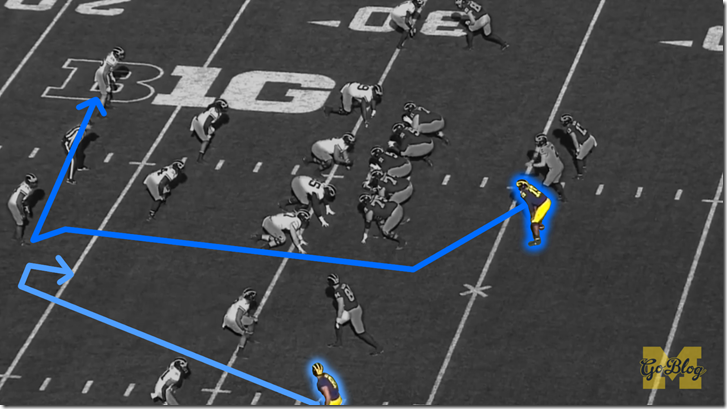

Right off the bat you've got a minimum of two guys attacking vertically. They're running directly at the safeties to start—keep those guys back and out of the way of the play—but those routes then turn into a sideline and middle of the field attack:

This has a good chance of opening up a 1-on-1 matchup between two good downfield threats. If the defense commits a third defender to those deep routes, well, more space underneath.

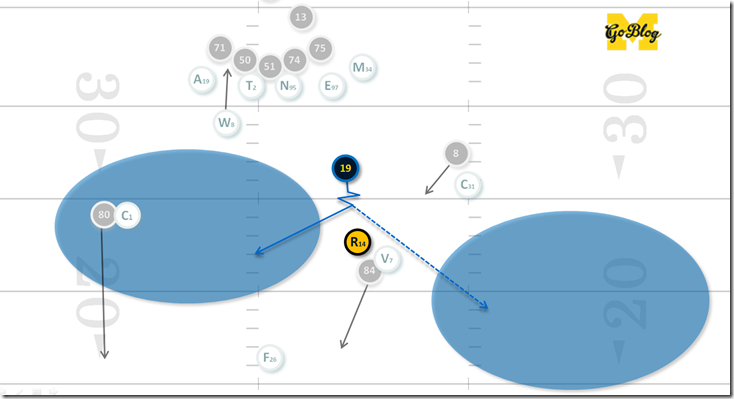

The underneath read is just a two-man stick concept that you'll find in any West Coast playbook: isolate a middle zone defender horizontally between two receivers and throw it to the one he's less likely to get to:

So far this is nothing you won't find in an Al Borges offense. I use Notorious Al not because hur durr Borges but because the motion and the initial attack are very much like the best part of the Borgesian passing philosophy:

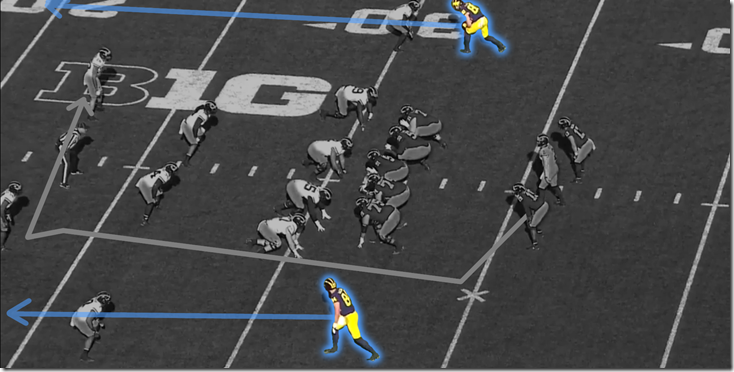

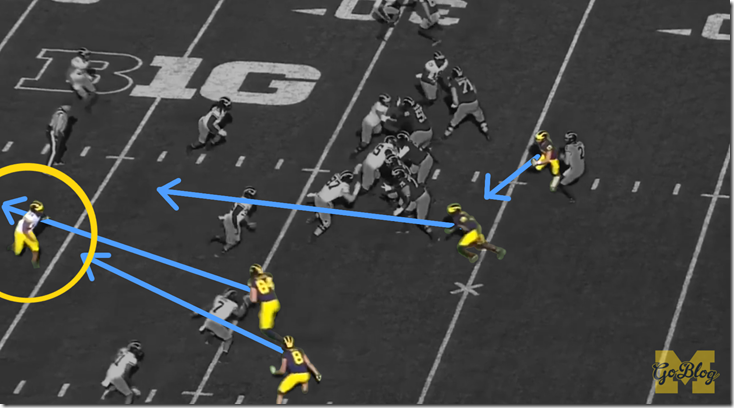

I took this snap because it's the last frame before spring game cameraman went back to nostril vision. Look at Josh Metellus (yellow circle) and how many dudes are running in his general direction. Put yourself in Josh's mind here. You've got a tight end running right at you, and you've got to make sure you're over him long enough for Khaleke to not get instaburned before the free safety—J'Marick Woods—can be of assistance. Behind McKeon there's that athletic freak Ronnie Bell coming on a slant or snag. Then there's the H, Mike Sainristil coming out of the backfield, and maybe Tru Wilson going out into the flat behind him. Yeah, Josh, you've got your job in this defense and your buddies' have theirs, but it's hard to stick to your programming when you're just some draftee and the entire invasion is pointing at you. This was Borges's favorite way to start a play too.

The difference, however, is in the details. Borges never seemed to care who was doing what (in fact his offenses were most successful when his players changed the call), and never seemed to think about what defenders thought about. Josh Gattis is a former NFL safety. He knows exactly what's going through Metellus's mind at the start of this play. And he also knows exactly what messes with it.

The broadcast didn't catch the opening play, but it was out of a similar set with similar motion, and ended with an end-around to Sainristil. So that's in your mind right there when both receivers to that side run right at you, and even though you're doing your job and picking up Sainristil out of the backfield, you're now faced with a new dilemma:

Metellus has Sainristil wherever he goes, and at the point of the shimmy there's a very credible threat of the slot bug going to the fade route. We've gone over this a thousand times with Michigan's Cover 1: unless you're possessed with NFL-caliber physical gifts, you have to keep outside leverage to prevent the fade because you can always break on an in route. Metellus has to stay over that dotted line route until Sainristil commits to an inside break.

Here's where the personnel comes in to play. What a little slot bug gives you right there is that elite acceleration off the in-break. Metellus has less time here than he would against, say, Tarik Black. Maybe even Donovan Peoples-Jones. That's your speed in space, and it's very Moorheadian. You can right away see the structural problems these attacks create for a defense like Michigan's—if you play a safety with outside leverage you need to keep a middle linebacker around to cover the inside.

But this also creates problems for the base zone defenses that Michigan will face. Two vertical receivers against Cover 3 will result in this same gap when you lose the other safety to getting over top of those routes. Against Cover 2 and Quarters the McKeon route should drag away the strong safety and put the slot receiver on a linebacker. And the more Michigan reps this stuff, they can start adding that fade route as an option route, and really unlock the potential of their slot receivers.

And it all comes back to the same principles:

- Put the fear of horizontality into the defense

- Create spacing and/or advantageous downfield matchups by running multiple vertical routes

- Dictate matchups between your best athletes and structural weaknesses in the opponent

There's another thing that I am almost certain was part of the design. It's this:

I saw this a few times from Penn State in 2017 and then I saw a receiver get yelled at for running a similar route too short of referee. Metellus is already too far behind for it to matter but putting the ball just past the official creates a pick not unlike that of the mesh play. You can't be too obvious about it, but few teams are beneath using the extra matter in the middle of the field to win those crucial inches. I'm sure as a safety this drove Gattis nuts. If so, his revenge tour is off to a promising start.

I'll get into a run that also used these concepts in the next one of these.

Franklin's a pretty extreme CEO coach. I was never very enthralled with him as an OC. He coached with a lot of guys I've had to scout so I watched a lot of pre-Vandy Franklin offenses. What he's the best at is selling himself. You point out that's recruiting, and you're right--if he can recruit great players and great coaches what does it matter if he's not as good at coaching itself. Sometimes all you need for a successful business is a great salesman.

Props to him for that, but in the context of trying to figure out what we have in Gattis, I did want to kind of knock Franklin as an OC because Gattis followed Franklin from Vandy to PSU, and if Gattis is another Ricky Rahne--a guy who understands the plays but not the philosophy behind them--that's a thing we should be on the lookout for. Moorhead's genius was subtle: he didn't just know the plays but when to put them out there to inflict maximum damage. He knew, for example, to go to a run with a cutback lane on Play 2 after a long bomb in a rocking night game environment, in case Gary's ears are pinned back and he wants a DEATH SACK. Franklin on the other hand is the guy who ran stretch zones just twice (both worked) in 2015 after Indiana just eviscerated us with them and Ohio State was about to.

Comments