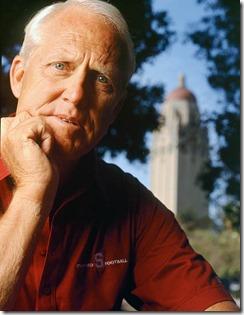

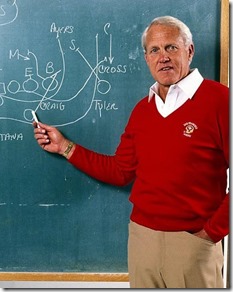

bill walsh

It can happen.

Some NFL beat writers have been going to great lengths lately to poo-poo the idea of a successful NFL coach going back to college. Well, as you can imagine there are a bunch of NFL guys who've gone back to coach college, though not so many with a legit shot at an NFL position in a short (year-ish) window.

Typically when it happened, it was successful college coach who wasn't very successful in a short NFL stint. There's Saban and Spurrier of course. Also new Nebraska head coach Mike Riley spent three bad years coaching the Chargers in between tenures at Oregon State. Dan Devine, Bill Callahahan, John Mackovic, Butch Davis, Rich Brooks, Gene Stallings, June Jones, Paul Wiggin, Lane Kiffin (giggle), Howard Schnellenberger, Bobby Petrino, Bill Arnsparger, and Lou Holtz all coached one to four years in the NFL without getting to the playoffs. Dan Henning, Forrest Gregg, and Dennis Erickson are three examples of established pro dudes who exhausted their NFL opportunities before accepting demotional collegiate positions.

Between 8 and 10 of the 30 NFL head coaches I could find who went back to college appeared to have some competing pro prospects. They were:

|

| Though just 60 when the took the job, Walsh, who'd walked away on top of the NFL at 56, wasn't expected to be a long-term answer for Stanford. [Gerry Gropp] |

Bill Walsh

NFL Record: 92-51-1 with 49ers, 1979-'88. Won Superbowls, established a dynasty, staffed a generation of NFL jobs with his assistants. All-around badass.

College Record after NFL: 17-17-1 at Stanford, 1992-'94

Walsh is the go-to comparison because he's certainly the greatest NFL coach to ever return to the college ranks, but he's also not very instructive, since he walked away from coaching for three years before surprisingly returning to college.

After winning Super Bowl 23 Walsh voluntarily retired, citing burnout, and went to work in broadcasting. Everyone expected he would continue to do so. But in 1992 Stanford, where he'd developed the West Coast offense and been head coach for two years in the late '70s, begged him to come back (he turned 61 that season). There's a book about the return, wherein Walsh says he didn't like broadcasting and was getting an itch.

Certainly ANY NFL team would have taken him. And the Stanford he returned to wasn't a Michigan, but they had gone 8-4 in '91 and returned most of that team. In his first year back, Stanford was 10-3 and shared a piece of the conference championship (but didn't get the Rose Bowl nod, having been creamed by Washington). They regressed back to near the bottom of the conference in 1993 and 1994, losing a lot of close games to top 10 teams in that period, and Walsh re-retired. He lived out his days around the Stanford program, teaching classes and writing books.

[Jump for guys who aren't in the conversation as greatest coach in history]

left: Bryan Fuller

Earlier this offseason I stumbled onto an old article where Bill Walsh wrote what qualities he looks for when drafting various positions. Meant to be a one-off on the offense, I took requests for a defensive version and broke it up into D-Line, linebackers, and now, finally, the defensive backs. The idea is since the coaching staff is building a "pro-style" team with principles more akin to the Walsh ideal that dominates the pros than the collegiate evaluations made on scouting sites and the like, we shall re-scout the 2013 roster for Walsh-approved attributes.

Since coverages have changed the most since Walsh's day—a reaction to the spread—this is probably the least valuable of the series. To bring it back on point, I've gone off the page a little bit to note some of the attributes that NFL defensive coaches are looking for nowadays, and what those changes mean.

Strong Safety

Plankamalu / Shazorvacs/ M-Rob if all quarterbacks were Brian Cleary

Walsh Says: 6'3/215. Now hold your horses before going all "SHAZOR?!?" on me—I'm making a point: The type of player you have at safety depends on the type of system you want to run and the type of player you have everywhere else. If you're going to be playing more odd coverages (cover 1, cover 3) then you want your strong safety to be more of a run support guy, in many ways a fourth linebacker. If your base coverage is even (cover 2, cover 4) the strong and weak safeties will be more similar:

"There are other systems of defense where both safeties play a two-deep coverage and only occasionally come out of the middle to support the run. They basically play the ball in the air, the middle of the field and the sidelines. When you do that, then the stress is on the cornerback to be the support man.

So you must keep in mind these various philosophies when considering what types of cornerbacks and safeties you want to put together in forming a defensive secondary."

The attributes of your defensive backs should be complementary. Here's what Walsh is getting at: your backfield has to be able to defend the pass first and the run second. And here's the key: the more you can trust one player to handle coverage without help,  the more you can stock up on extra run defense with the other guys. If your backfield already has plenty of coverage, you can have a strong man:

the more you can stock up on extra run defense with the other guys. If your backfield already has plenty of coverage, you can have a strong man:

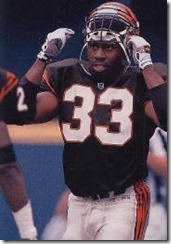

"The strong safety is historically the support man. He must have some of the traits you look for in a linebacker. In fact there have been some hybrid players in that position. Cincinnati had David Fulcher [right], who was as big as some linebackers but could function also as a safety. The Bengals moved him weak and strong, inside and outside and he became that extra man that the offensive run game had to account for but often could not block.

…

"But the typical strong safety is someone who can hit and stop people and respond spontaneously and go to the ball. Naturally, the more coverage talent the man has the more you can line him up on anybody."

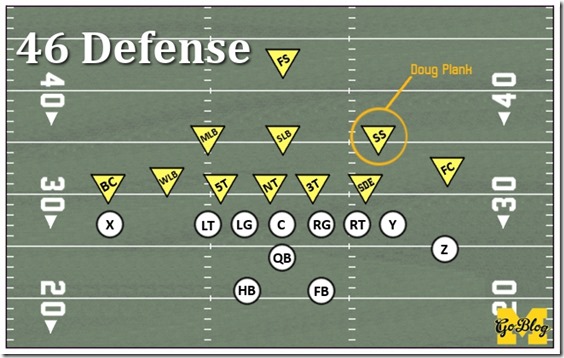

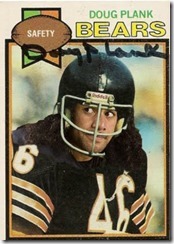

Today, defensive coordinators sit on porches, remember when you could play a guy like Fulcher, and say "those were the days." The epitome of this type of safety is former Buckeye Doug Plank, who defined his position to such a degree that the defensive system itself was named for his number (46).

It's also called the "Bear" defense because it was the Bears

This defense was at the height of its popularity when Walsh joined the 49ers in 1979, and it was this defense his model passing concepts shredded. The defense played to Plank's strengths as an overly aggressive, hard-hitting run stopper with some coverage skills. The SAM linebacker in today's anti-spread sets (e.g. the 3-3-5's "Spur") is a closer analogue to the Plank-style player than the modern strong safety, with the key difference being that, as a safety, you couldn't put a blocker on a 46 without removing one from a lineman or linebacker, meaning the SS could flow cleanly to the point of attack and wrack up ridiculous tackle numbers.

College teams loved this, since passing quarterbacks were hard to come by and the big boys were running three yards and a cloud of dust (and later the option). A lot of cool names for linebacker-safeties were passed down from this period, such as the "Wolf" on Bo's teams, or the "Star" (names which today are coming out of retirement for the nickel-SAM hybrid position in base 4-2-5 anti-spread defenses).

Walsh's Favorite Wolverine: Why does a mid-'70s response to off-tackle NFL running games matter to a collegiate defense in 2013? Well because we have a really good free safety, and play tight end-heavy outfits this year in UConn (T.J. Weist, a rare member of the Gary Moeller coaching tree, is taking over there), Penn State, Michigan State, and Iowa, with the outside possibility of a Wisconsin if we make it to the conference championship. Also because the coaches have been subtly putting safety-like objects (Woolfolk, Gordon, and now Dymonte Thomas) at nickel, and recruiting a few linebacker-sized safeties.

I don't know what he'd think of Kovacs. We loved him, but Jordan had two weaknesses: 1) his lack of overall athleticism made exploitable if left in wide coverage (see: his abusing by Ace Sanders on the last play of the Outback Bowl, and the utter disaster that was GERG's attempt to play Kovacs as the free safety in 2009), and 2) his lack of size made him blockable if a lead blocker could get to him (see: bad things happening whenever Mouton abandoned contain).

I don't know what he'd think of Kovacs. We loved him, but Jordan had two weaknesses: 1) his lack of overall athleticism made exploitable if left in wide coverage (see: his abusing by Ace Sanders on the last play of the Outback Bowl, and the utter disaster that was GERG's attempt to play Kovacs as the free safety in 2009), and 2) his lack of size made him blockable if a lead blocker could get to him (see: bad things happening whenever Mouton abandoned contain).

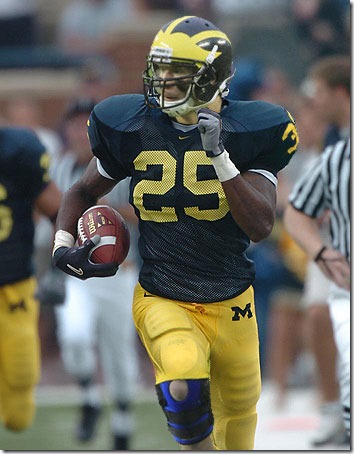

He would have loved Ernest Shazor, a knife blade listed at 6'4/226 with a scatback's acceleration who loved nothing better than demonstrating the force equation. Brian calls Shazor "the most overrated Michigan player of the decade" because he has to live with the bolded subconscious of UFR, and nothing pisses off a figment of a blogger's imagination like a safety who gives up a big play in coverage.

Here's the point: the ideal safety would be a dude with the size and stopping power to pop a lead blocker and make the tackle or lay out a guy like Shazor, read and react like Kovacs, and cover like Charles Woodson. That human doesn't exist. A combo of epic athleticism with plus headiness and serviceable tackling and size equals Ed Reed or Sean Taylor. Epic headiness with plus size and serviceable everything else nets you Doug Plank, with plus athleticism: Ronnie Lott, Troy Polamalu or Rodney Harrison. The trick is to have epic everything between your safeties; for strongside then it's not Ernest Shazor or Jordan Kovacs; it's SHAZORVACS!

What to look for in a Scouting Report: At either safety position, instincts rate highly and speed after that (less so for the strongside). You're looking to first make sure you have enough coverage in the entire backfield, and once you do you can use this position to stock up on linebacker traits: tackling, size, taking on blockers, personal contribution to local seismic activity, that sort of stuff.

What you can learn on film: Everyone loves those bone-jarring hits and coaches are more than happy to put them in a recruiting video, but not all hits are created equal. Sometimes they're generated by another defender cutting off the lead blocker, other times it's your guy reading the play so early he can go all-out on the hit. More important is what happens to the ballcarrier: he needs to go down. Safeties are going to be left in space, and making that tackle is more important than making the offensive player wish he'd never met this oblong brown thing.

What could signal bust potential: Remember you want a safety, not a horse, i.e. overrating the secondary, linebacker-y attributes and expecting the rest to come along. Adequate coverage and good instincts need to be there or else this guy is just a platoon player. "May be a linebacker on the next level" is a red flag, unless he actually becomes a linebacker. Brandon Smith's recruiting profile is instructive.

It's usually good policy to discount ESPN's opinion when it's in wild disagreement with the other services, but here I tend to give their rip job ($, "he's not a fast-twitch athlete and lacks explosive quickness and speed"; "Takes too long to reach top speed"; "He can be late, takes false steps and doesn't see things happen quickly enough") some credence. Reasons:

- Rivals started off very high on him, ranking him around #50, but steadily dropped him as the year progressed despite his status as a high-profile uncommitted player.

- Despite all the guru accolades Michigan's main competitors were Rutgers and South Carolina; other offers came from Maryland, NC State, Wisconsin and West Virginia. He wanted offers from Florida and Ohio State which never came.

- You always risk looking like a tool when you rely on your super awesome scouting skills and six plays on youtube to discern a kid's fate, but... yeah, I didn't think he was all that.

The guy left in a huff after they tried to wring the last bit of value out of him as a Doug Plank-like extra linebacker vs. Wisconsin, and Wisconsin ground us to dust, but then Smith was a high school quarterback whose development as a defender had to come almost entirely from the Rodriguez-era coaching staff. Anyway you've seen this again and again: rave reviews for the guy's "frame" and a profundity of attributes that would make him seem a really nice horse, combined with not nearly enough "makes plays." First have all of the safety stuff: can read and react, cover, and tackle in space. Then care about the size.

How our guys compare: Jarrod Wilson (6'2/196) remains my favorite to start at this spot because he is adequate (not yet plus) in coverage and the other guys aren't. Like the Jamar Adams he reminds me of, Wilson doesn't stand out in any category but doesn't have any major holes in his game other than being young.

The other leading candidate is Marvin Robinson who scares the hell out of me. He was a big-time recruit early in the process thanks to apparently having an early growth spurt, and his profile was filled with horsey metaphors. The same player still hangs on that frame (he arrived at 203 and never deviated more than 3 lbs from that) and hopes for him hang on the comparative competence in coaching plus the fact that being behind Jordan Kovacs is a perfectly reasonable excuse for not seeing the field earlier.

The redshirt freshmen at this position are stiff and linebacker-ish with instincts, more Plank than Polamalu. Jeremy Clark is all of 6'4/201 and did an okay job against the run in the Spring Game I covered in this space a few weeks ago, but lacks speed. Allen Gant also had instincts praised as a recruit, but also lacks the kind of athleticism and would at best develop into a slightly bigger and less heady Kovacs. If going forward Michigan can develop a superstar at the other safety spot or with a corner, they might be able to Plank it with one of these guys—when Woodson gave us that opportunity in '97, Daydrion Taylor and Tommy Hendricks went ham.

Thomas Gordon is super-instinctive and would be a perfect fit here except he's needed at the more important free position he's been playing.

[The rest, after the leap.]

Sinestral: Ross, Ryan and Clark|Bryan Fuller, MGoBlog. Dextral: Bill Walsh

First, a Chag Sameach to my fellow tribesmen and a Happy Turtleversary to the wingnuts.

We now continue with the Bill Walshian rundown of the 2013 roster. Since Michigan's offense and defense schemes are kindred spirits of the great 49er teams of the '80s, I've found it somewhat useful to re-scout Michigan's players on the same factors that the legendary coach used to evaluate his draft picks. How do we know what Walsh drafted on? Well wouldn'tchya know it, he provided it in a 1997 article for Pro Sports Exchange that Chris Brown (Smart Football) discovered.

Part the first was the entire offense. Part the second was the interior D-Line. Now we're on to the linebackers, among whom I include the WDEs.

Weakside End

Bruce Smith/ James Hall / Frank Clark by Upchurch

Walsh Says: 6'5/270 or 6'3/245 depending on type. It's complicated so I'm going to spend some extra time here. His DE descriptions bounced between what you want from 3-4 DEs, which is the 3- and 5-tech in Michigan's defense, and pure pass rushers. Ultimately Michigan's WDE is closer to the pass-rush-specialist-who-stops-runs-too job description of a Walshian 3-4 weakside linebacker than a blocker-sucking interior DL, so they go here with the LBs. Speed and quickness are now very much in play:

Must have explosive movement and the ability to cover ground quickly in three to five yards of space. The ability to get your shoulder past the shoulder of the tackle. This makes for a pass rusher. With that there is quickness because it sets up a lot of other things.

From the outside linebackers description we get this:

These pass rushing outside linebackers must have natural gifts, or instincts for dealing with offensive tackles who are up to 100 pounds heavier. Quickness is only part of it. They must know how to use leverage, how to get underneath the larger man's pads and work back toward the quarterback. And he must be strong enough to bounce off blocks and still make the play.

The rush DE needs to have some finesse. This site never misses an opportunity to knock on Will Gholston so I'll do that: Gholston has more than enough explosion and strength, and is an excellent tackler but the big hole in his game is he doesn't get leverage or bounce off blocks. This is why State deployed him mostly SDE this year while Marcus Rush was the premier pass rusher. Walsh says it's all the same if you can push a tackle as go around him, but being an okay jack of all trades here isn't as valuable as being super disruptive at one or the other.

Overall strength is important. You don't have to be a Mike Martin beastmonster in the weight room but a WDE has to be strong enough to not get turned by the tackle. This is also a technique issue though it's not a skill that needs years to develop—a big sophomore year leap is expected at this position as the kid gains weight, strength, and the footwork and balance to be able to keep his shoulders pointed toward the football.

As echoed in Mattison's statements in 2011 regarding WDEs, Walsh calls his rush DEs "the substance off the defensive team" since their ability to put pressure on the quarterback can make or break a defense. This is why great DEs are at such a premium in today's NFL.

The last piece is willpower, which in scouting parlance becomes "high motor." WDEs typically get rotated a lot because they burn a gazillion calories on each play. Because this spot is supposed to win 1-on-1 battles and kill plays himself, success on the second and third moves can make a huge difference.

Walsh's Favorite Wolverine: If James Hall and Larry Stevens had a baby, and that baby came out 6'5/260 and immediately ate the doctor. Michigan just hasn't had the freaks here unless you count Woodley and I'm saving him. Stevens didn't have the sacks but generated hurries. And Hall: because he's 6'2 every scout from the early recruiting years to modern NFL trade talkers underrates him, despite consistent production at every level. Hall is second (to Graham) in career sacks and 6th in TFLs among Wolverines and was the 1997 team's secret weapon. Both guys were often extolled for their virtues under the hood.

What to look for in a Scouting Report: EXPLOSIONS! I know I said this for SDE but even more so. You know these guys on sight because the innate quickness and strength makes them terrors against high schoolers. Skipping over the blue chips (or like Ra'Shede Hageman who would have been a blue chip if he accepted Florida's offer to play DE rather than Minnesota's offer of tight end) 3-stars who shine seem to have athletic tickmarks or the proverbial motor. I noticed some of the big performers from high school All-American games (Ray Drew, Alex Okafor, a million dudes who went to Florida) tend to fare well—about the worst among Army game standouts of yore was Victor Abiamiri, who was still pretty good. The pushers had ridiculous squats (Simon's was 700!)

What you can learn on film: How fast he gets into the backfield, adjusted for competition. You're looking for that quick burst. The great ones just look completely unblockable—like the guy blocking him doesn't seem to have any leverage.

What could signal bust potential: Size. Rivals tends to put its favorite DEs at "SDE" for this reason. If you browse through the five-stars you generally find two categories: high-effort guys who were early contributors and are or are on track to be NFL draft picks at defensive end, and Pierre Woods/Shawn Crable-like linebackers whose recruiting profiles said they would grow into Jevon Kearse. There's a reason they called Kearse "the freak."

How our guys compare: Frank Clark and Brennan Beyer are the two sides of the WDE coin. This refrain from MGoBlog is becoming tiresome but Beyer seems the stronger and more responsible one and Clark is the greater X-factor. We overplay this; both would still fall more into the finesse side than, say, John Simon, and both seem to top out as useful but not stars.

Ojemudia is kind of a James Hall but more akin to Shantee Orr. Where James Hall was small but had the size to stand up to a good shove when needed, here you have a dude with explosiveness and great hands for pass rushing but is going to be dead meat if doubled and run at, and is therefore best deployed as a 3rd down or [blank]-and-long specialist.

Early enrollee Vidauntae "Taco" Charlton, who's already 6'6/265 on Michigan's spring roster, is the closest thing to Walshian dreams. On film though a lot of times you just see him blowing something up because they didn't block him, and though this probably had a lot to do with being way bigger than high school tackles in Central Ohio he didn't play with much leverage after the snap. The reason for all the Tacoptimism is he blew up the camp circuit. He probably still needs a year to work on technique since he spent most of high school in a 2-point stance. Warning: he doesn't check the motor box.

[Linebackers, after a leap.]

71