Offensive Balance

Inspired by a tweet from Chris Brown a.k.a smartfootball on this interesting but largely meaningless article from Rivals I decided to put together a post on offensive balance. This is going in place of my normal Monday post and I should be back in a week or so with Brian’s requested special teams primer.

Game Theory and Play Calling

Game theory suggests that teams will adjust their choices so that the average value of each choice (run or pass) will be equal. We also know that not all coaches are rational decision makers and there are likely very few who understand what game theory is. That is where nerds like myself come it to explain on blogs and help them understand.

The thinking goes like this: a team is really good at running the ball and really bad at passing the ball, but they are perfectly “balanced,” half their plays are rushes and half are passes. Since there is more value on a running play than a passing play, it doesn’t make sense to be calling so many pass plays, so the first adjustment happens and this team starts calling more rushes to take advantage of their more efficient running game. At some point, the defense responds to the new strategy and begins to stack against the run which of course makes success in the passing game easier. If the offense is playing optimal strategy, their final mix will be one that garners the same value for each play, regardless of whether it is a run or a pass, even if the distribution of plays is not 50/50.

Charts? Charts!

This is how every team in the country fared on a per down basis in both rush and pass. The diagonal line represents balanced results on a per play basis. Teams on the top right are balanced and successful, teams on the bottom left are balanced and unsuccessful. Teams to the left of the line (Northwestern, Iowa, Michigan St, Notre Dame, Penn St, Wisconsin, Indiana and Minnesota) should pass the ball more to become more optimal where teams below the line (Michigan, Ohio St and Illinois) have the opportunity to run the ball more to become more optimal. Purdue sits right at the intersection of all lines, balanced and mediocre. Most of the teams in the Big 10 where within reach of balance with the notable exceptions of Michigan St and Notre Dame, two teams that couldn’t get their rushing outputs to match their passing success. Time for another chart.

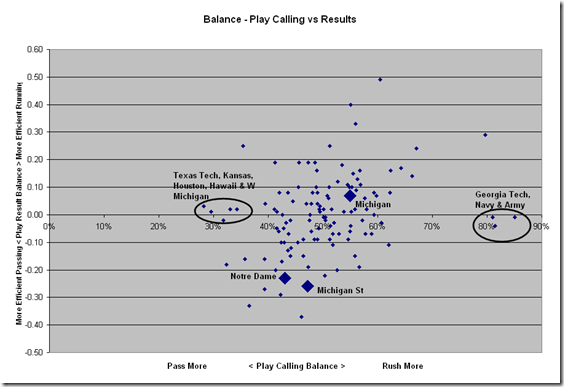

In this chart you can see how balance in calls does not necessarily equal balance in output. In fact, some of the least balanced play callers, on both ends of the spectrum no less, produced the most balanced results in output. Teams who rushed over 80% of the time like Georgia Tech, Navy and Army got almost the same value from passes as they did form rushes. On the other end, pass happy squads like Texas Tech, Kansas and Houston saw similar production on a per play basis from their running games as they did from their passing games. These teams are still running or passing teams, but their play calling balance has found an equilibrium where they are maximizing their total points by finding balance, even if they are calling a lot more of one type of play than another.

You can see that Michigan St and Notre Dame are both outliers in their respective deviations in success between run and pass, despite being towards the middle (especially MSU) when it comes to run pass selection.

Other Notes

This data does not include games for any team versus non D1 opponents (Baby Seal U). Only plays when the lead is 2 TDs or less or if the game is still in the first half are counted. Points per play uses my expected points model and is adjusted based on opponents played. Interceptions are included in this analysis but fumbles, fumble returns and interception returns are not. Including fumbles pushes the balance to passing as fumbles are more likely to occur on running plays than pass plays. Most of that difference is negated if you include returns as interceptions are much more likely to be returned than fumbles and the total value of interception returns is nearly equal to the difference between fumbles on running plays versus passing plays. The net of it all is that excluding fumbles and returns does not materially affect any of the data above.

I expect for us to be mostly run but not nearly as much as West Virginia. So I expect us to be somewhat balanced.

Doesn't football strategy favor running the ball a little more even if the yardage output is the same? I have seen studies that suggest that "all yards are not created equal" and that fumbles have little effect upon a game while interceptions have a huge effect. I suspect that the favoritism towards running is the result of down and distance/posession strategy in football and the way that it favors the low variance of running as opposed to the high variance of passing.

April 30th, 2010 at 11:25 AM ^

You are right that based on the tradition comparison, yards per play, there is an unstated advantage to running because of the interception risk in passing. With this analysis, however, it is not based strictly on yards per play and interceptions are included, so the bias is removed. This is the best attempt I can do to take out all of the extraneous factors and get a true apples to apples comparison.

The counter to that line of thinking is in the evolution of the NFL over the last 10 years. Pass first teams make up the bulk of Superbowl champs, most notably the Pats, the Colts and the Saints.

April 30th, 2010 at 11:34 AM ^

Thank you Mathlete for merging my nerdy love of statistics and my inexplicable obsession with Michigan football on a regular basis. Your work is always appreciated.

April 30th, 2010 at 10:58 PM ^

as an example, if Team A averaged 1 point per run and 1 point per pass, while Team B averaged 5 points per run and 5 points per pass, wouldn't they both be at 0.00 on the horizontal access?

i.e. I can't tell if Georgia Tech sucked equally at run and pass, or excelled equally at run and pass, but they sure call a lot of run plays.

and I suppose I should look it up, but are you the one who did the analysis on play calling, where the definition of a successful play varied in yardage depending on which down it was?

I guess what I'm looking for is a way to find the coaches who both understood/planned their teams strength (run or pass) and understood when to call to the strength and when to call the "changeup" so to speak.

At least that's what I connected to the most in your setup, that you can't just call to your strength because predictability is a worse enemy than a weak O-line, or a fumble prone running back.

Anyway those were my thoughts on "cool charts, now what do i do with them"

and don't take that as sarcasm at all, I know enough about statistics to be amazed at your effort on this, just not enough to immediately say, "oh yes this proves it without a doubt"

You are right in that the second graph tells nothing as to whether a team was succesful on offense or not, just whether their playcalling was producing a balanced output. The primary objective I had with the second chart was to show that even teams that are the worst at traditional metrics of playcalling balance, have actually crafted very balanced outcomes because all plays yield roughly the same result, even if they are calling a lot more of one than the other.

You are correct in that all the data is based on down and distance. I think what you are looking for is all in the first chart. Teams in the top right box are teams that are effective at both the run and the pass. The teams that are in the right box and close to the diagonal line are the teams that are good at both and have optimized their playcalling selection (when accounting for down and distance). Hope this answered your questions.

I do like the way this line of thinking re-defines the notion of ballance from 50%run/50%pass to whatever mix of pass and run plays that allows you to move the ball and score consistently. In some ways it gets away from the idea that an offence must do all things well in order to be successful. You can be a pass happy Airaid team like TT and still find "ballance." You can have an identity as an offence, focus on doing something well, whether pass or run, and then do the other just well enough to keep the opposing defenses honest. In fact, it may be that by doing one thing well, you make it easier to succeed at the other when the other team begins to cheat in order to take your strength away.

Comments