defensive schemes

This series is a work-in-progress glossary of football concepts we tend to talk about in these pages. Previously:

Offensive concepts: RPOs, high-low, snag, mesh, covered/ineligible receivers, Duo, zone vs gap blocking, zone stretch, split zone, pin and pull, counter trey, inverted veer, reach block, kickout block, wham block, Y banana play, TRAIN, the run & shoot

Defensive concepts: The 3-3-5, Contain & lane integrity, force player, hybrid space player, no YOU’RE a 3-4!, scrape exchange, Tampa 2, Saban-style pattern-matching, match quarters, Dantonio’s quarters, Don Brown’s 4-DL packages and 3-DL packages, Bear

Special Teams: Spread punt vs NFL-style

We've been throwing around a term for how Michigan is playing defense this year a lot lately and haven't stopped to explain what it means: Playing to Spill.

Definition

Playing to spill is a defensive technique where the force player (edge defender) dives inside of a kickout block while another defender pops outside. This is done on the fly, usually against power runs, as a way to screw up blocking assignments and force the ballcarrier into this now-unblocked outside defender.

A play

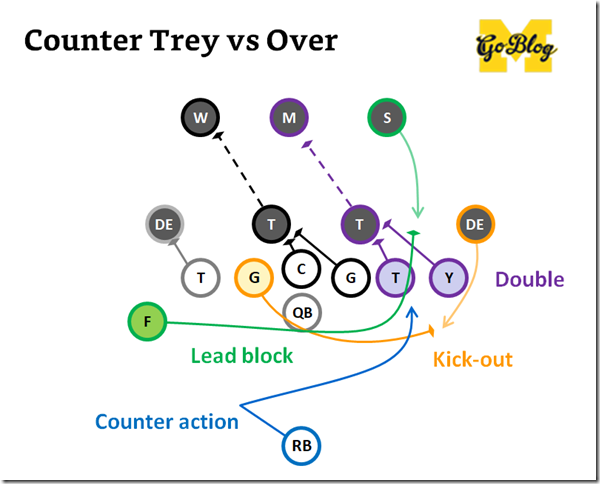

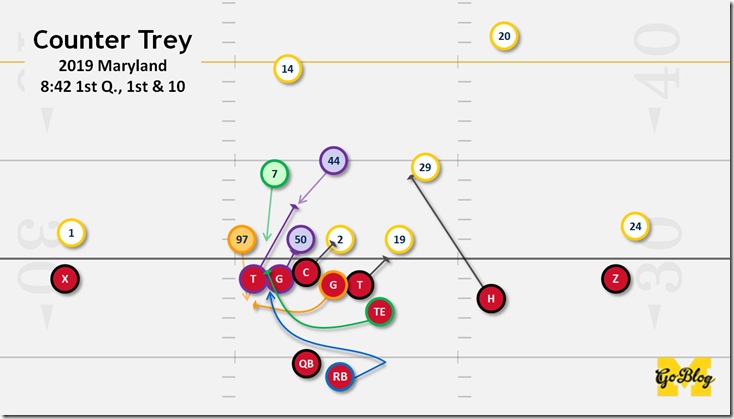

So Maryland—not for the reason you might think—runs an offense extremely similar to Michigan's. Particularly this week they were heavy into arc zone read and its counter, split zone, plus pin and pull and its flipside, Counter Trey. We've discussed Counter Trey on here a bunch. It's Pin & Pull the opposite direction with some counter action in the backfield to get the defense stepping to the frontside before you swing the ballcarrier and a few escorts to the backside.

Locksley's Terps will kindly demonstrate this for us:

This is vintage Locksley: trying to get you thinking about a run one way so you're not paying attention when it goes the other way, then he thunks your edge guy outside, pins you inside, and rips somebody's heart out. On this play you see the tight end come across the formation and the running back step that way like it's going to be that edge pitch Penn State liked to run, and it's a surprise when the ball goes the other direction. Michigan's defense wasn't fooled however.

Remember, the pulling guard coming across the formation is trying to kick out Aiden Hutchinson, DE #97 on the top of the line. I want you to pay close attention to Aiden's response to the kickout. The pulling guard wants Aiden standing outside all passively. Aiden has other plans; he sees the guard coming…

…and leaps inside of him:

Aiden has now placed himself in the intended running lane. But this is Maryland's most base play, and the guard doing the kicking knows how to respond to this: turn the end inside. If you recall Michigan was doing the same thing on their pin & pulls versus Illinois.

The difference is here Michigan's defense has an edge.

[After THE JUMP: a scrape exchange for power]

[This series is a work-in-progress glossary of football concepts we tend to talk about in Upon Further Review and Neck Sharpies, etc. Previously:

Offensive concepts: Run-pass options (RPOs), High-Low passing routes, Covered (ineligible) receivers/tight ends, Blocking: Reach Blocks, Kickout Blocks, Wham Blocks

Defensive concepts: Keeping Contain/Lane Integrity, Force Player, Hybrid Space Player, One-Gap Fronts, Coverages: Tampa 2, Pattern-Matching, Quarters and how MSU runs it

Special Teams: Spread punt vs NFL-style]

------------------------------------------

In the Iowa UFR Brian talked about how opponents had solved Michigan’s Peppers-as-Option-QB (we were calling it the “Pepcat”) package with an old fashioned zone read beater: the scrape exchange. Brian on the above:

Peppers is reading the DE and pulls; Iowa inserts a linebacker directly into his path since that DE is covering up the inside gaps the LB would usually be tasked with.

Since I watched the Rodriguez era at Michigan this is familiar to me. Also familiar to me: the various counter-punches Michigan threw at this. Remember that brief era when Carlos Brown and Brandon Minor were running directly off tackle for big chunks on the regular? That was due to Michigan's response to this kind of approach: blast that guy slanting even further inside, kick the linebacker out, and thunder directly to the secondary.

Since that was buried in a UFR I figured we might discuss scrape exchanges in some more detail here.

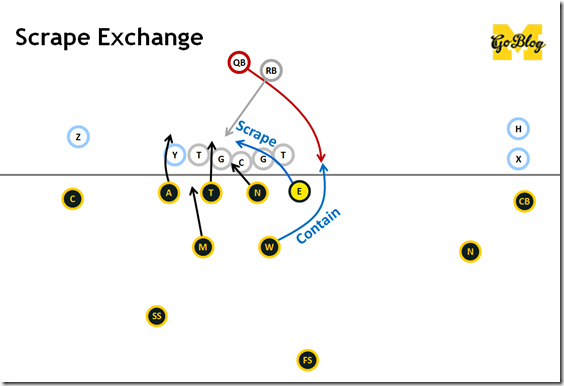

What’s a scrape exchange: It’s a defensive concept that flips the roles of two backside defenders, thus covering both sides of a quarterback’s zone read. The guy the offense thinks it’s optioning, usually a defensive end, “crashes” (move horizontally across the line of scrimmage) and is “exchanged” for another defender, usually a linebacker, who “scrapes” to the area the end vacated.

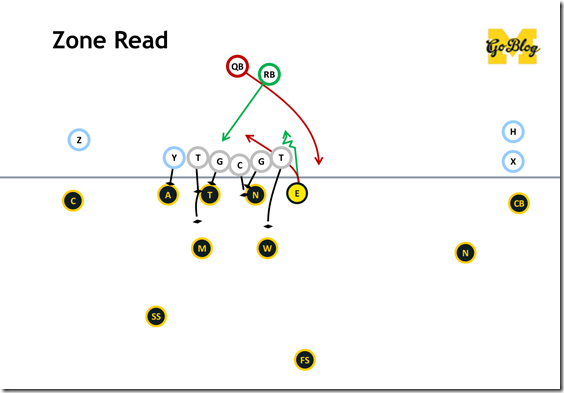

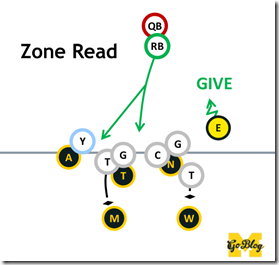

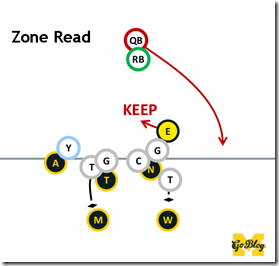

What’s it for? It’s the paper to the zone read’s rock. So you remember zone read:

This is the play that Rich Rodriguez invented to dawn the spread era. The offense leaves the backside defensive player unblocked and the quarterback options that guy. If the player (usually a defensive end) takes the opportunity of no blocker to scrape across to the running back’s path, the quarterback keeps it and runs into all the space left behind. If the optioned defender forms up to keep the quarterback contained, the running back gets the ball with the benefit of that extra blocker.

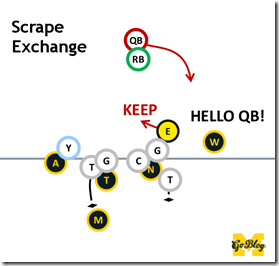

After decades there are lots of variations, but this is the gist of that offense. A scrape exchange makes the quarterback keep it, and makes that decision also wrong:

The quarterback running a zone read will see the defensive end crashing and keep the ball, only to find the linebacker appearing where the quarterback was about to run it. What the QB is expecting is on the left below; the result of the scrape exchange is on the right:

[After the JUMP: see it in action, and ways to beat it]

[Photo: Upchurch]

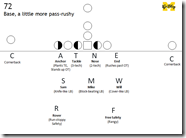

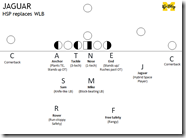

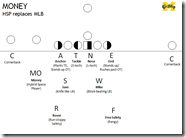

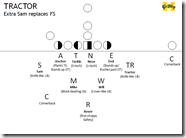

Last week we introduced the defensive terminology for Don Brown's base defense and his 4-lineman sub packages. Quick clicky-popup diagrams of the 4-3 and 4-2-5 forms we covered:

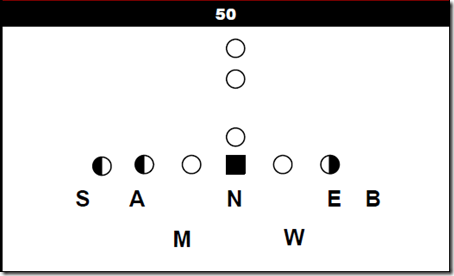

This week I'd like to get into the 3-4 and 3-3-5 and 3-2-6 looks, or in Brown's terminology, the "50" formations.

-------------------------------

SO WHAT DOES THE 3-4 LOOK LOOK LIKE?

The BC defense Brown brought over is a base 4-3 and 4-2-5 nickel, and they'll run a relatively small suite of plays from that base on most downs. But a lot of the fancy stuff—truly, most of the playbook—are out of what are usually called "30" and Brown refers to as the "50" fronts*, i.e. formations with three defensive linemen.

Here's the basic version, as taken directly from the 2013 Boston College playbook that James Light posted.

Technically, the "Tackle" (Hurst's position) has been replaced with a "Backer" (B). When you hear about a guy you thought was playing defensive end being called a "linebacker" (e.g. Kemp) it's possible he's playing the Backer position. If a dude's getting mentions as an "OLB" that's also a sign they're using him in that Backer/Sam role, where "Sam" means "Jake Ryan-esque."

That isn't anybody yet—I've been using Winovich as a placeholder—but the ideal here is clearly LaMarr Woodley: a 6'2/260-ish, athletic, stand-up, high-burst, space-tackling, strong-enough-to-stand-up-to-blocks attacker who can play rush end or cover some. That last is notable because it gives the 50 formations a suite of tactics that are generally absent from Brown's 70 formations: zone blitzes.

* [It's 50 and not 30 because look at the pic above and count the guys on the line. Now think back to that ol' Schembechler 5-2 "angle" defense. The more things change…

[After THE JUMP: bandits, canidae, diagrams that look like they're saying "Mike Gedeon" and "Will McCray", and blitzes. Oh lawdy do we got blitzes.]

23