2019 spring game

THIS IS NOT A BASKETBALL COACH! I've had this written for days but feared coaching news will hit the moment I post it. So maybe this will jog the coaching news.

One of the great questions this spring is how Gattis plans to incorporate the stuff Michigan's been doing with his ideas. Draw up a play coach twitter already found this one and drew it up:

Boundary Pin & Pull RPO is already tough for the Defense to Diagnose!

— Coach Dan Casey (@CoachDanCasey) May 4, 2019

➕ Adding Swing from the Pistol RB really puts the Overhang Defender in a Bind

✌ Love seeing RPO out of Two Back!

Excited to see what @Coach_Gattis does in Ann Arbor! pic.twitter.com/JCDndCLRj3

…because it really takes you through how Gattis thinks. I also wanted to break this down because it shows how Gattis's changes to the offense are more of a renovation than a teardown.

THE STANDING STRUCTURE: PIN AND PULL

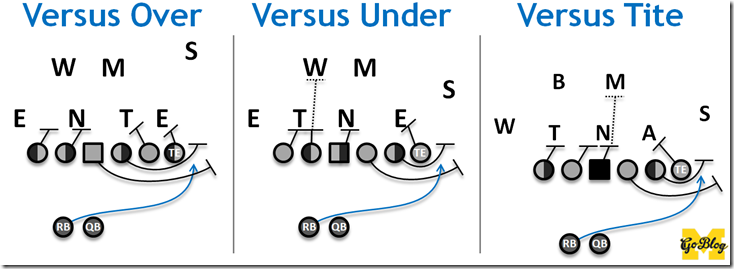

As Coach Casey said, the most basic part of this play is the "Pin & Pull" running concept. Michigan developed this over the course of 2018 against any kind of front willing to put its last DE inside the tight end (basically everyone but Northwestern and Michigan State). It's the mullet of running plays: zone on the backside, power on the front, with one of the pullers responsible for kicking an edge defender.

This won't be on the final exam. I just wanted to establish that this is something Michigan's offensive players have down so much that they were building traps and such into it. I also wanted you to get familiar with the ways that defenses can muck it up. The big one of course is those linebackers high-tailing it after the ball.

As Casey mentioned—and as I covered when we were first drawing it up last year—the nice thing about Pin & Pull plays is they're hard for the backside defenders to read. The linemen in front of them are blocking like inside zone, and you don't want to get caught over-pursuing against that. Then they find out they're supposed to be pursuing! Here they are running it against Indiana's Over front.

The guy who ultimately makes this tackle is #34, the linebacker set up in the middle of the field. The guy who's really the key to this play however is #43, the middle linebacker. If that dude shadows the running back and gets to the gap at the same time, it's no yards, or a blocker used up where he's in the path of where everyone needs to go. Let's watch him here:

#43, the linebacker who starts just under the hash mark

I mean it sucks to suck but he did everything he could up until physics and its good friend Michael Onwenu took over. If he's there, it means Onwenu isn't picking off somebody else. His arrival to this play is what made that signal in your fan brain go off that this play was probably going to end soon.

[After THE JUMP: What would Speed In Space Do?]

A few weeks ago I drew up a pass from early in the Michigan Spring Game to demonstrate how Josh Gattis has learned some Joe Moorhead tricks for using vertical space to open up room for his playmakers underneath. In the thread for that a user named UMmasotta asked an excellent question: What does Gattis do when field position takes away verticality?:

I'm curious what happens in red zone situations? I know Brian likes to say there's no such thing as red zone offense but if one of the core principals is to put vertical stress on the defense and said vertical stress is limited due to the proximity of the endzone, what does Gattis do? Obviously, every offense has to deal with shorter, goal-to-go situations. Just wondering if Gattis starts to look like everyone else in those situations or whether there is a "speed in space" concept that he can deploy there as well.

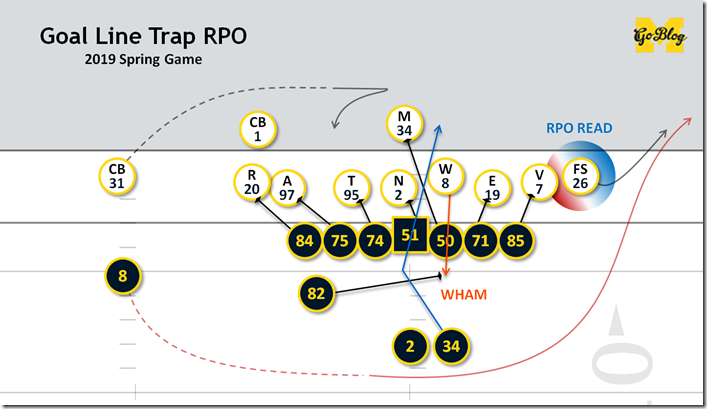

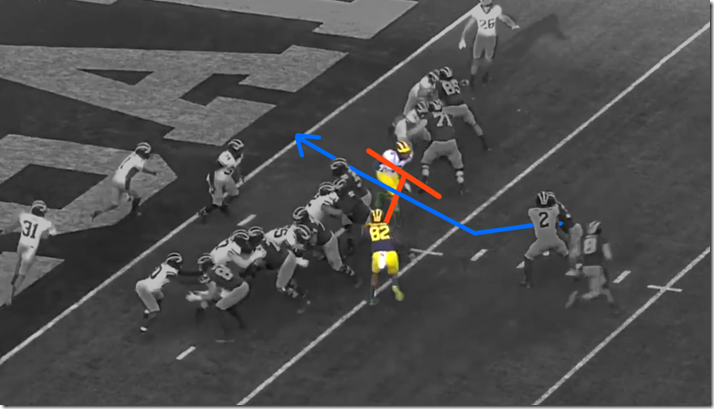

Gattis isn't going to put his best red zone plays on tape in a scrimmage, but we got to see at least one snap from close range that demonstrates how Gattis is still applying this same concept of isolating speedster in space. It's this run from the three-yard line that got halfway there, and almost certainly would have scored but for a little walk-on running back who momentarily thought he was Ben Mason.

Gap's that way—>, kid.

There's a lot to unpack here so bear with me. As Jim Brandstatter notes, they're in a "Harbaugh" look, i.e. three tight ends or "31" personnel. Unlike Harbaugh looks from Stanford or Michigan 2015-'17, the quarterback's in the gun, and unlike in 2018, the running back is in a standard gun spot as opposed to the pistol (behind the QB) setup they favored last year.

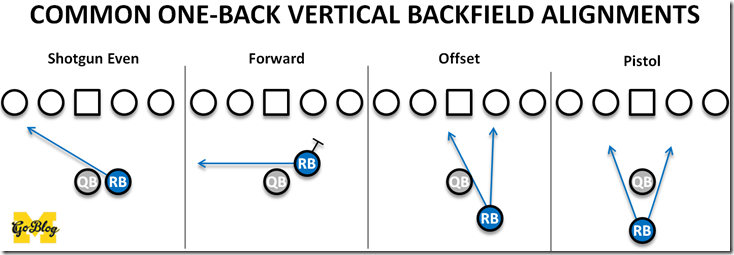

Running back placement is often a sign of offensive intent. A back beside the quarterback will be coming into the handoff/mesh point diagonally, i.e. an angle for running off-tackle. Move the running back behind the QB and you make that angle more downhill, threatening interior gaps. The pistol formation puts that RB in an "I" stance, threatening both sides of the formation equally. Some coaches (e.g. James Franklin) even have the back a little bit in front of the quarterback, creating a completely horizontal cross that's helpful for running out sideways.

You are, of course, by no means limited to running on these angles; it just means your back is going to have to redirect his momentum to go somewhere else. In our goal line play Gattis has aligned his RB even with Patterson to show the defense a likely attack off the side with two tight ends. Last week we went over a pin & pull play that attacks from a similar alignment.

Gattis is going to attack the backside "A" gap here, but he wants that edge run to the frontside in the defense's minds:

Offense is on the bottom now because I want that one coach to stop DM'ing me about it.

The plan for getting into that A gap is to "Trap" or "Wham" (the word doesn't matter*) block with Nick Eubanks. This is some 2015 Harbaugh stuff that we haven't seen much of the last few years. It's similar to the split zone play they ran a lot last year as a primary counter, where the tight end comes across the formation and thwacks a defender who thinks he's getting optioned, whereupon the ballcarrier slips behind the block. This time they're letting the backside linebacker, Devin Gil, blitz right up that gap. He'll meet Nick Eubanks slipping across the formation, get sealed on the hash, and leave plenty of room behind Ruiz/Onwenu to set a path to the endzone.

So far this is pretty standard stuff—barely any Gattising at all. But that's not all that's happening here. Shea's looking at something. And there's someone else in the backfield. Someone pretty fast. And there's a sunlit region to explore.

[After THE JUMP: Enough with the thwack blocks; show me the #SpeedInSpace part!]

-------------------------------------

* [Some coaches say a "Trap" block is when a TE or FB hits his target horizontally while a "Wham" block is when he makes vertical contact. Others say the difference is a trap happens outside the tackles and a wham is inside. Surely this will elicit a response from Space Coyote et al. in the comments; personally I like "Wham" because of the line in Suffragette City.]

-------------------------------------

"Never mind the maneuvers, just go straight at them." –Admiral Horatio Nelson

"Never do this." –Dude who fought at the Somme

[GAME OF THRONES SPOILER ALERT]

So yesterday military and football strategists were dunking on the Night King's gameplan for taking Winterfell. Leaving aside the unique military advantage of being able to convert your enemy's defeated soldier's into fresh troops, iceman here had a thousand lifespans to plan his attack on humanity, and somehow the best he could come up with was to walk straight into the Godswood.

[END SPOILER]

A direct frontal assault could be your best chance in some cases, but if we learned anything from 20th century warfare, it's that that you should probably avoid it when you can. That's not just my thought. In 1954 the British military historian B.H. Liddell Hart published Strategy: The Indirect Approach, a seminal work on military history largely informed by the lessons of two World Wars he participated in. The book, which is in the public domain, discusses the strategies of great generals and their counterparts in various time periods and theaters, and is well worth the (short) read that most people who reference him never undertake (especially his take on Ludendorff). Hart favors tactics that get the enemy moving one way then hitting them where they ain't:

To move along the line of natural expectation consolidates the opponent's equilibrium, and, by stiffening it, augments his resisting power…An examination of military history—not of one period but of its whole course—brings out the point that in almost all the decisive campaigns the dislocation of the enemy's psychological and physical balance has been the vital prelude to a successful attempt at his overthrow.

Admittedly, Hart's conclusions are colored by his biases, and he is so often misquoted by wannabe business Napoleons that most people who've heard of Hart now roll their eyes at his mention. But the guy had a point, and I think if he was alive this spring, Hart probably would have really enjoyed some of the things he saw in Michigan's running game under new offensive coordinator Josh Gattis.

Others did as well:

Q pin/pull concept paired a flare RPO. @UMichFootball ran this a ton out of 22 personnel. Good stuff @Coach_Gattis! pic.twitter.com/FHsaG96S95

— All-22 Film Breakdown (@All22_Breakdown) April 19, 2019

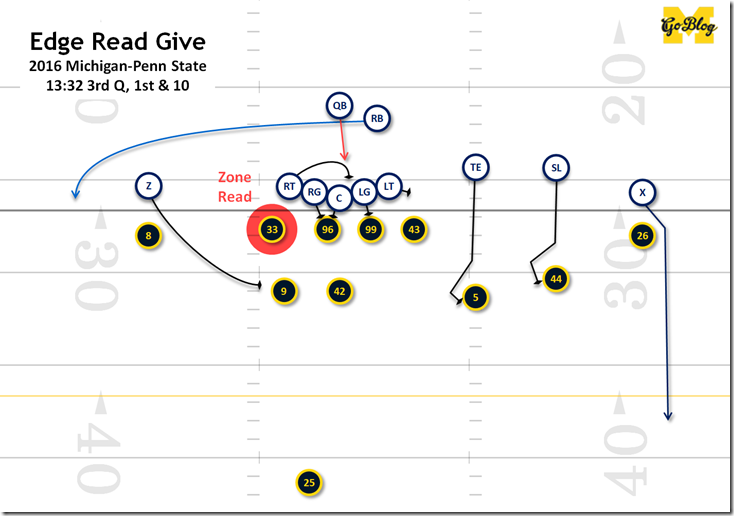

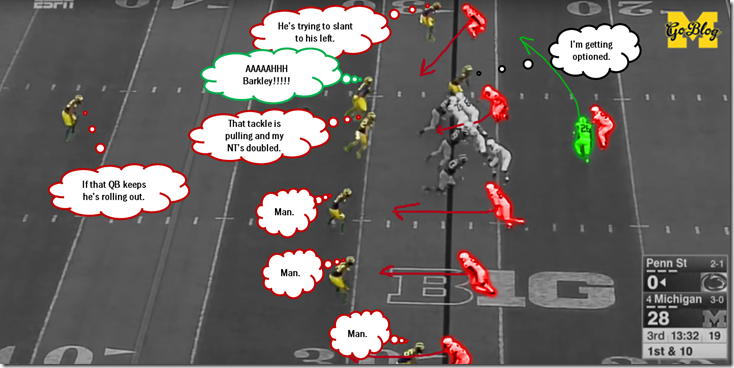

Brian commented that these plays reminded him of the way Scott Frost attacked us in 2016. Here's an example of one of those things except run two weeks later by the offensive staff Gattis was a part of at the time:

A lot of plays could lay claim to represent the Indirect Approach school of rushing offense—simple outside zone is a good candidate—but here you really see the Hart philosophy at play. You've got three frontside receivers and a backside tackle pull directing defensive material away from the point of attack. Look at all the guys whose reads are telling them to move/stay to the (offense's) left:

That's a lot of red.

A zone read of the unblocked defensive end is there as a contingency; worst-case scenario the optioned DE (Taco) decides to fling himself upfield into Barkley's path, and quarterback can dive forward behind a puller and a double-team, still a numeric advantage.

The way to defend this from Michigan's base cover 1 would be for the weakside linebacker (McCray, with the green edged thought bubble above) to beat the crack block from the top receiver, and for the cornerback on that side (Stribling) to see the crack and "replace," i.e. take over McCray's edge duties and force Barkley back inside. They both misplayed it and Barkley picked up 30 yards en route to…

/checks drive chart

/looks at scoreboard

/re-checks drive chart

So that's what we mean about getting the defense moving one way to attack elsewhere. This play is a stark (not sorry) example of this running philosophy. Now let's see how 2019 Michigan's using it.

[After the JUMP: Gattis hasn't given up]

the kind of accounts that point out cool new football stuff are embedding Michigan plays again

Let's use our collective bad memories to grow more confident in our offense

I've watched Don Brown defenses, and there's supposed to be a safety.

On the benefits of facing the new-look offense and young players standing out so far

This offense brought to you by the word 'energy'

It felt awful. It felt stupid. It felt ancient. It felt self-inflicted.

except last year when there was no game and I just deleted it

17