zone keeper

I mentioned this earlier in one of the two instances where I brought up Chris Brown's explanation of the differences between inside and outside zone runs. Here's a play featuring the tell a couple coaches suggested I look for when I was complaining about the difficulty of distinguishing between the two.

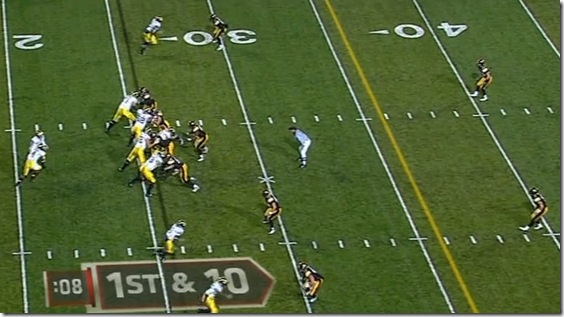

Michigan's in a shotgun with trips to the right. Two things to note here are the two deep Iowa safeties, and the shift of the Iowa linebackers outside. Angerer, the MLB, is lined up over Odoms, sort of:

Also, Greece has destroyed Latvia in World Cup qualifying.

The thing to note in the above frame is the position of Forcier relative to Minor. Forcier is a yard or so in front of his tailback. For comparison, here's a play against Indiana that would end up a standard zone stretch:

Forcier is a yard behind the tailback. This allows the RB to come across him at speed and get to the frontside creases the stretch looks to exploit.

Back in the Iowa game, the positioning of Forcier allows Minor to take a handoff already headed upfield, which was one of the adjustments that Penn State struggled with so badly last year. Also note a great oddity:

Michigan is blocking the backside defensive end! Why are they doing this? Well, if you don't block him and he crashes down and you're running a play that's anything short of a stretch play that's running away from him there's a good chance he makes a thumping tackle in the backfield. Michigan did this a lot against Iowa because Brandon Minor's RAGE is most effective when he's heading straight upfield.

Another item to note: at the moment of the handoff, Forcier is staring at the MLB over Odoms, judging whether or not he's coming up to contain.

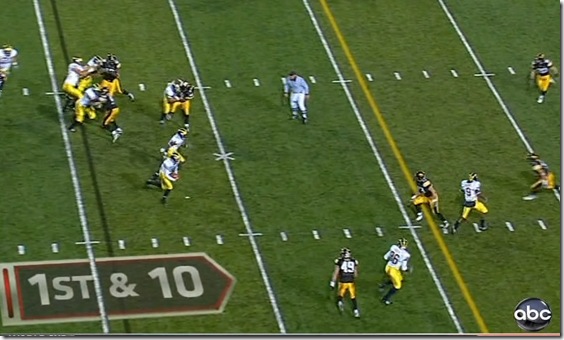

He isn't. And one reason for that may be that this looks like play action. Odoms isn't running a bubble. The backside defensive end is getting blocked. In the past, this has always been a pass, or an attempted one. So Angerer gets a pass drop. By our next frame he'll be hanging out at the first down line, six yards back from the frame above:

You'll note that Minor is running right next to Forcier; with five guys in the box and no support for a hypothetical bounce, Minor could have made this same run. Iowa's decision to leave two deep safeties back makes it really hard for them to stop Michigan's ground game, though it did prevent Michigan from breaking anything long: their longest run in Kinnick was twelve yards.

At the end of the play Forcier has near first down yardage after having slid to the ground untouched. The Iowa defender does give him his best Cato June, though:

Here's the glorious you-tube-o-vision, in which you can see that the receivers' half-hearted routes. That indicates this was a called run play, not an improvisation, in case you're wondering if this was play action gone awry (awright?):

Object lessons:

- Zone runs have a bit of a tell. If your depth perception and processing is quick enough and you see the QB step forward you've got a good idea that it's not a stretch. If he stays back you've got a good idea it is. This is probably not a huge deal since the QB takes up his final position moments before the snap, preventing—or at least hindering—the ability for defenses to key on it. It's a lot to process that when you're trying to time the snap and figuring out your assignments and whatnot. It is there.

- But you, the viewer, have a great view of it. TV angles are great for picking this out, though, and it's simple enough that you can try to pick it out real-time.

- RAGE. Michigan went to a lot of interior, non-stretch runs with Minor and blocked the backside DE. This helped out on a variety of plays and should hypothetically make Forcier's job on the reads easier because the guy he's reading is a lot further away and his motion has to be less subtle if he's got contain. This also brings in some elements of Paul Johnson's flexbone, too. Johnson loves to leave a guy unblocked for much of the game, then crush him unexpectedly for a big play.

- Michigan's mixing up its routes on certain keeper plays. I'm betting that if Odoms ran a bubble route on this play that was a key for one of the linebackers to shoot up for contain against Forcier and for one of the safeties to crash down on the bubble. By just running its receivers downfield, Michigan got Iowa to go into pass drops and opened up tons of space for Forcier.

- Iowa loves them some two-deep safeties. The zone read brings in the quarterback as another runner and has essentially forced its opponents to ditch the two-deep look. In the Rodriguez coaching videos kicking around the web, the implicit assumption is that opponents will usually have a single deep safety because of the threat of the keeper. Iowa defies that, and it worked for them, albeit barely. Michigan racked up almost 200 yards on the ground without its starting center and nominal starting tailback despite seeing five drives end on turnovers. Michigan had similar success against Notre Dame last year when Corwin Brown decided to keep two deep safeties. Once Michigan emerges from its freshman quarterback purgatory I wonder if Iowa will be able to get away with this sort of thing.

28