Chart? Chart! Wisconsin Defending Ball Screens (Pt 2)

In Part 1, I covered some of how Wisconsin guarded Michigan’s staple ball screen action in the Wolverines’ loss to the Badgers a little over a week ago. Against the pick and roll, one of the most common plays in all of basketball, and against other ball screen looks, Wisconsin ran their customary coverage: the on-ball defender went over the screen while the big executed a “drop” — sinking into space, containing the ball-handler, cutting off passing lanes for a dish to the roller, and allowing the on-ball defender to recover to the ball. This coverage was often complemented by a “tag” from a defender who wasn’t directly involved in the play; Wisconsin often left (and usually recovered to) a shooter to impede the roller’s path to the basket.

Part 1 goes into more detail regarding how Michigan was able to attack that drop coverage in the pick and roll game (and it also includes a link to a detailed description of that defense). Essentially, there are a few reads the ball-handler has to make: whether to shoot, drive, dish or kick, depending on what kind of opportunities are there.

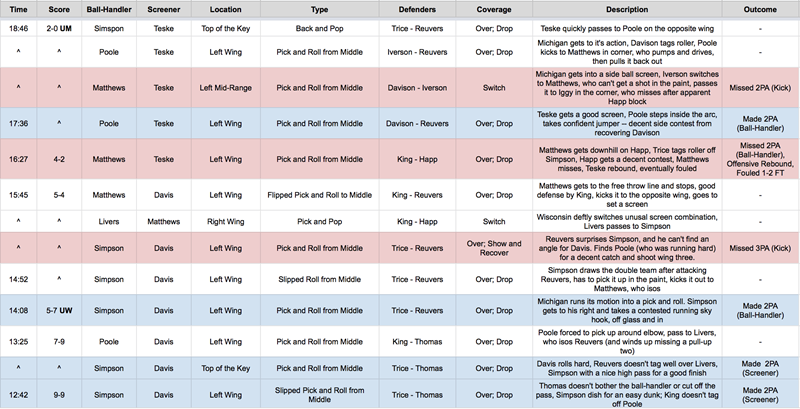

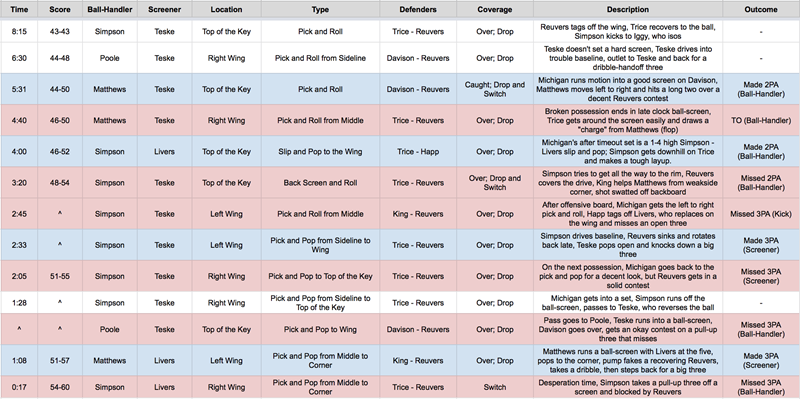

Pick and Roll

- 36 ball-screens

- 9-17 on twos

- 1-5 on threes

- 2-4 on free throws

- 4 turnovers

- 23 points on 28 possessions

Michigan can slice up plenty of teams with its pick and roll game (their hot start against Indiana was fueled by looks from that action), but Wisconsin’s top tier defense was excellent in this game, holding Michigan to a season-low 0.82 points per possession. 42% of Wolverine possessions in this game ended with a pick and roll — at 0.82 PPP. Michigan has three players consistently operating the ball screen: Zavier Simpson, Charles Matthews, and Jordan Poole. They make for an interesting mix of strengths and weaknesses, and between the three of them, Michigan has one of the best ball screen offenses in college basketball.

Wisconsin defended the pick and roll well for a couple of reasons: they executed the drop coverage well on most screens regardless of personnel, and Nate Reuvers was solid as the key piece of their defensive scheme.

On this play, Reuvers drops on a Simpson - Teske pick and roll — maybe Michigan’s best ball screen look — and Wisconsin clogs the paint. Brevin Pritzl tags off Ignas Brazdeikis, and Iggy attacks the closeout (something he does really well), but commits a charge (it was that kind of day for him). The Badgers wanted to take away Simpson and Teske, though, and Simpson has to make a difficult pass to kick it successfully to a shooter. Khalil Iverson goes over the screen and recovers; Reuvers contains both Simpson and Teske by dropping into the paint; Pritzl tags well to prevent a pass to Teske and has to make a tough close out. Wisconsin got a stop. This was a fairly standard outcome.

The Badgers were really sound (they ran the drop coverage on 73% of Michigan’s ball screens, and switched appropriately against more unusual Michigan ball screens) and might have the best pick and roll defense that Michigan will see all season. They’re in the top ten in adjusted defensive efficiency according to Kenpom / Torvik. Because of the Wolverines’ outstanding defense, the game was close late, but the Badgers shut down their pick and roll game — and Michigan shot 5-18 on threes. Sometimes the Wisconsin defense dictated a good look from three, and Michigan shot 28% on threes. And thus, Michigan suffered its only loss of the season.

But even though Wisconsin held Michigan’s pick and roll in check, the Wolverines had a different look too: the pick and pop.

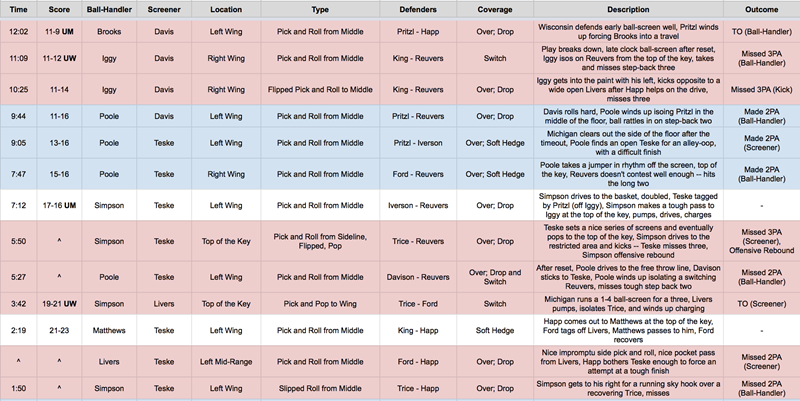

Pick and Pop

- 16 ball screens

- 1-2 on twos

- 4-9 on threes

- 1 turnover

- 14 points on 12 possessions

During most Michigan games, the broadcast team references John Beilein imploring Jon Teske to shoot the three whenever he lets one fly. The Big Sleep was 3-15 from behind the arc over 13 games before Big Ten play resumed, and he’s shot 9-20. Teske was comfortable as a shooting threat in practice, but only attempted one all of last season as Moe Wagner’s backup. Beilein has run a five-out system for many years — Pittsnogle! — and having a center who can shoot unlocks a lot of possibilities for the Michigan offense.

Teske is renowned for his defense, and he’s emerged as a valuable offensive player. 77% of his made shots this season have been assisted, but he can create good shots with his ability to read the defense and find space to operate. Last season, Teske would sometimes settle into the mid-range for a catch-and-shoot jumper after setting a screen. He’s expanded his range this winter and can stress the defense even more.

This was a big three by Teske. Simpson and Teske get into a side ball screen with that side of the floor cleared out, and Reuvers sinks to contain the baseline Simpson drive. Brad Davison is too far away to rotate over to Teske, and Reuvers is too far to recover and contest the three. Instead of rolling to the rim or trying to find space in the elbow area, Teske is comfortable enough to stay where he is, spot up, and knock down the open shot. On the next possession, Michigan ran another pick and pop for a Teske three to tie; Reuvers reacted quickly enough to get in a good contest to help force a miss.

[More on the pick and pop after the JUMP]

Pick and Pop with Teske

- 11 ball screens

- 0-1 on twos

- 3-7 on threes

- 9 points on 8 possessions

- Teske was 2-4 shooting threes from pick and pops

Michigan ran progressively more pick and pop action over the course of this game (eventually popping on their last five ball screen possessions). In Part 1, I took screenshots of the first ball screen possession of the game for Michigan: Reuvers dropped, Davison tagged the roller, and the paint was clogged for the pick and roll. The Wolverines didn’t run a pick and pop until just under six minutes left in the first half, and this is what it looked like:

Teske feigns setting a screen from Simpson’s right.

He flips the pick so the screen is coming from the middle of the floor. Reuvers starts to sink; D’Mitrik Trice goes over the screen.

Simpson starts driving downhill, chased by Trice. Reuvers is containing the drive, but Teske is still where he set the screen.

Teske relocates along the arc for a better passing angle, while Simpson is effectively double-teamed in the middle. He knows Teske is open, and makes a good pass.

Here’s the play at full speed:

Teske doesn’t make the shot, but it’s a great look against the Wisconsin defense. Simpson’s driving with his left, so he’s not much of a threat to score (relatively speaking), but Wisconsin’s ball screen coverage dictates that Reuvers must stay with him until Trice can recover. That this is a vertical pick and pop — with the pass coming from the paint to the top of the key — opens up more space than Michigan’s slip and pop action. It’s also a subtle maneuver by Teske to create the shot: he flips a screen, settles at the three-point line, and then makes himself available for a shot. He missed, but it’s a great look.

Simpson and Teske have great chemistry, and much of Teske’s production is derived from ball screens — many of which are assisted by Simpson. As a freshman reserve who barely played, Teske looked lost offensively. He’s now able to function in a complex role as the fulcrum of Michigan’s offense, making sequences of reads quickly. As he’s settling into the second half of his junior season, Teske’s willing to shoot the three, and that opens up plenty of possibilities for the Wolverines. Against ball screen coverages like Wisconsin’s, the pick and pop game can be deadly. Against the switching defenses that Michigan’s seen more of in recent seasons, it usually isn’t.

When Isaiah Livers is in the game at the five, or even at the four, Michigan likes to have him slip the screen and spot up from the opposite wing or the top of the key (they also like running that action with Iggy, and actually ran it with Iggy as the ball-handler and Poole as the screener on the final possession against Minnesota). Against Wisconsin, Austin Davis handled most of the minutes as the backup five, so Livers set relatively few ball screens — just four. All four were charted as pick and pops.

Watch Ethan Happ on this play. Michigan starts in a 1-4 low alignment and slips a pick and pop with Livers. Trice does well to stay with Simpson and challenge the shot, but Happ’s taken out of the play by the threat of Livers shooting from the top of the key. He can’t execute the drop coverage without leaving Livers wide open, Reuvers doesn’t leave Teske beneath the basket to help (even if he did, Simpson could dish to Teske for an easy bucket), and Simpson scores over Trice. Michigan ran this out of a timeout, something they’ve done a couple times lately.

Livers is an interesting option as the backup five, but like Davis, Michigan’s offense can become a little more one-dimensional when he’s on the floor in that capacity. With Davis, Michigan runs pick and rolls constantly, sometimes scrapping their motion entirely to run spread ball screens. With Livers, Michigan runs frequent pick and pops (though against Indiana there were some plays where Livers was able to get to the rim — he just didn’t finish). Not only is Teske the best defensive big, he’s capable of presenting the defense with a variety of looks after setting a ball screen and reading the defense.

In the rematch against Wisconsin, I’d expect Michigan to go to the pick and pop action early to put Reuvers in tough situations. While it’s unlikely that the Badgers will be as successful in shutting down Michigan’s ball screen offense, the Wolverines might need to coax Reuvers — or whoever is guarding the screener — away from the paint.

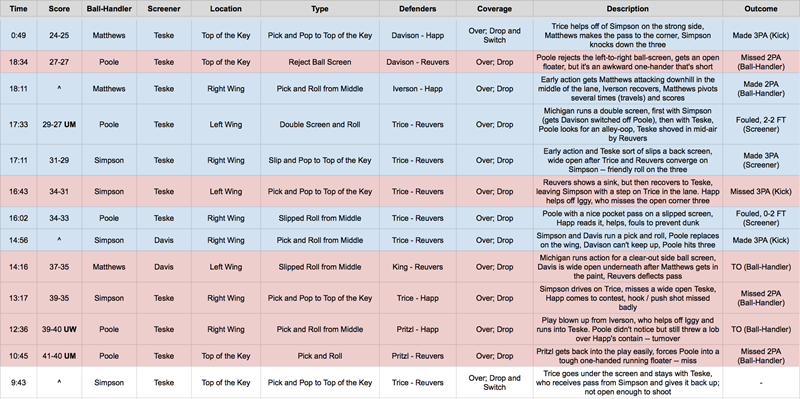

I compiled these numbers before the contours of this post took place, so here they are, even though I didn't really focus on how Michigan looked with different ball-handlers:

Zavier Simpson

- 23 ball screens

- 4-7 on twos

- 3-9 on threes

- 1 turnover

- 17 points on 17 possessions

Jordan Poole

- 14 ball screens

- 4-7 on twos

- 0-1 on threes

- 2-4 on free throws

- 1 turnover

- 10 points on 11 possessions

Charles Matthews

- 10 ball screens

- 2-4 on twos

- 2-2 on threes

- 2 turnovers

- 10 points on 8 possessions

They were all pretty much the same!

Here's the chart again:

January 30th, 2019 at 1:03 PM ^

So, pick and pops worked ok.

It'd be nice if Livers could develop roll-man skills. Seems like a good bet for next year; it would be a powerful option if it shows up this year.

Iggy would be a great one to run this action if he ever passed, but he doesn't.

January 30th, 2019 at 1:44 PM ^

I'm having trouble getting acquainted with all of this since my school has only recently transitioned to basketball from football as the primary focus of athletic interest. I have enjoyed this transition because I really enjoy watching Beilein teams. Especially when they win. I even paid for the annual KenPom subscription. I've watched almost every game this year, all of them since Villanova.

But the first Ball Screen article lost me at "Ball Screen". I'm not sure how a Ball Screen differs from a Flat Screen or a Ball Point. Looking through the pictures in either article, all I see is men running around playing basketball.

If anybody needs me, I'll be reading Basketball for Dummies on my vacation next week. At some point, maybe I'll be able to come back to these excellent analyses and understand them a little.

Comments