Sports Economists: Always Wrong About Everything

The last straw for Run of Play proprietor, Slate contributor, and Dirty Tackle blogger Brian Phillips were two articles on consecutive days citing Franklin Foer's assertion that dictatorships led to good soccer. Many of the nations that have been super good at soccer over the years have been run by dictators if you lump Vichy France in with them and think Hitler and Mussolini have anything to do with anything in the 21st century. The first problem with this piece of intellectual noodling is that the percentage of teams who have won the World Cup during or after a period of dictatorship (86%) is almost equivalent to the percentage of countries that have undergone periods of dictatorship since 1930. Twenty-five of the 32 teams in this year's edition have done so, 78%.

The second is that the statement means nothing. Phillips on the Kuper/Szymanski book Soccernomics, which endeavors to be a Freakonomics for the beautiful game:

You want to say that money is the secret behind soccer success, so you break down international games by GDP and find that, yeah, it matches up fairly well. But it doesn’t work as a theory, because China is terrible at soccer and the US is only okay at it. So you invent a variable called “tradition” and add it into the formula, which helps (now Brazil’s looking really strong), but you’re still left struggling to explain why, say, England doesn’t do better. So you add in population size, and on and on and on. Eventually, you have a delicately balanced curl of math that correctly reproduces the results of most recent matches (even if it accidentally predicts that Serbia will reach the current World Cup final). So you go to a publisher, but no one wants to buy a book about how GDP is covariable with national-team success 40% of the time, or whatever; they want a book that claims to have Uncovered the Secrets of Soccer© Using Funky Mathematical Techniques™. And so you’re led into making grand claims for the predictive power of research that really only demonstrates correlation. And there’s enough data swirling around a complex event like the World Cup that you could get the same results by collating fishing exports, number of historic churches, and percentage of authors whose names include a tilde.

You have no mechanism. Your correlation is extraordinarily weak. You have just wasted everyone's time.

The very same day, Slate (et tu!) published an article by a guy who studies a particular brain parasite claiming a correlation between soccer performance and infection rates of Toxoplasma gondii, a bacteria whose raison d'être is to get in a cat's stomach so it can make babies. An R-squared was not mentioned, but it was gestured to. Regression rules everything around me. This is why most published research results are false.

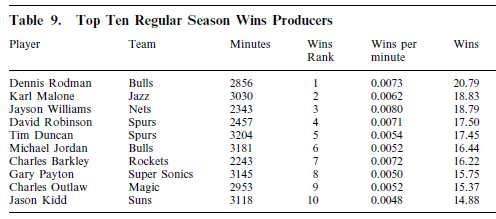

Soccer is not the only sport suffering from pseudoscience obsessed with elevating correlation above all else, mechanism be damned, and elegant curls of math that prove little other than the academic's talent for obfuscation in the name of publishing. Kuper and Syzmanski actually got to the party late. Princeton economist and Malcolm Gladwell fave-rave David Berri's been here for years, and he's packing the platonic ideal of delicately balanced curls of math that end up ludicrous on further inspection. Behold the best (and sixth-best) players of the 1999 NBA season:

the emperor's clothes are fine indeed.

Berri made a splash in the sports world when he released a transparently silly book that purported to show that Dennis Rodman was responsible for more wins than teammate Michael Jordan. This drew the ire of the basketball statistics community and anyone with a damn lick of sense. People set about showing that Berri was peddling snake-oil. I even had a go at it in one of the erratic Pistons posts that showed up around here a couple years ago, noting that after Ben Wallace left the Pistons' rebounding changed not one percent on either end of the floor. Ben Wallace got his rebounds from his teammates. (It turned out that Wallace's major skill was an ability to keep opponents off the free throw line.)

This did not take, unfortunately, and Berri has been permitted to say silly things about all sports that apparently intelligent people take seriously because he has "Princeton" next to his name. He moved on from basketball to "show" that NFL teams don't care how well their quarterbacks perform, only how high they're drafted…

Aggregate performance and draft position are statistically related. But as Rob and I argue, this is because in the NFL (like we see in the NBA) draft position is linked to playing time. And this link is independent of performance.

…that NHL goalies are indistinguishable from each other…

... there simply is little difference in the performance of most NHL goalies.

…and has returned to state basketball coaches don't understand who their best players are:

"... the allocation of minutes suggests the age profile in basketball is not well understood by NBA coaches."

Berri's at least had the common sense to stay away from baseball, where a horde of men with razor-sharp protractors wait for him to make a false move. (We will see later that collaborator JC Bradbury has not.) The statistical communities in football, basketball, and hockey are considerably more unsure of what the hell is going on in their chosen sport and are thus vulnerable to suggestion from an economist, even if it's one who seems to have never watched a sport of any variety.

The problem with all of Berri's outlandish theories is that they are wrong. Not because of old guys who peer into the soul of Andre Ethier and see a ballplayer, but because of other, more careful numbers from people who are looking for things that are true instead of things that are impressive to Malcolm Gladwell.

Quarterbacks

Berri's study actually shows that amongst quarterbacks who play a lot, draft position is not a strong factor in their performance. This is his magnificent leap:

For us to study the link between draft position and performance, we can only consider players who actually performed. It’s possible that those quarterbacks who never performed were really bad quarterbacks. But since they never played, we don’t know that (and Pinker also doesn’t know this).

Low draft picks who don't play only find the bench because of bias. A coach's decision to start one player over the other is a worthless signal. Coaches are dumb.

In reality, backup quarterbacks perform measurably worse than starters, and many different metrics show a strong correlation between draft position and performance.

Goalies

When you restrict your regressions to the top 20 goalies in terms of minutes, about half of the variation in save percentage appears repeatable. A standard deviation of talent is worth around ten goals. These days, a unit of five skaters who finished +50 at the end of the season would be heroes on the league's best team. Berri's undisclosed approach to the data set apparently takes goalies with far fewer than starter's minutes. A quick correlation run by Phil Birnbaum shows radically different r-squared values than those Berri finds just by upping the sample size. Maybe Birnbaum's numbers aren't dead-on—he doesn't use even strength save percentage, for instance—but he's not the one claiming a massive inefficiency. He's just showing that throwing a small r-squared out doesn't actually mean anything:

I don't know how the authors got .06 when my analysis shows .14 ... maybe their cutoff was lower than 1,000 minutes. Maybe there's some selection bias in my sample of top goalies only. Maybe my four seasons just happened to be not quite representative. Regardless, the fact that the r-squared varies so much with your selection criterion shows that you can't take it at face value without doing a bit of work to interpret it.

Age in the NBA

In the NBA, 23 and 24 year old players net more minutes than any other age bracket, and while the average age of an NBA minute is 26.6 this year there's a blindingly obvious explanation for this:

Berri and Schmidt think that NBA minutes peak later than 24 because coaches don't understand how players age. It seems obvious that there's a more plausible explanation -- that it's because players like Shaquille O'Neal are able to play NBA basketball at age 37, but not at age 9.

In sum: wrong, wrong, wrong, and wrong.

So what's going on here?

When you've got a hammer, everything looks like a nail. Berri's hammer is regression analysis, and he goes about hitting everything he can find with it until he finds something that seems vaguely nail-like from a certain angle. Then he proclaims a group of extremely well-paid subject matter experts dumb. When challenged about this, he says things like "regressions are nice, but not always understood by everyone." He calls the protestors dumb.

This is more than a logical fallacy: it's a worldview. In a post on a cricket study by another set of authors, Birnbaum points out the assumption built into a lot of economics studies. It, like most of Berri's work, runs a regression on some data and reports back that something fails to be statistically significant:

The authors chose the null hypothesis that the managers' adjustment of HFA [home field advantage] is zero. They then fail to reject the hypothesis.

But, what if they chose a contradictory null hypothesis -- that managers' HFA *irrationality* was zero? That is, what if the null hypothesis was that managers fully understood what HFA meant and adjusted their expectations accordingly? The authors would have included a "managers are dumb" dummy variable. The equations would have still come up with 4% for a road player and 10% for a home player -- and it would turn out that the significance of the "managers are dumb" variable would not be significant. Two different and contradictory null hypotheses, both which would be rejected by the data. The authors chose to test one, but not the other.

Basically, the test the authors chose is not powerful enough to distinguish the two hypotheses (manager dumb, manager not dumb) with statistical significance.

But if you look at the actual equation, which shows that home players are twice as likely to be dropped than road players for equal levels of underperformance -- it certainly looks like "not dumb" is a lot more likely than "dumb".

The goalie example is the most illuminating here: by adjusting the parameters of your study you can arrive at radically different conclusions. I'm not sure if Berri is intentionally skewing his results to get shiny Moneyball answers, but given how dumb his justifications are for the NFL study that's the kinder interpretation. Running around saying that we don't know that the average sixth rounder isn't John Elway waiting to happen because they can't get on the field is obtuseness that almost has to be intentional. On the other hand, he does blithely state he's "not sure there is much to clarify" about his assertion that NFL general managers are on par with stock-picking monkeys when it comes to identifying quarterbacks, so he may be that genuinely clueless. (The Lions tried a stock-picking monkey. It didn't work out.)

There's often a kernel of truth in a Berri study. When the Oilers were casting about for a goalie, smart Oilers bloggers were noting the glut of basically average goalies available and jumped off a cliff when they signed a mediocre 36-year-old to a four year, $15 million dollar deal when they could have signed two guys for something around the league minimum and expected about the same performance. That's something close to the criticism Berri levels with the volume turned way down. Hockey and football and basketball are not baseball. It is incredibly difficult to encapsulate performance in any of these sports in statistics. So when Berri makes a proclamation that NHL goalies are basically the same based on plain old save percentage—which isn't even the best metric available—he ascribes more power to a stat than it deserves and simultaneously ignores a raging debate about one of the most difficult questions in sports statistics to get a handle on.

At the very least, the questions Berri attempts to tackle with really complicated regressions are murky things best delivered with a dose of humility. Instead Berri and colleagues say there is "simply" no difference, that his research is "not understood by everyone," that a formula that declares Jeff Francouer worth 12 million a year is justifiable and that protestors are making "consistent basic errors in logic, economics and statistics" when any minor league player making the minimum could replace his production, and that David Berri went to Princeton. If he bothers to respond to what's admittedly a pretty shrill criticism, he will undoubtedly state that if only I had managed to understand his papers the many ludicrous conclusions easily disproved by competing studies (QBs, save percentage), simple facts that blow up the idea being presented (NBA minutes), or common sense (Rodman, Francouer) would have come to me in an epiphany.

These things are all ridiculously complicated and it's obvious with every response to another Berri study that declares someone dumb that different views on the data produce different results. Berri's overarching thesis is that subject matter experts make huge errors because they refuse to look at data from all possible angles. Stuck in their ruts, they robotically bang out decisions like their forefathers. Statistician, heal thyself.

There may be some social utility in distracting economists from theorizing about the economy, but there's no utility in the domain they're actually tackling.

In 1806 Pfuel had been one of those responsible for the plan of campaign that ended

in Jena and Auerstadt, but he did not see the least proof of the fallibility of his theory

in the disasters of that war. On the contrary, the deviations made from his theory

were, in his opinion, the sole cause of the whole disaster, and with characteristically

gleeful sarcasm he would remark, `There, I said the whole affair would go to the

devil!’ Pfuel was one of those theoreticians who so love their theory that they lose

sight of the theory’s object—its practical application. His love of theory made him

hate everything practical, and he would not listen to it. He was even pleased by

failures, for failures resulting from deviations in practice from the theory only proved

to him the accuracy of his theory.

—Leo Tolstoy

Thanks for a nice share

Comments