2015-16 basketball review

Upchurch / Upchurch / Sherman

Previously: Zak Irvin, Muhammad-Ali Abdur-Rahkman, Duncan Robinson, Mark Donnal

With the news that Kam Chatman is transferring, what was a five-man rising junior class is now just two. Four players (including Spike – who will be playing for Purdue next season) who played last season are leaving with remaining eligibility. Ordinarily, this would be cause for considerable depth concerns, but since Michigan returns all five starters from last season’s tournament team – something that very few teams can say in this day and age – experience is actually an advantage for this team moving forward. Very rarely are teams able to sustain five-man lineups year over year and it’s reasonable to expect that Walton / Rahkman / Robinson / Irvin / Donnal will execute crisp offense together on the floor. If improvement from Wagner vaults him past Donnal (who’s much more of a known quantity) on the depth chart, all the better.

Right now, that depth chart might look like this:

We’ve seen the effect that limited depth can have on players, and it might be a concern again. Walton will have a very capable backup in Xavier Simpson, and fellow freshman Ibi Watson will get a shot behind MAAR, so the guard situation is much better than it was a year ago. There are enough big men: Donnal and Wagner will run into foul trouble, so there’s a need for a third option to emerge, but all in all, there are enough bodies at the five.

The main concern comes on the wing – and that’s why the departures of Dawkins and Chatman might be felt the most. Michigan has two open scholarships for next season and desperately could use a wing with immediate eligibility (either as ideally a grad transfer or a 2016 recruit) to offset those losses: Dawkins was Michigan’s sixth man and played just under 40% of available minutes, while Chatman chipped in 12%. By the postseason, both were essentially used only to rest the starters – Robinson and Irvin each played right around 90% of available minutes in the Wolverines’ five postseason games. As it stands, those two are the only wings left with any experience.

None of the departures – Aubrey Dawkins, Ricky Doyle, and Kam Chatman – are particularly unexpected; Dawkins fell behind Duncan Robinson and saw his dad take a mid-major coaching job; Doyle and Chatman were on the periphery of the rotation and a path to significant minutes for either was hard to find. Still, all three were good enough to play last year, and their minutes will need to be replaced. Doyle’s minutes will be split easily between Donnal, Wagner, and the freshmen bigs; Robinson and Irvin probably can’t handle many more minutes, let alone taking all the minutes vacated by Dawkins and Chatman.

[What will Michigan be losing? Find out after the JUMP]

Sherman / Dressler / Upchurch

Previously: Zak Irvin

After last season, I wrote this in MAAR’s recap:

(I know Abdur-Rahkman is from Allentown, which is a little more than an hour from Philadelphia.)

While not the basketball Mecca that New York used to be or Chicago and LA are now, Philadelphia has still contributed immensely to hoops culture, producing greats like Wilt Chamberlain and Kobe Bryant, and – more relevant to college hoops – the series of rivalries between the “Big Five” of Villanova, Temple, St. Joe’s, La Salle, and Penn. Among other smaller Philly hoops stories, there’s the idea of the “Philly Guard” archetype.

As far as I can tell, the construct of a “Philly Guard” exists somewhere in the intersection of Allen Iverson and Rocky, an attacking combo guard bestowed with toughness and competitiveness platitudes. Though Abdur-Rahkman is 6’4, his high school film (and flashes of his play at Michigan) suggest that he could very well be a traditional Philly guard… despite not actually being from there. Only 20% of his two-point field goals at Michigan were assisted, he can play the one or the two (though Beilein’s system makes little distinction between the two), and he often injected life into a lost season with occasional bursts of physical ability – my favorite was when he pretty much made Jake Layman run and hide instead of contesting a dunk attempt.

Rahk is one of my favorite players on the team, mostly due to his uniqueness – there’s something about his game that can’t be replicated by anyone else. Since we’ve only seen half a season of him, it might be a while before I can pin down that essential quality about him, but I’m firmly on the bandwagon. Maybe this label will fit him in time, maybe not.

It’s clear what that quality is: more than anyone else on the roster, MAAR can create his own shot and get buckets. Before the season, he was the fourth guard on the depth chart, but by the end, he’d become the best member of the five-man 2014 class and ranked third in team MVP voting. Moving forward, it’s clear that Rahk has locked down the two-guard spot, and – as someone who’s mature for his class – he projects to be at least a solid starter as an upperclassman in the next two seasons.

Often, Michigan’s offense had to work hard for quality looks – instead of seeming effortlessly devastating, the Beilein offense more frequently was run through the ringer, using every constraint and trick to get the smallest windows of opportunity. While they were the most capable creators on the team, going through Derrick Walton or Zak Irvin usually came difficultly, especially against quality defenses. Very rarely were either able to take defenders one-on-one for a bucket, and even though both are above average passers, neither were quite explosive or agile enough to get open at the rate to routinely set up others (in contrast to Caris LeVert, for example). While both are good out of the pick-and-roll, neither are able to attack aggressively in those sets on a consistent basis.

Enter Abdur-Rahkman, a guy who wasn’t able to sustain a high-level usage rate, but someone who was able to do some of the things that Walton and Irvin couldn’t.

[After the JUMP, more on MAAR]

[This is a series reviewing last year's primary contributors]

via Ace

It’s worth remembering that Zak Irvin entered the season at less than 100% after losing months of practice and workout time to a back injury. He struggled to return to form early in the season, shooting an abysmal percentage from three – no doubt due at least partially to the lingering effects of the injury. Then, just like last year, he was thrust into a prominent offensive role due to injury and had to stay on the court for nearly entire games in conference play (only Yogi Ferrell played more minutes in B1G games in each of the last two years). After LeVert’s injury, Irvin was forced into much tougher shots, much more offensive responsibility, and a critical leadership role with both seniors injured.

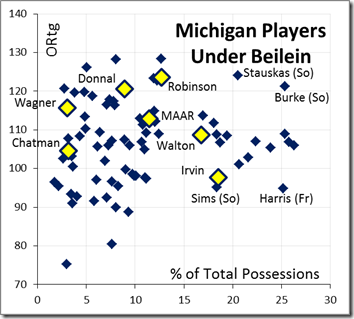

While there were some notable highs – Zak was the best player on the floor in wins against Purdue and Maryland, and he hit a couple huge late-game shots like the one gif’d above – there were struggles as well. Because of his low shooting percentages (over three-quarters of his shots were jump shots, which had an incredibly low eFG% of 41.9%), his efficiency numbers were dragged down, and were the worst on the team:

But, as the chart shows, Zak used more possessions in sum than any other Wolverine. While his usage rate itself wasn’t abnormally high, the sheer amount of minutes he played drives his total contributions close to what you would expect from your lead guy – or at the very least, to within the range of the most critical of your offensive pieces. As you can see, Irvin is near the bottom of the pack efficiency-wise of those types of players.

[After the JUMP, how Zak handled the alpha role]

63