FF210

Previous Classes

FF 101 - The Fundamentals: Syllabus & Day 1 (Overall), Day 2 (Offense), Day 3 (Defense), Day 4 (Offensive Line), Day 5 (Wide Receivers)

FF 201 - 3-3-5 Defense: Day 1 (Advantage/Disadvantage) (I still believe this), Day 2 (Against tight formations)

[ED: PGB - I took the liberty of adding each of these courses to the MGoHallofFame: http://mgoblog.com/content/user-curated-mgohalloffame. ED: bump.]

FF210: Screen Package

Whatchya know, I still exist. That’s right, I’m like either Santa Clause or the red M&M in that commercial. If you haven’t been here for more than a year, or worse yet, if you have a life outside of here, then you either don’t know or don’t remember about the series above. I’m formerly [name redacted] and am now a Space Coyote (deal with it, mostly because a Space Coyote from Space is awesome), and I’m going to do a slight continuation of the previous series. Heck, let’s call it FF210: Football Packages. Rather than talk about what the title suggests (wrong website), I’ll add this little section about screen packages. Other classes could include: blitz packages, coverage packages, bunch formation packages, etc. The fun could be never ending.

(Aside: If you’re wondering why the previous series seems a bit incomplete, like “where’s the defense?” it’s because it is incomplete. If you’re wondering why I didn’t finish it…yes. Also, I’ve been a bit busy.)

Lately there has been much confusion about screen type substances around these parts and I figured I would be a bit of a guest professor for a second and teach a few things. If you are looking for how to install a screen door, this is not the place for you, so I’ll just let Menard’s do that for you.

Introduction

Not all screens are created equal. And as they are not all created equal, they are also not all designed to take advantage of the same things. There is a lot in common with many screen passes, but there are also key differences. There are lots of different types of screen passes, and I’m not going to cover them all. What I will cover today is probably the more fundamental screens. The discussion below will consist of what these screens are attempting to constrain (“constrain play” has become a favorite word around here), what the keys are to the type of screen, and how to successfully run the screen. Note, as I said above, there are many, many more screens out there that I won’t cover. There are also many variations of these screens that I won’t begin to touch. This is only meant to be an introduction to these basic concepts. The types of screens included are:

1. The ones where you throw to the WR, we’ll call those WR screens

- Bubble Screen

- Tunnel/ Jailbreak Screen

2. The ones where you screen to the RB, we’ll call those RB screens

- Slow Screen

- Crack Screen

Screens not covered: middle screen, TE screen, throwback screen, transcontinental (even though it’s a crowd favorite), etc.

Screens in College Football

In college football linemen can block down field at the snap as long as the pass play is completed behind the line of scrimmage. This is not the same in the NFL, but is a big reason why screens are so successful at the college level.

Wide Receiver Screen

Just because you’re throwing a screen pass to a wide receiver doesn’t mean it is in an attempt to do the same thing. There are two main types of WR screens that I will discuss, and each have very different keys and are constraints of different things. They are the bubble screen and the tunnel/jailbreak screen.

Bubble Screen

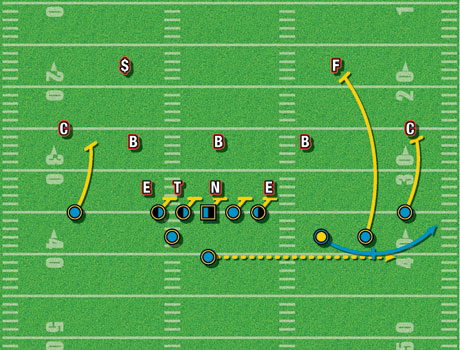

Better image with some play action

mgoblog bubble screen picture paged

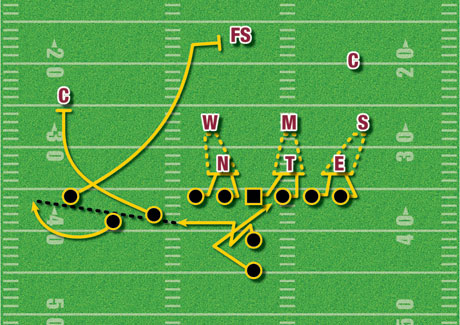

Against Michigan!

Constraint:

This is essentially a run play constraint. The bubble screen is intended to strength the defense horizontally. It is an easy way to reach the edge without a clumsy pitch out of the shotgun. It is typically run to get defenders out of the box. It takes advantage of defenders peaking into the back field and reacting quickly and out of control to flow. Gap sound teams with safeties in the box with responsibilities in gaps will have trouble on bubble screens because they are not stretched horizontally and are focused on the play in the backfield.

Running the bubble screen will:

Running the bubble screen will open up lanes in the middle of the field as defenders must flex from sideline to sideline. This will give gaps for RBs/QBs on Zone Reads, RB power, and QB draws. This also opens up the deep middle of the field by often forcing safeties to play off the edge of the line rather than in the box as linebackers or OLBs out of the box to respect the sideline threat more. This makes it much more difficult for defenders to play both the run and the pass. If run correctly it will leave a WR one on one on a corner in space, or better yet, with both corner taken out of the play and a score up the sideline.

When to run it:

Typically you run it when corners aren’t pressing. If corners are pressing the pass can become very dangerous. More importantly, you run it when safeties and LBs are shaded too far inside in an attempt to play both run and pass. The danger: make sure the corners respect routes enough to not quickly jump the bubble.

How to run it:

It’s not as simple as just taking a snap and winging it out there. As I have been told before, a QB throwing a bubble screen is kind of like a short stop turning a double play as far as the importance of footwork, body position, grip, and not rushing.

Most of the time in the backfield there is some sort of zone read action. This means that the play looks like a zone read it terms of what the running back is doing. The process of the QB adjusting the ball and throwing means that an actual playaction is really necessary. What is so different about the bubble screen is that it doesn’t typically require linemen to block for a “screen”. The linemen also carry out the zone read play. This causes LBs and Ss to flow down to play the zone read, leaving the WR open on the edge.

The blocking WRs come off on the snap as if they are running routes. His job is to take the nearest threat, which is mostly the man covering him. As they converge on the man covering them, they square their bodies and force and get their backs to the sideline, blocking those covering them to the inside and leaving a lane down the sideline. If the defender does manage to get outside, continue to drive him to the sideline (this isn’t O-line blocking, there is a lot of space and the ball carrier will run off the blockers butt to the hole in the defense regardless). In most cases the WR blocks the man head up on him (or the man that appears to be covering him). In some cases the WR will crack down on the defender covering the screen receiver. It all depends on how the defense plays it at the snap. The reason that the WR usually blocks the man covering him is because it causes traffic for the inside cover guy to have to get through. You can, in essence, block two guys with one blocker, leaving a seal down the sideline. Some people crack the inside guy and hope the outside cover man follows inside, but you run the risk of the outside guy reading the play and blowing it up. All these decisions must be made based on the defenses alignment.

Clip:

Oregon. The first one suffices (some of the others aren't really bubble screens). Note that they double the near man to the second corner. The second corner jumps outside and the WR kind of just blocks him straight up, making this play a first down rather than TD. This can be done with 3 or 2 WRs.

[Ed: others after the jump.]

26