picture pages

[Bryan Fuller]

You're going to have to bear with me on the offensive UFRs this year. The last time I saw a traditional gap-blocked, regular-ol-QB offense for anything more than a one-game debacle was ten years ago. That was the first year I did UFR and most running plays of that sort were deemed "another wad of bodies" because I didn't know what I was looking at. Since then:

- Two years of Debord running almost nothing but outside zone

- Three years of Rodriguez running inside and outside zone with a little power frippery

- Two years of Hoke trying to shoehorn Denard Robinson into a pro-style offense, giving up, and running a low-rent spread offense

- Al Borges's Cheesecake Factory offense that ran everything terribly

- Doug Nussmeier's inside zone-based offense.

I've seen plenty of power plays. Most of them were constraints that could be run simply and still succeed because the offense's backbone was something else. The rest were so miserably executed that they offered no knowledge about what power is actually supposed to look like. I watched a bunch of Stanford but not in the kind of detail I get down to with the UFRs.

![fbz3gg1_thumb[1]](https://mgoblog.com/sites/mgoblog.com/files/images/655ca1995608_CE7E/fbz3gg1_thumb1.png) One thing that I am pretty sure I think is that the popular conception of power as a decision-free zone in which moving guys off the ball gets you yards is incomplete. Defenses will show you a front pre-snap. You will make blocking decisions based on that front. Then the defense will blitz and slant to foul your decisions and remove the gap you want to hit. If you do not adjust to what is happening in front of you then you run into bodies and everyone is sad.

One thing that I am pretty sure I think is that the popular conception of power as a decision-free zone in which moving guys off the ball gets you yards is incomplete. Defenses will show you a front pre-snap. You will make blocking decisions based on that front. Then the defense will blitz and slant to foul your decisions and remove the gap you want to hit. If you do not adjust to what is happening in front of you then you run into bodies and everyone is sad.

What Stanford was great at was running power that was executed so consistently well that it was largely impervious to all the games defenses played. This requires linemen who are downblocking to think on their feet, maintain their balance, and stay attached to guys who may be going in directions they were not expected to. It requires everyone off the line of scrimmage (tailback, fullback, pulling G) to see what's in front of them and adjust accordingly.

Michigan did a bad job of this against Utah. They also got blown backwards too much, complicating decisions for the backfield. The latter was not a problem against a much weaker Oregon State outfit. The former was much better, and that's the most encouraging thing to take from this game.

Here's an example. It's a six yard run in the first quarter on which Oregon State sends a blitz that Michigan recognizes and thwarts. There's no puller on this play; I think it was intended to be a weakside iso that ends up looking not very much like iso because Michigan adjusts post-snap.

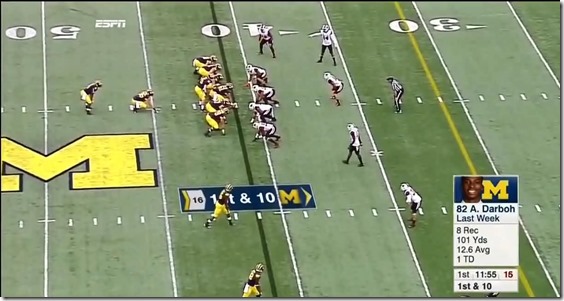

M comes out in an I-Form twins formation; Oregon state is in a 4-3 that shifts away from the run strength of Michigan's formation. They are also walking a DB to the line of scrimmage:

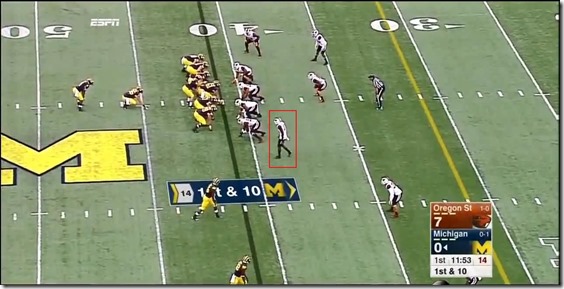

By the time Michigan snaps the ball this DB is hanging out in a zone with no eligible receiver while both WRs get guys who look to be in man coverage. This is not disguised well unless the highlighted player is Jabrill Peppers and can teleport places after the snap:

He's going to blitz and the DL is going to slant to the run strength of the line. Michigan will pick this up, and I wonder if they IDed the likelihood of this pre-snap. No way to tell, obviously.

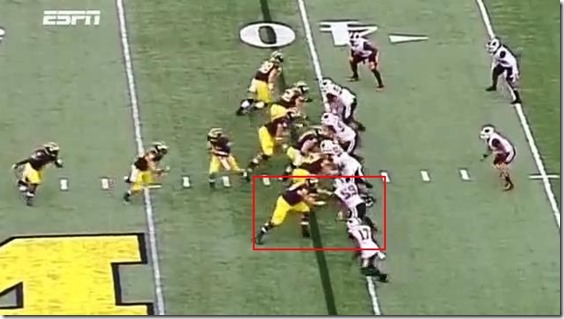

On the snap both the FB and RB start to the weak side of the formation; you can see Erik Magnuson start to set up as if he is going to execute a kickout block on the defensive end:

With the blitz and slant from the Oregon DL that's not going to happen. Each Oregon State DL has popped into a gap. Kerridge is taking a flight path to the gap that would normally open between Magnuson and Kalis, the right guard, on a play without this blitz. Without the blitz the DE would be the force player tasked with keeping the play inside of him; Magnuson would have a relatively easy job as he and the DE mutually agreed on where he should go.

Here the DE threatens the play's intended gap. Magnuson can't do anything about that. The D mostly gets to choose what gap they go in, and it's up to the offense to roll with the punches.

Michigan does this:

A moment later Magnuson has changed his tack from attempted kickout to an attempt to laterally displace the DE using his own momentum. Kerridge has abandoned the idea of hitting the weakside B gap and is flaring out for the blitzer.

Thunk:

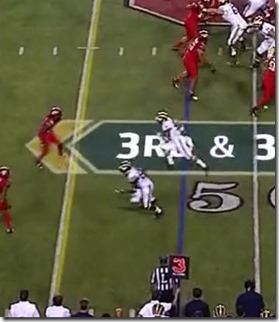

Now, this could be successful for Oregon State still. The slant got five Michigan OL to block four guys. Nobody got downfield; the slant got a 2 for 1. But their MLB has stood stock still for much of this play, and Magnuson ends up shoving his dude past the hash mark—+1, sir. This is a ton of space to shut down, and De'Veon Smith is the kind of back that can plow through you for YAC.

Smith fends off the linebacker with a stiffarm and starts gaining yardage outside; it could be a good deal more but Chesson misses a cut* and the DB forces it back, creating a big ol' pile:

Second and four sounds a lot better than second and eleven.

*[Drake Harris will later pick up a 15-yard penalty for a similar, but more successful cut block; the genesis of that flag is probably Gary Andersen doing some screaming at the official after this play.]

Video

Slow:

Items of interest

You don't get to pick the gap even if it's gap blocking. Defenses slant constantly, and often in a specific effort to foul the intended hole and pop the back out into a place where an unblocked guy can hit. Post-snap adaptation is a must for a well-oiled power running game.

Slants win if they suck away an extra blocker. I would be peeved at the MLB if I was Oregon State UFR guy. While Michigan adapts to the slant well enough to provide a crease for Smith, the blitz means Michigan had to spend a blocker on the defensive back and the MLB is a free hitter. He should be moving to this more quickly than he does.

Slants also tend to open up giant running gaps. Adjustments like the above will often lead to a defender running in one direction suddenly getting unwanted help from an OL. If the OL can redirect and latch on just about everyone is going for a ride here. Once Magnuson locks on and Kerridge targets the DB these are two blocks that are easy to win and Smith is going to have a truck lane.

Given how much space Smith has even a linebacker playing this aggressively who shows up in the gap might lose or get his tackle run through; Michigan's getting yards here, whether it's three or six or more if Chesson gets a good block.

In the past this site has seen arguments about whether meeting an unblocked safety at or near the line of scrimmage is a win for the offense or the defense. I have largely come down on the side of "that absolutely sucks," but when the hole is so big that the defender is attempting to make an open-field tackle it's a lot more appealing.

Michigan WRs need to be more careful with the cut blocks. You can cut a guy from the "front," by which the NCAA means the area from 10 to 2 on a clock. (Seriously, that's the way it's defined in the rulebook.) This was very close to a flag, and Michigan got one later.

I wish Michigan was running pop passes, as those are good ways to get defensive backs hesitant about running hard after plays like this. Maybe in a bit.

Despite some post-burial kicking at the ceiling, Jake Rudock's pick six was the final nail in Michigan's coffin against Utah. It came on a route that I've called a "circle" for a bit now. The idea is that you run a slant, then abort that halfway through into an out route. Corner jumps the slant, you get some nice separation and hooray beer. Or you run an out, corner jumps the out, etc.

The general idea is that it is a horizontal double move. I've called it "circle" probably because NCAA football did back in the day; you can see that on a successful one the WR does tend to run in a little circle after his first break:

Both Utah and Michigan tried to run these routes on Thursday, with different results. Here are those plays… AT THE SAME TIME.

On the left will be a Utah throw on their first touchdown drive. It's second and six; Michigan is in the nickel they ran the whole day, showing press coverage on the outside.

On the right, Michigan attempts to convert a third and three halfway through the fourth quarter while down a touchdown.

As far as we're concerned these plays are completely identical to start: we are looking at the slot receiver to the bottom of the screen with a corner who is locked up in man coverage three yards off the line of scrimmage.

A couple moments after the snap both WRs have crossed the LOS; the only difference in the corners is that the Utah guy has taken a step forward, perhaps anticipating this route.

[After the JUMP: everything goes fine because HARBAUGH? Probably!]

Michigan's run game started out with a thud, with a series of short gains and even the occasional Dread Pirate TFL rearing its ugly head. As with the Notre Dame game, the problems due to were a mélange of errors from lots of people. And as you might expect against Miami, most of them were mental issues.

People have asserted that Miami was dropping an eighth guy in the box and that guy was blowing up the Michigan run game. That's simplistic; these days spread-oriented offenses are looking at one or zero deep safeties on every play. The eight man box is something you have to deal with as a coach, and anyway when you're playing Miami it shouldn't matter.

Michigan's issues were largely assignment-based, with the occasional bad block thrown in; the tailbacks were better but still had issues. The nice thing is that as the game went along we saw Michigan correct some of those those problems and start moving forward. Mason Cole in particular was evolving right on the field, hampering two plays with errors and then executing in near-identical situations just a few minutes later. One was mostly executing a block; this one was about IDing the guy he needs to address.

Which Guy Needs Help? Not That One.

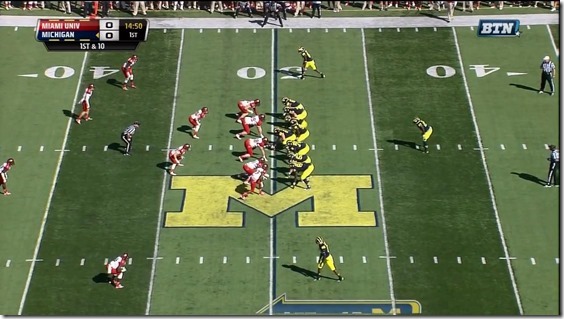

This is actually the first play of the game. It comes from the 50 after the least interesting successful Dennis Norfleet kick return ever (run to the right until the kicker stops you), and Michigan comes out in an ace set. Miami has a 4-3 under on the field (sort of; their SAM is 190-pound Lo Wood) and will roll a safety down for guy #8.

Michigan's going to run inside zone and things are going to go pretty well all over the field with the exception of Mason Cole and AJ Williams trying to handle the backside DE.

This is your presnap setup:

There's a one-technique NT and a five-tech SDE. The SDE is splitting Cole and Williams down the middle, and the play is going to the top of the screen. It is very hard for backside blockers to do anything with a guy who is 1) lined up playside of him when 2) they get no help. This is about to happen to Williams.

I'm not entirely sure why this guy is free to fly down the line and blow this play up. The other DL are handled by Michigan's OL driving guys lined up a half-step to the playside of them. It seems like he figures that the OLB is going to be there to clean up anything that breaks behind him, so gap integrity is for suckers. (Michigan will get a bunch of waggles off this tendency, as Miami isn't using that OLB to contain hard upfield.)

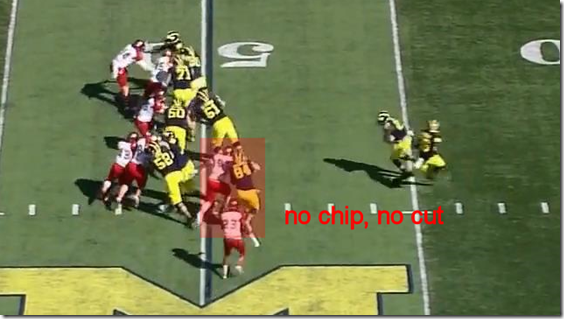

On the snap Magnuson hops over a half-gap to get the nose; Cole goes to his zone a gap over without touching anyone and then starts helping on Magnuson's block. Williams is going for this DE:

Williams does not get the DE even a little bit, and with Miami DL set up to the outside on the frontside of the play Green is correctly going right up the gut, something that looks promising as Michigan gets movement on the DL.

The problem:

Williams was put in a tough spot here; even so this feels substandard. Annoying the guy, pushing him so that he's on the correct side of the LOS, maybe cutting him: all of these things are better than escorting him to the RB.

A yard later it's clear that Michigan has cleaned out the DL; one linebacker shot a gap and is going to help tackle here but without the space constriction provided by the Williams block-type substance shooting that gap is a dangerous game to play that is 50/50 to put the tailback one on one with the safety for all the yards.

Green falls forward for two as Magnuson finishes pancaking the NT. Cole ended up not really doing much of anything on the play.

Video

And the slow version:

[After THE JUMP: something that goes better]

63