math

[Ed-Ace: Brian (knee) is day-to-day, though he did prepare some content that will be posted this afternoon. Post-Burke-return hoops stuff and a Spring Game primer will appear later this week. In the meantime, enjoy some Mike Hart.]

In honor of Michigan’s all-time leading rusher’s birthday yesterday, a look at one of the unique careers in college football.

Since the 2011 season completed, I have been re-loading 9 seasons worth of games (6,063 to be exact) to update my database to include 2011’s new feature of Win Percent Added. In doing so, something immediately popped out at me. No running back added more wins to their team than Mike Hart did for Michigan.

Sometimes when you are looking at advanced stats you are surprised by how counter-intuitive results can be and sometimes you are surprised how well the data fits the existing narrative. Mike was the back who wouldn’t go down, always got the extra yard, killed the clock and never fumbled. Those are all the things that factor highly in Win Percent Added, especially the 4th quarter capabilities. Burning the clock in the fourth quarter is a key requirement of a successful running back. Especially a Michigan running back. No one did it better than Mike.

For his career, Mike Hart was responsible for 4.4 Wins running the ball. Reggie Bush edges him out if you count receiving WPA, as well, but those are tainted wins. It’s not just longevity and playing time that pushed him to the top. His per game average of 0.11 is fifth, behind two players with only a single season in the database and two more with two seasons at non-BCS level schools.

Freshman Season

At this point, writing about Mike Hart is a daunting task. What is left to write that hasn’t been written? He joined the team in the 2004 class as a 3 star recruit. He nearly set the national high school rushing record but wasn’t even the highest ranked running back in Michigan’s class. He would have been the fifth highest rated running back in Miami’s (YTM’s) recruiting class. He saw his first quality action in his second game of his career against Notre Dame in the second week of the season. By week three he was over 100 yards and posting a +5 EV+ and a crucial .36 WPA as Michigan held on for a 24-21 win over San Diego St.

Hart would go on to string together three straight 200 yards games in Big Ten play, including a 0.26 WPA in the Braylon Edwards game. His EV+ was always strong for a running back but where his EV+ was strong, his WPA was Herculean. Mike Hart made all the plays to win the game but none of them to lose them. By the end of the 2004 season true freshman Mike Hart had gone from anonymous three star to posting a per game WPA of 0.15, still my best recorded number in the Big Ten.

Sophomore Season

Injuries killed a large portion of the 2005 season. Kevin Grady, Max Martin, Antonio Bass and Jerome Jackson all took carries but none could come close to the production from Mike Hart. Kevin Grady was the only one to surpass a +1 EV+ in his absence, and that was mostly unnecessary against Indiana. Jerome Jackson did have a solid 0.14 WPA on 11 carries in an overtime win against Iowa, but that was limit of the success when Hart was out. In five full games of action Hart averaged 0.23 WPA which if replicated across an entire season would have given him the second highest (Reggie Bush, 2005) WPA average in a season for any running back since 2003.

It’s hard to think about what could have been with a healthy Mike Hart. Three carries in a seven point loss to Notre Dame, a DNP in a three point loss to Wisconsin eight ineffective carries in a four point loss to Ohio. There’s a very real chance he swings those three games and Michigan shares a Big Ten title with Penn State and spends its holiday taking on Florida State in the Orange Bowl rather than getting screwed over by the refs in the Alamo Bowl.

Junior Season

With fewer games coming down to key fourth quarter possessions in 2006, Michigan didn’t need the fourth quarter machine Mike Hart. He finished the season with a profile almost exactly like Chris Perry’s 2003 season. With not much in the way of close games, he didn’t have any massive, WPA pushing games like he had in his first two years, but 10 of 13 games would finish at .07 or better. For the year Hart ended at .09 WPA/game, his third top 20 Big Ten WPA year in as many tries. John Clay is the only player to have even 2 top 20 finishes.

Senior Season

For the second time in his career, injuries would derail an outstanding Mike Hart season. After surviving The Horror and somehow managing a strong WPA in the follow-up beating by Oregon, Hart was on track for a season to along side his junior year. An ankle injury in mid-season cost him a couple games of action and a couple more of effectiveness. 2007 would be his lowest rated season but still crack the Big Ten top 50. He would finish the year with enough quality carries to become Michigan’s all-time leading rusher and set the then non-existent WPA record.

Uniqueness

When I talk to people about how much more valuable quarterbacks are than running backs they usually point to running out the clock in the fourth as the unquantifiable equalizer between the two. When I first developed the Win Percent Added I was anxious to see how true it was. If you properly value the ability for a running back to keep the clock running and close out a game, what happens to the value relationship between quarterback and running back. After I crunched the numbers I found that the fourth quarter benefit was largely overstated. Until I looked at Mike Hart. There are very few running backs whose value is truly magnified by the little things like the narrative claims.

Mike Hart is the narrative.

Appendix

Mike Hart, Seasons

| Season | G | EV+ | WPA | Yards/Gm | Att/Gm |

| 2004 | 11 | 2 | 0.15 | 130 | 24 |

| 2005 | 8 | 0 | 0.14 | 84 | 18 |

| 2006 | 13 | 2 | 0.09 | 120 | 23 |

| 2007 | 9 | (0) | 0.06 | 129 | 25 |

Mike Hart, Games

| Year | Week | Vs | EV+ | WPA | Rush EV+ | Rush Att | Yards |

| 2004 | 2 | Notre Dame | (0) | (0.02) | (0) | 6 | 20 |

| 2004 | 3 | San Diego St | 5 | 0.36 | 5 | 25 | 121 |

| 2004 | 4 | Iowa | (2) | - | (2) | 23 | 98 |

| 2004 | 5 | Indiana | (2) | 0.05 | (2) | 18 | 79 |

| 2004 | 6 | Minnesota | (4) | (0.13) | (4) | 35 | 158 |

| 2004 | 7 | Illinois | 4 | 0.38 | 4 | 39 | 231 |

| 2004 | 8 | Purdue | 5 | 0.33 | 5 | 31 | 207 |

| 2004 | 9 | Michigan St | 3 | 0.26 | 3 | 33 | 224 |

| 2004 | 11 | Northwestern | 9 | 0.26 | 9 | 23 | 151 |

| 2004 | 12 | Ohio St | 2 | 0.05 | 2 | 15 | 59 |

| 2004 | 20 | Texas | 1 | 0.14 | 1 | 21 | 82 |

| 2005 | 1 | N Illinois | 5 | 0.17 | 5 | 19 | 117 |

| 2005 | 2 | Notre Dame | (1) | (0.02) | (1) | 3 | 4 |

| 2005 | 5 | Michigan St | (1) | 0.46 | (1) | 36 | 220 |

| 2005 | 6 | Minnesota | (1) | 0.06 | (1) | 27 | 111 |

| 2005 | 7 | Penn St | 4 | 0.34 | 4 | 23 | 114 |

| 2005 | 8 | Iowa | 0 | 0.01 | 0 | 5 | 18 |

| 2005 | 12 | Ohio St | (2) | (0.06) | (2) | 8 | 14 |

| 2005 | 20 | Nebraska | (2) | 0.14 | (2) | 19 | 74 |

| 2006 | 1 | Vanderbilt | 1 | 0.15 | 1 | 31 | 146 |

| 2006 | 2 | C Michigan | 9 | 0.17 | 9 | 17 | 116 |

| 2006 | 3 | Notre Dame | (5) | - | (5) | 17 | 124 |

| 2006 | 4 | Wisconsin | 1 | 0.03 | 1 | 23 | 91 |

| 2006 | 5 | Minnesota | 2 | 0.13 | 2 | 30 | 194 |

| 2006 | 6 | Michigan St | 3 | 0.08 | 3 | 17 | 122 |

| 2006 | 7 | Penn St | 3 | 0.12 | 3 | 26 | 112 |

| 2006 | 8 | Iowa | 1 | 0.10 | 1 | 31 | 126 |

| 2006 | 9 | Northwestern | (0) | 0.07 | (0) | 20 | 95 |

| 2006 | 10 | Ball St | 1 | 0.12 | 1 | 25 | 154 |

| 2006 | 11 | Indiana | 4 | 0.15 | 4 | 17 | 92 |

| 2006 | 12 | Ohio St | 5 | 0.09 | 5 | 23 | 142 |

| 2006 | 20 | USC | (3) | (0.09) | (3) | 17 | 47 |

| 2007 | 2 | Oregon | 3 | 0.09 | 3 | 21 | 127 |

| 2007 | 3 | Notre Dame | 5 | 0.11 | 5 | 26 | 187 |

| 2007 | 4 | Penn St | (2) | 0.06 | (2) | 44 | 153 |

| 2007 | 5 | Northwestern | (5) | (0.07) | (5) | 30 | 106 |

| 2007 | 6 | E Michigan | 7 | 0.30 | 7 | 21 | 215 |

| 2007 | 7 | Purdue | 3 | 0.11 | 3 | 21 | 102 |

| 2007 | 10 | Michigan St | (1) | 0.03 | (1) | 15 | 99 |

| 2007 | 12 | Ohio St | (2) | (0.06) | (2) | 18 | 44 |

| 2007 | 20 | Florida | (8) | (0.05) | (8) | 32 | 128 |

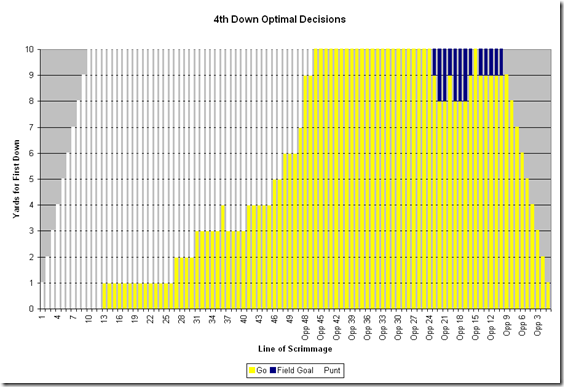

[Ed.: Bump. This makes sense to me: Michigan should mostly dump special teams once it gets across midfield.]

As Brian highlighted in the UMass round-up, maybe forgoing the punt altogether might not be such a bad decision. He noted my earlier look at the the topic and I wanted to pull it back and revisit and refine some of the work.

I looked at the years 2004-2009 and only looked at the top 20 rated offenses for each year. This study assumes that Michigan’s offense this year will be at a top 20 caliber and provides a broad enough definition of greatness that there is a good sample size. I did not distinguish what type of offense (Texas Tech Air Raid vs Georgia Tech triple option vs spread and shred) was used to get into the top 20. I will detail more assumptions as they are applicable along the way. In place of fourth down conversion percentages I used third down conversion percentage since the data pool is much larger and covers a wider variety of opponent levels. Since the thought process on a third down and fourth downs are roughly the same in most all (for now, anyway) situations, it seems reasonable to use the third down numbers.

Time for a you know what…

Assumptions: Top 20 offense, average defense, average punt game, average field goal kicker.

Based on these assumptions, except for long yardage, the punter should grab a seat once the offense crosses midfield. On your own side of the field the decision still makes sense starting around the 30 for shorter yardage situations and becomes more viable for longer yardage as you cross further down the field. Field goals become practical with 4+ yards to gain and only from about the 5-25 yard lines.

There are two big advantages a potent offense has that make 4th down tries more logical. The first is that they have more to gain by success. With a limited number of drives in a given game, why give them away for free? The second is that they are more likely to make them. Good offenses are more likely to be in better position on fourth down and more likely to make it. Here is a chart of great offenses fourth down conversions compared with all offenses. The right hand column was the one used for the above chart.

| To Go | All Teams | Great Off |

| 1 | 72% | 74% |

| 2 | 57% | 60% |

| 3 | 51% | 54% |

| 4 | 47% | 50% |

| 5 | 42% | 45% |

| 6 | 38% | 41% |

| 7 | 35% | 37% |

| 8 | 32% | 34% |

| 9 | 30% | 32% |

| 10 | 27% | 30% |

It’s not a huge advantage on any one given down, but Top 20 offenses convert the same opportunities about 2-3 percentage points more often than the average offense. Note: the rate of conversion for great offenses was much higher in the original analysis and is part of the reason the chart isn’t quite as go for it as the original.

But we don’t have an average <blank>

<blank> = Kicker

Let’s start with the kicking game, which is currently 5 points below average on the season and rated third worst in the country after the first three weeks.

Assumptions: Top 20 offense, average defense, average punt game, below average field goal kicker (FG make odds are reduced by 25% everywhere on the field).

The decisions near midfield obviously aren’t changed but now attempting a field goal on 4th and 5-9 from inside the 25 is no longer the most valuable option.

<blank> = Punter

I know it hasn’t been the most Zoltanic of starts for Will Hagerup, but at this point if he can hold onto the snap, there is no point in adjusting him to below average, even if he isn’t an advantage at this point.

<blank> = Defense

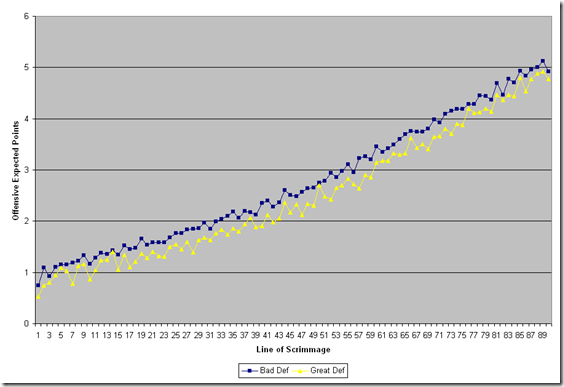

This is the one that seems a bit counterintuitive and Brian and I disagree on. I say that the strength or weakness of your defense is irrelevant to your offensive decision on whether or not try a fourth down conversion. My belief that it is irrelevant is based on this chart.

Great defense obviously give up fewer points than bad defenses but the key point is that the difference between a great defense and a bad defense is consistent up and down the field. Giving the opponent a first down at midfield isn’t a guarantee of a touchdown even with a bad defense and isn’t a guarantee that pinning an opponent deep against a great defense will keep the other team off the board. In fact, the gap between the two is about .25 points per first and 10 all the way from the 1 to the 90. If this is true, then the ability of the defense is irrelevant to the offense’s decision to go for it. For that to be the case, there would have to be evidence that the difference between a good defense and a bad defense changes at different points on the field.

So what does all this mean

If Michigan can maintain their feverish offensive pace this year and fail to find an adequate kicker, I think their decision set in all but late game score specific situations should look something like this:

As I noted previously, if you buy into this mentality, it opens up another opportunity, changing your early down play calling. If your four down strategy has changed, so should your down by down playcalling. It may become more viable to risk a wasted down with deep ball knowing that you have an extra, or it might just make sense to keep the ball short in the air and on the ground knowing that over four plays instead of three the likelihood of getting the yardages greatly increases so play to have the shortest possible fourth down attempt if you don’t convert before that.

24