doug nussmeier doesn't have enough tags yet

Fuller

This is a companion piece to last week's refresher on inside zone, Michigan's new base play. Outside Zone, also known as the Zone Stretch, is one of two very common complementary plays to IZ, because the technique for the offense isn't very different, but the way the defense has to defend it is (the other complementary play is Power-O, Michigan's extremely nominal base play the last few years).

OZ Resources: Smart Football, Roll Bama Roll, FishDuck (Oregon), BTSC (Steelers) Mile High Report (Denver Broncos), how to Mike.

Outside Zone Defined

The difference, as made obvious by the name, is the point of attack. Inside Zone blocks "downhill"; the running back aims for the first line defender past the center, and picks a lane to either side of the guards. In Outside Zone the back is running to a point outside the five linemen. Some coaches say run to the back of your tight end, others say run to the end man on the line of scrimmage (EMLOS); it comes to the same thing.

Here's Alex Gibbs (from the Elway-era Broncos), via Smart Football:

This is another "base" play. If the defense plays sound against it, the success of the play comes down to execution and talent. As with IZ, if the defense gets too aggressive the reaction to that is built into the play.

This isn't a play that attacks multiple sides; it threatens outside and can come back inside if the defense overreacts to that. Since we're coming into this from a fan perspective I won't get into the footwork you can't see, but you'll recognize Outside Zone immediately because the linemen start out by moving sideways.

As you can see, reps, reps, and more reps turn this into a possibly devastating play. The more you run it, the better the team will react to various things defenders do. In the video above Gibbs talks about the guards "making the read for him [the RB]". The big breaks from OZ come when a guard or center sees a defender reacting too aggressively, let that guy run himself out of the play, and then destroy a back-filling defender.

Recognize Alignment

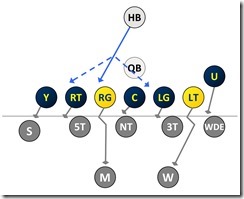

Like inside zone, the offensive linemen have to read the defensive front to decide before the play begins who they're blocking. The "covered" rules still apply: if someone's lined up over you, you're covered; if not you're uncovered:

The general rule of coveredness still applies: if there's a guy lined up over you, you have to block him. But the whole idea of a zone stretch is it slides the line, so if you're uncovered that means you have to reach the next defender to the playside of you, and if you're covered you're looking to 1) get playside of that dude and 2) combo block him with your uncovered buddy, and 3) release and get downfield.

Combo Blocks

Combo blocking is one of the things that takes lots and lots of reps. The essential blocking rule is don't let anybody cross your visor, and block the guy in your zone. Outside Zone's strength against a base defense is it creates double-teams at the point of attack

How It's Defended

Outside Zone pairs well with Inside Zone because a defense used to IZ can get caught inside, but that should be rare with a well-coached defense because the play is quite obvious from the first step by the offensive linemen, and from what's going on in the backfield (the RB isn't coming downhill). As soon as the defense realizes this they have to get on their horses and prevent the offensive linemen from flanking them, but because of the threat of the cutback, the defense also has to maintain gap responsibility.

There's gonna be a huge temptation for the EMLOS, with the play headed right for him, to square up and end the play right there, but the most important thing (unless they've given him extraordinary safety help) for him is to keep the play inside. The offense knows this, and a good tight end who can get that EMLOS skating wide can create a big hole to run through; a bad tight end will let the EMLOS get leverage and hold him inside, squeezing the hole shut.

Keys to Success

Every little thing the offense does has a potential to make or break this play. The faster the RB makes his cut and accelerates through the decided hole, the bigger this can break.

A fleet-footed, quick-thinking, tough sumbitch of an interior lineman can really make this go. David Molk could consistently get playside of a guy lined up shaded strong on him, and could react so well to defenders that he'd often make the RB's job easy, abandoning a defender running himself out of the play to catch a chasing linebacker and create a gaping hole.

Outside Zone is where a great running back can really shine and a just-a-guy can make the play barely more than a side show. Mike Hart, with his great vision for a developing hole, his super-quick and decisive cut, his great acceleration, and his tiny stature in comparison to the mountain of flesh in front of him, was an awesome Outside Zone running back; if only he had stayed healthy the one year he got to run it consistently.

[One sample play and more coming, after the jump]

By the end of this article you should be able to make an educated guess

as to what Braden is saying to A.J. Williams [Fuller]

You may have heard Michigan has a new offensive identity, by which of course we mean Michigan now has an offensive identity. We think. We're told. Evidence for this is Michigan hired a new OC who runs inside zone, and he has even Brady Hoke talking about it being our base thing. This thing is totally happening. I mean if they hadn't sworn up and down for three years that Power was going to be their thi...

Let's just not go into that and focus on inside zone and how to watch inside zone, and how to be correctly disappointed with the correct person when inside zone isn't run very well. Since this is a new thing, and the offensive line are all relatively new things themselves, and the recent history of Michigan football has given you no reason to believe otherwise, and there are some really good defensive linemen Michigan has to go against this year, let's concede right now that Michigan isn't going to be running inside zone very well this season, especially early. Let's pretend like the coaches are going to stick it out anyway and let it play out.

IZ Resources: As well as the above-linked articles, I drew from Chris Brown at Smart Football, and this article that quotes Chris Brown on a Philly Eagles website. And Space Coyote wrote an entire article on IZ and some plays that stem from it in this year's HTTV; I'm sure he'll pipe in as soon as I mess something up here.

|

| Every blocker is responsible for whatever defender appears in the "zone" he's responsible for blocking. |

A Temperate Zone

What's inside zone? Maybe it's best to start with what it's not: man. In MANBALL, most linemen have an assigned guy to block; a lead blocker (sometimes a puller) is the only dude who has to make a tough, mid-play decision, and the running back just has to follow that guy.

Inside zone is a base running play where all the blockers are reacting to the defense, not just a lead guy, and the running back has to choose from among various holes that could open up. It takes a different set of skills, mastery of a different set of blocks, and most of all: reps reps and more reps so that everybody can make split-second decisions and those decisions will be correct.

That's not to say all decisions are made after the snap. In fact most blocking assignments are determined by how the defense is lined up. In many cases it won't be all that discernible from man-blocking.

yellow is uncovered. click bigginates.

The read OL have to make is whether they're "covered" or not. Covered means there's a DL lined up across from you. If there isn't, you are "uncovered" and most likely you'll get to go hunting linebackers. But first you look next to you and see if there's a defender shaded to the playside of your buddy; he may need help with that lineman before you release downfield. If that defender is a beast your buddy may need all the help he can get. You deal with the first level defenders before you worry about stopping linebackers.

Almost always, more than one defender will arrive in a blocker's zone. So zone blocking means lots of shared blocking. Ultimately the blocking ends up being 2-on-2 instead of 1-on-1. For example in captioned illustration above-right, the center and right guard are together responsible for blocking the nose tackle and the middle linebacker.

Footwork Impeccable

Offensive linemen in high school seldom get the right footwork down. Zone-blocking footwork isn't the same as pile-driving some dude, for one; and two it's not something many high school coaches know how to teach; and three if you're a 6'6"/300 future Big Ten OL and your job is to block a 6'0"/180 future Big Ten economics major, your greatest motivation to pay attention to your feet is probably the preservation of your prom date's.

In this moment it matters greatly. You need to get off the snap, get playside of your defender, get downfield, and get your feet set beneath you, your hands inside, and your pads beneath his so you can ride him out of the play, stonewall him, or shove him downfield; you let him dictate his fate.

On inside zone, an uncovered guy's first step is always to the play-side, not directly toward the guy you're going to block (the OL taking this step is a good indicator it's a zone-blocked rather than man-blocked play). This is because the DL don't always come straight upfield; you don't want them running by you.

Your job is to block the guy trying to cross you. If someone lined up inside you and ran further inside you, he's not yours. Your head stays downfield until you lock on a target, and any object that attempts to cross your field of vision must be stopped.

That Rabbit's Dynamite

Interesting example of a 1) a cutback and 2) the U starting on the strongside of the formation then executing his backside block almost like a lead blocker

Mastering the combo blocks and footwork to respond to all the things defenses throw at you takes a bazillion reps. The upside: inside zone, like option offenses, is a multi-attack threat that can go where the defense doesn't. A called IZ play could end up going outside, or inside, or cut to the backside depending on how your opponent defends it. A well-run IZ offense doesn't let defensive fronts play aggressively; if they want to stop you they'll have to activate the safeties in the run game, opening up the pass. It's not wimpy; it's smashmouth football that—as you'll see—relies mostly on crushing blocks to break things big.

[After the jump I'll show some sample executions versus various defensive alignments so you can get a sense of how it attacks and what factors lead to its success.]

Fuller

Question: Did you notice any appreciable difference in the Spring Game between the Borges offense and Nussmeier's? What are hoping to see by fall, and do you think they appeared to be heading in that direction?

Ace: Well...

I might not be very useful in this roundtable.

--------------------------

Brian: Well... it wasn't much different in person.

And the stuff they did show was the usual vanilla business that is designed to be as basic as possible, so I'm not sure there's a whole lot to glean. It looked a lot more compact than last year's offense, sure. All spring games look compact as the bells and whistles are stowed away for use on a two-point conversion in the bowl game after you're down one billion points.

Michigan did seem to have a dedication to the inside zone with a side of power, and the linemen seemed more focused on making sure the defensive tackle was good and beat up before trying to get to the second level. That led to a lot of runs that made it to the line of scrimmage (hooray!) and didn't get much further. And that's fine. You don't dig out of a hole as big as the one Michigan's in quickly. Michigan looks like it's going to be mostly an IZ team that mixes in power to keep opponents honest, and as long as they look like that through the nonconference season and don't start flipping people about all willy-nilly, that is the first step towards competence.

So that's what I think we'll see: a boring-ass offense that tries to keep errors to a minimum and punts a lot. People will complain about its predictability and simplicity and they'll be right. Michigan doesn't have much choice, unfortunately.

--------------------------

Seth: It's impossible to compare Borges's Michigan offense to anything, because Michigan's offense wasn't anything under Borges for more than a few games. The three things I was looking for were 1) personnel, 2) a concept, and 3) how well those things could complement each other.

|

| If you flup this up, Doug, so help me Bo… |

Personnel was heavy, which was discouraging. For one Michigan has little in the way of tight ends. I didn't see anything from A.J. Williams, who was behind Heitzman, or Khalid Hill, who was behind Houma, and that was discouraging for hope of TE production before Butt's back. Houma is a fullback who lined up at the U only to motion back to fullback.

The operating theory on the OC hire was that Nussmeier at Bama was forced to use heavier formations than he wanted, however that compromise came down to 65% of snaps with three or more receivers:

| Team | Big | 2 WR | 3 WR | 4 WR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bama (Sugar Bowl) | 3% | 31% | 58% | 7% |

| Michigan 2013 | 8% | 54% | 29% | 9% |

| Mich 2011-'12 | 7% | 41% | 43% | 9% |

| Mich 2008-'10 | 1% | 7% | 76% | 15% |

Eyeballing it, the spring game was closer to Michigan in 2013. If there was a difference it was more Ace as opposed to I-form, but that's less relevant because those second TEs were usually Houma and Kerridge, i.e. the fullbacks. There's a fear shared by every Michigan fan with a functional nervous system that the run-and-shoot-yourself-in-the-face offense under Borges was, despite protestations to the contrary, a mandate from the top. If Nussmeier compromises for Hoke more than he would for Saban, well, that would be insane. If that was all just a bunch of spring practice hooey, well, why are they spending spring practice on hooey when every countable hour is precious?

|

| Great scott Doc, this is too heavy. [Fuller] |

On the upside, there was a concept. The running was mostly zone, with some power mixed in only because you need to pull somebody to sell play-action. The passing game was a slight departure from Borges, who used a lot of 5-step patterns last year. These were 7-step patterns with an outlet, matching what we saw from Nussmeier at Alabama. The difference here can be overstated; Borges used lots of longer routes with Denard but went to the quicker stuff in 2013 because he couldn't get protection to last longer than that.

How do I feel about that? Well it fits the receivers' abilities. There's no Gallon to turn every 7-yard cushion into an easy 5 yards, but there's Canteen and the Funchise and lots of leapy things who can reel in a desperation heave. I have serious doubts the offensive line can hold up that long, but that's why there's an outlet. On the play I drew up it was Funchess running what appeared to be an option route; with Alabama it was usually an RB.

Zone is good. It's what Funk knows, it's easier to teach to young linemen, and we've already established his charges' total inability to pull correctly. My guess is the tight ends are in there because the OTs need help, though any time you have Heitzman/Williams/Houma in there instead of Chesson that's a talent downgrade.

I think the great hope for an offense that can finish in the top half of the conference is Gardner. I think Nussmeier is building an offense that is simple for everybody but him.

23