adj. points per shot

John Beilein likes to say that the best defensive rebound is one by his point guard. Why? That's the best way to get out in transition. I decided to investigate Beilein's claim—at least as it applies to Michigan—by going through this season's play-by-plays and charting each defensive rebound.

In the (chart?) chart below, I've tracked each defensive rebound as well as any resulting fast break field goal attempts or drawn shooting fouls—a fast break, in this case, being defined as any shot coming within 10 seconds of the defensive rebound, so long as the ball remained in play the whole time. Also in the chart is how often each player gets a fast break assist or made basket off their own defensive rebound. "% Opp" is the percentage of individual defensive rebounds that result in fast break field goal attempts or drawn shooting fouls, and "% Conv" is the percentage of made fast break FGA and shooting fouls drawn.

SPOILER ALERT: Beilein's theory is correct.

| PLAYER | Def. Reb. | FB FGA | FB FGM | Assist | Self Make | FT | % Opp | % Conv |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hardaway | 76 | 33 | 16 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 47.4 | 25.0 |

| Morgan | 56 | 20 | 14 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 37.5 | 26.8 |

| Robinson | 56 | 18 | 12 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 32.1 | 21.4 |

| McGary | 54 | 25 | 14 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 48.1 | 27.8 |

| Stauskas | 49 | 25 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 53.1 | 34.7 |

| Burke | 42 | 23 | 11 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 59.5 | 28.6 |

| Vogrich | 13 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 46.2 | 46.2 |

| Horford | 13 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15.4 | 7.7 |

| Bielfeldt | 12 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50.0 | 16.7 |

| Albrecht | 10 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30.0 | 0 |

| LeVert | 7 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 42.9 | 0 |

| Akunne | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 33.3 | 16.7 |

| McLimans | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20.0 | 0 |

| Person | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TOTAL | 400 | 166 | 92 | 18 | 18 | 8 | 43.5 | 25.0 |

Some takeaways:

GOOD PLAYERS ARE GOOD

Trey Burke is far and away the best on the team at turning defensive rebounds into transition opportunties, and the reasons are two-fold. For one, it's Trey Burke—you know, the guy you want running the fast break. Second, as you can see in the video at the top of the post, as a diminutive point guard many of Burke's rebounds come on shots that carom far away from the basket, providing a better chance to turn and run than a rebound in the charge circle.

Burke is also the best at converting his own rebound at the other end, with—surprise!—Tim Hardaway Jr. second in that regard; both have seven made baskets off their own rebounds while Hardaway has one more free throw opportunity... off 34 more defensive boards. Though Burke converts at a higher rate, Hardaway has the highest defensive rebound rate on the team by a non-center, and you can see just how valuable his newfound dedication to that area is to the team.

MCGARY'S OUTLET PASSING

Jordan Morgan (and, in small sample size territory, Jon Horford) has a rate well below the team average when it comes to turning defensive rebounds into transition opportunities, which is understandable: as a center, he's not turning and leading the break, and most of his boards come from right under the basket, where it's hardest to spark a transition opportunity.

That makes McGary's ability to turn 48.1% of his defensive rebounds into fast break chances—a better rate than Hardaway—all the more impressive. The difference, as far as I can tell, is in McGary's outlet passing; he's got surprisingly good court vision, which allows him to turn quickly off a rebound and find his point guard. This is one area where McGary has a decided edge on Morgan, especially since his defensive rebound rate is also higher.

GAP BETWEEN FRESHMEN: NOT THE ONE YOU'D EXPECT

What surprised me most when putting this together was the gap between Nik Stauskas (53.1% Opp) and Glenn Robinson III (32.1%). While Robinson matches up against bigger players, ending up closer to the hoop for rebound opportunities, he's also the more athletic of the two. It's Stauskas, however, who's the only player besides Burke to crack 50% in major minutes—this despite rarely being involved in the play at the other end of the floor.

Perhaps there's a lot of noise in these numbers given the sample size (I'd say yes—I'm mostly ignoring the "% Conv" figure because of this) but that doesn't entirely explain that large a gap. Like with the big men, I believe this has to do with the difference in court vision and passing ability; so far this season, Stauskas has proven himself the more adept passer. Meanwhile, Robinson still seems to be adjusting to the college game; in a year, I'd bet his transition rate will be better than Jordan Morgan's.

[Hit THE JUMP for an update on the Kobe Assist and Adjusted Points Per Shot numbers from last month.]

All missed shots are not created equal.

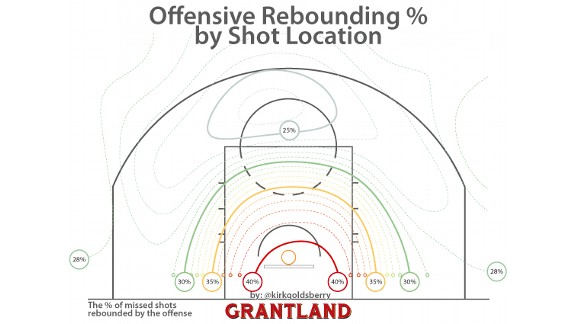

That's the premise of this article by Grantland's Kirk Goldsberry, who examines the work of the NBA's foremost volume shooter, Kobe Bryant, and comes up with a very interesting new statistic. The background [emphasis mine]:

[J]ust like shot outcomes, rebounding outcomes also depend on who is shooting, where they are shooting from, the stratagems of each team, the rebounding abilities of each player, and the precise spatial configuration of the 10 players on the court; as a result, there is a less apparent tenet of basketball: All missed shots are not created equal, and their DNA is inherently dependent upon their ancestral events — some missed shots are good for the defensive team, and some benefit the offense, as many misses actually extend offensive possessions with the proverbial "fresh 24."

Goldsberry coins the name "Kobe Pass" for any shot that is rebounded by the offense—an individual statistic for the shooter, as offensive rebounds is obviously a stat that exists. This leads to the "Kobe Assist":

In fact, league-wide, 34 percent of the time Kobe passes results in points right away because the recipient of the Kobe Pass, a.k.a. the offensive rebounder, frequently scores immediately after acquiring the basketball. In such cases, I define the Kobe Assist as an achievement credited to a player or a team missing a basket that in a way leads directly to the kind of field goal generally referred to as a put-back, tip-in, or follow.

In case you haven't caught on, Kobe Bryant is the master of the Kobe Assist, putting up the best numbers even before the Lakers brought in rebounding force Dwight Howard (having Pau Gasol and Andrew Bynum helped, of course).

While Kobe Assists depend in no small part on a player's supporting cast—the guys going up for the rebound, especially—there is still an art to their creation. Much of this has to do with where on the floor a player takes his shot; as a general rule, the closer to the basket a shot originates, the more likely an offensive rebound will occur:

There is one notable exception: three-pointers are rebounded at a lightly higher clip than long twos. This is an NBA chart, so the stats for college may be slightly different, but the point remains that long twos are the worst shots in basketball—often a waste of possession not only because of their low-percentage nature and lack of the upside of a potential extra point, but also because they're usually the last shot of a possession.

[Hit THE JUMP to see the best Wolverines at producing Kobe Assists as well as a new advanced metric, adj. points per shot]

10