zone running

The result [Fulller]

[Gif is here if you want to go frame-by-frame]

One of the hallmarks of a Harbaugh rushing attack is he finds ways to surprise defenders with blocks they weren't expecting. In the middle of 2016 Michigan brought out a weird play that pulled on the frontside like power but blocked zone on the backside. I started to draw it up, but it never really worked, and it disappeared from the offense until the first quarter of Saturday, when they ran it twice in a row. So let's draw it up.

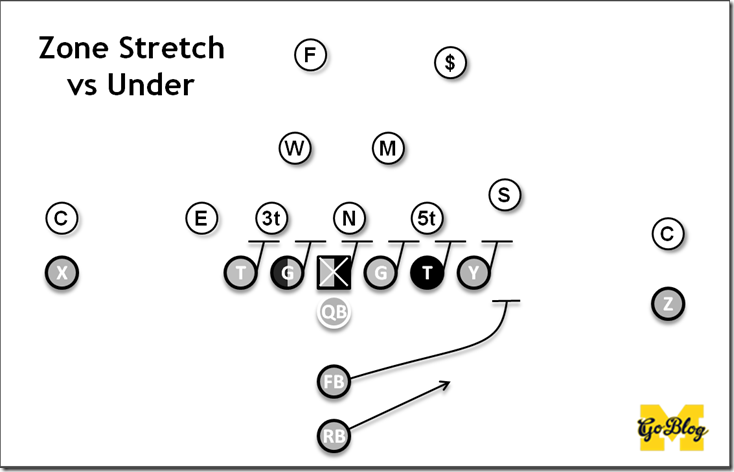

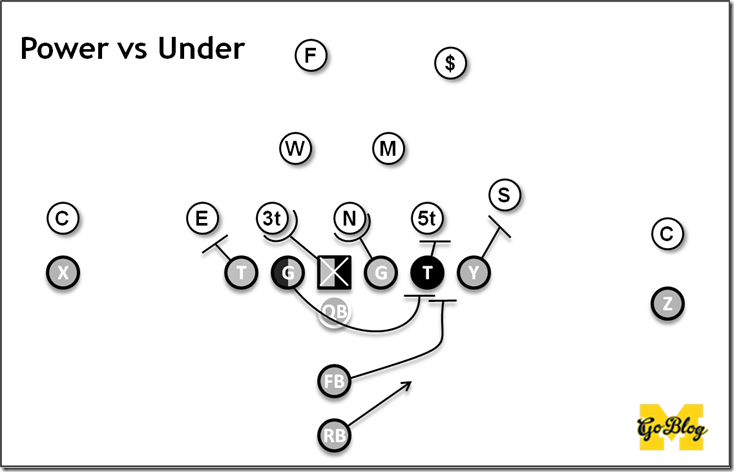

The play is a meatball gap run where the backside blocks like Outside Zone and the frontside uses a bit of Power. A quick refresher of what that means:

Outside Zone or Zone Stretch: In zone running you block whoever arrives in your gap. If you're "covered" (a lineman is lined up across from you) you have to make sure you deal with the guy over you, either blocking him through the play or combo-blocking him with the next lineman down (reading playside to backside) from you. If you're uncovered you can release to the next level, but if the lineman down from you is shaded playside on your buddy you can give your buddy some help first. OZ is the a more extreme type of zone. The OL are shuffling horizontally instead of trying to create space by shoving the DL vertically. Also Outside Zone doesn't block the backside end. Ideally your covered linemen will flank the guys they're over, and the uncovered linemen will release and get blocks on linebackers, but failing that you keep shuffling and waiting for the lineman to overpursue so you can lock him out of his gap. The running back and any lead blockers will pick their way behind this and wait for a gap to open up.

Power: The front side of the line each has a man to block, and your job is blow him down and seal him in whatever gap he's in so you can run through a preordained gap. Meanwhile the backside guard (usually) pulls around to thwack whatever linebacker or whatever shows in that gap, and maybe you also send a fullback escort. The idea here is to give you advantageous blocks by "blocking down" on dudes lined up further from the play than you, and "kicking out" the last dude to the playside to make the gap you're running into as wide as possible. The running back then follows a mass of bodies into the gap.

[After the JUMP: These are entirely different concepts and I don't understand how they can work together]

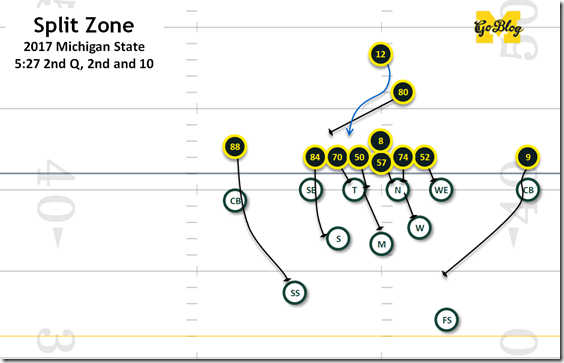

There was a rather long twitter exchange earlier this week between BiSB and former player/regular MGoBlog reader Jon Duerr about this play, a ho-hum split zone that Michigan State swarmed. Both guys saw things in this play that somewhat characterized the Spartans’ approach this game, and why Michigan had to pass to counter it. So I thought I’d draw it up.

THE PLAY:

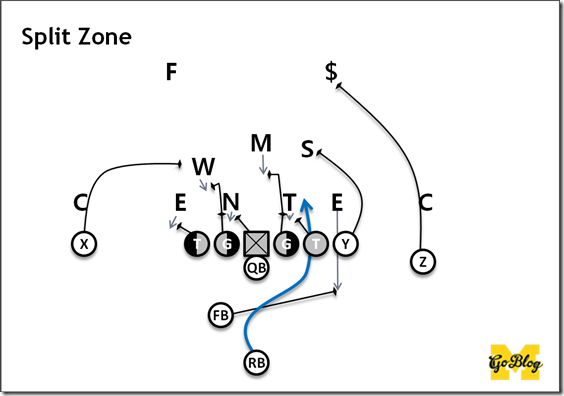

This play has been an effective counter to the base inside zone run all year. Rather than making the tight end block the DE lined up over him, the TE releases into a linebacker, leaving that end to get clobberated by a crossing TE or FB. Defenders who think they’re trying to defeat zone blocks to the frontside suddenly find themselves sealed in place, and linebackers who thought they were flowing to frontside gaps are just putting themselves in position to be blocked by free-releasing linemen who shouldn’t have an angle on them:

Regular zone rules are otherwise in effect. The covered linemen and the next closest uncovered linemen will try to combo the DTs then work their way to the Mike and Will linebackers. With split zone however play is designed to seal the tackles—who think they’re winning at preventing themselves from getting reached—in place and release the covered guys to the linebackers, who will naturally try to flow to the frontside of those blocks. Then—“whoops”—the linebackers are on the wrong side.

What you do with your receivers is up to you (and what your opponent is doing). The tight end’s crack block on the SAM is mirrored by the split end (X)’s attack on the Will, which mimics a mesh play. Michigan added the flanker (Z) cracking a safety rather than running off a cornerback, since the CB might take himself out of the play by playing man anyway.

Michigan State snuffed it out by playing super-aggressively against the run. They’re doing three things to blow this up.

[After THE JUMP]

----------------------

Hello, this series is a work-in-progress glossary of football concepts we tend to talk about in these pages. Previously:

Offensive concepts: RPOs, high-low, snag, covered/ineligible receivers, Duo, zone vs gap blocking, zone stretch, reach block, kickout block, wham block, Y banana play, TRAIN

Defensive concepts: Contain & lane integrity, force player, hybrid space player, no YOU’RE a 3-4!, scrape exchange, Tampa 2, Saban-style pattern-matching, match quarters, Dantonio’s quarters, Don Brown’s 4-DL packages and 3-DL packages, Bear

Special Teams: Spread punt vs NFL-style

------------------------------------------

We’ve been using this offseason to learn about some of the tools in Harbaugh’s inside running game toolbox, and have so far neglected one of my favorites: Split Zone. This play today is a mainstay of Rich Rod’s offense and its derivatives, since the blocking is almost exactly the same as a base inside zone read right up until the guy who thought he was forming up to play an option gets blindsided by a large, laterally moving TE.

But it originated in under center two-back offenses, and remains an important curveball for I-form teams like Iowa, Wisconsin, and Michigan State. If you’re going to be running inside zone, like, at all, and you’re not in a 4- or 5-wide formation all the time, you probably run this play and variations on it at least 3 or 4 times a game.

Let’s draw it up.

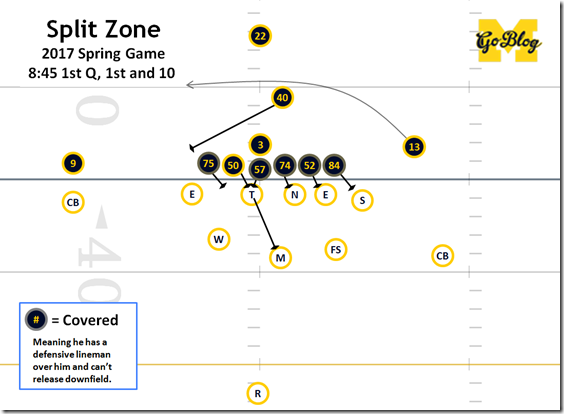

ignore McDoooooom—he’s just there to get the fans yelling “McDooooooom” and distract from what’s really going on

No, that line from the “T” to the “M” isn’t Hurst blocking Devin Bush—it means the guard and center will combo the the DT and the middle linebacker. This is true for most zone plays so I might just start drawing things up this way from now on.

This particular example from the Spring Game had some motioning and a fake jet, and the defense threw a few curveballs at it that the blocking handled as they were supposed to. We’re going to ignore those for now then come back and discuss them later when we’ve established the basics of what’s going on here.

How it works

Split zone is a riff on inside zone but flips the attack order: rather than reading outside-inside-backside like on most zone plays, Split Zone wants to hit that north-south cutback lane first, only going to frontside gaps when that’s not available. They do this by flipping the backside blocking tree, so that all of the usual gaps defenders think they’re going to be defending are not really the gaps they’re defending. That leaves an unblocked backside defender who gets whacked by a catchy-blocky fellow coming from the other side of the backfield.

Its strength is that at first blush it’s inside zone, which threatens a bunch of gaps to the strongside, with a backside cutback. But split zone is attacking the backside first, leaving the frontside gaps as a Plan B.

looks like inside zone

The key difference occurs with the backside blocking. Rather than kicking out the EMLOS (end man on the line of scrimmage), the backside OT will ignore the edge and check the gap inside of him, moving downfield if nobody shows. The backside guard and center are still going to combo the nose tackle, but they’re trying to get around the opposite side, so a nose tackle who tries to get to the frontside of the center is just putting himself in the wrong hole.

Now for the kicker. Remember how we left that EMLOS on the backside unblocked, right where the play design is going? Don’t worry we’ve got a plan for him: a fullback or tight end should be coming across the formation, then using that latitudinal head of steam to bang open the hole (the orange block in the above gif).

If the offense is lucky, the defensive end, upon realizing that the tackle inside him isn’t trying to kick, will think he’s getting optioned and form up outside to force a tough read while the middle linebacker fears play-action and stays back to read the backfield action.

[Hit THE JUMP for what happens when they don’t get lucky]

30