What Is: Gap Blocking vs. Zone

[Dr. Sap]

[This is a work-in-progress glossary of football concepts we tend to talk about in these pages. Previously:

Offensive concepts: Run-pass options (RPOs), High-low passing routes, Covered/Ineligible receivers, Blocking: Reach, Kickout, Wham

Defensive concepts: Keeping Contain/Lane Integrity, Force Player, Hybrid Space Player, One-Gap Fronts, Scrape Exchange. Coverages: Tampa 2, Pattern-Matching, Quarters and how MSU runs it

Special Teams: Spread punt vs NFL-style]

------------------------------------------

Depending who you ask there are either two or three or sixteen thousand different blocking schemes offenses use to puncture run lanes into a defense. If we cut out a few exceptions, and a lot of variants, you can boil them down to two basic philosophic schools: Zone and Gap.

(And man, and hybrid, and zone can be split between outside/inside but shut up).

Harbaugh, as you might have heard, is one of if not the ur gap coach in football, as is his top lieutenant Tim Drevno. New tackles/tight ends coach Greg Frey, as we’ve mentioned twice this week, is not just in the zone camp but is one of the chief practitioners of its outside zone wing.

What’s the difference, and why does it matter? I’ll show.

HOW GAP BLOCKING WORKS

“When badly outnumbered he managed, by swift marching and maneuvering, to throw the mass of his army against portion of the enemy's, thus being stronger at the decisive point.” –description of Napoleon battle tactic

This is the football’s fastball: I’m coming towards the plate so fast and so hard that by the time you know where it’s going you can’t catch up. To use a war metaphor, gap philosophy is about picking a spot in your opponent’s defenses, puncturing a hole, and sending as much material into it as possible as quickly as possible before the defenders can match it.

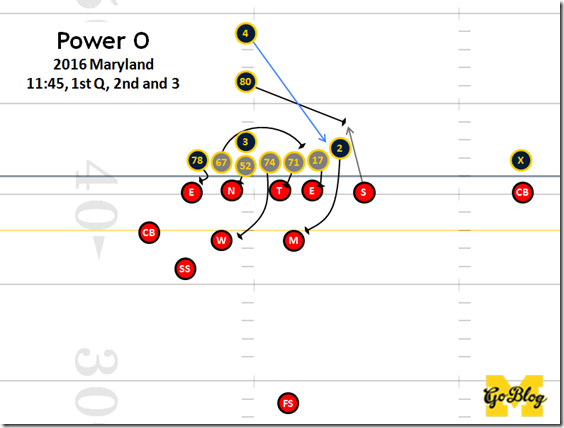

The above formation is unbalanced, which did its job in getting the defense to leave a cornerback and safety to a side with zero receiving threats (Mags is ineligible by number). The fullback has a kickout block on the SAM linebacker. Kalis pulls, Asiasi picks off a linebacker, and Deveon Smith gets a 300-pound escort through the gap between Wheatley and the back of Khalid Hill. That gap is the gap they planned to attack, and the most likely one to become available.

That it won’t always be available is what makes gap blocking go from very simple to highly complicated. The great power teams know how to adjust on the fly to defenders diving into the important gap, for example on this play if the SAM is coming inside hard Hill might arc outside on the fly, seal the SAM inside, and hope Smith and Kalis adjust to earn a big run. Or what if that Mike linebacker blitzes the gap inside of Wheatley? Or the whole dang defensive line slants playside? In general the OL will do their best to not let that happen and adjust (e.g. Asiasi might have to assist Wheatley, or the puller might kick out an unblocked end discovered at the point of attack).

I think you get the gist. Gap blocking has everybody working to widen the chosen gap and get bodies attacking that gap as soon as possible. Emphasis is on overpowering—as you see here this play works mostly because Ty Wheatley Jr. latched onto the playside defensive end, and rode him downfield.

[Hit THE JUMP for Zone]

HOW ZONE BLOCKING WORKS

[OZ Resources: Eye of the Tiger’s diary, Smart Football, Roll Bama Roll, FishDuck (Oregon), BTSC (Steelers) Mile High Report (Denver Broncos), how to Mike.]

“Don't exploit your enemy's weakness, for he may have none.

Exploit his passions and the battle is yours.”

― George Norman Lippert

If gap blocking is a fastball, zone is a nasty cutter—thrown correctly inside or outside it works against any hitter, because the worst thing you can do against it is over- or under-react. Zone runs threaten multiple gaps all at once, and challenge the defense to stay responsible in their gaps while getting blocked. Rather than the OL having assignments as a whole, each lineman is responsible for blocking whatever player is coming into his zone.

What he does depends on how the defender is playing: if the defender is trying really hard to get across his blocker—something you cannot allow in gap schemes—a zone blocker will not only help him to his new gap, but assist him. Hell, throw him. Give him a good oomph until he’s in your buddy’s zone, then seal the next guy coming and now there’s a gap.

On the other hand if a defender is shooting vertically inside you, seal him in there, and the RB has somewhere to cut to:

Inside Zone is the less extreme version, and Michigan ran it plenty (notably for almost an entire drive against Penn State). The OL step down into their blocks and try to win an old-fashioned drive-block, then react to whatever the defense does to react to that. Inside zone often double-teams interior linemen and lives on combo blocks to get to the linebackers.

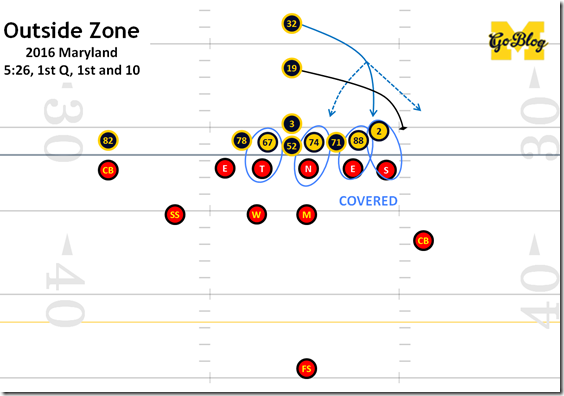

Outside Zone takes it further, having the OL release with a slide step (still facing the defense) to hopefully outflank the defenders. Ultimately someone will make a wrong move and get blocked where he shouldn’t be, and that’s when the RB cuts to his hole. OZ is slower to develop and quick to end up in the backfield if a block is missed, but the tradeoff is with the whole front moving there are more gaps the RB can access.

They figure out whom to block mostly by alignment and who’s being “covered” (unable to release because there’s a guy in your way) by the defensive front. Covered linemen will have to deal with the guy over them, either by comboing him or seeing that your buddy will pick him him, or else this happens:

Bad Kyle.

On a defensive slant it’s each offensive lineman’s job to ID it and deal with the next guy to show in his zone. Uncovered linemen can do different things: double-team and try to get over (reach) the guy lined up playside, combo that guy so the covered OL playside of you can get out to the next level, or if that’s not going to work, release downfield and try to pick off a linebacker.

Here’s the first play (from the Maryland game) again, which I drew up to show how the thought processes:

This play Maryland showed an under2 front, covering both TEs and the playside guard as well as the backside guard but leaving the center and tackles uncovered. It’s a good adjustment: If Michigan tries to attack that frontside C gap with Power again they’ll find a DT following Kalis into the backfield while the point of attack has been reinforced with a heavy SDE. But Michigan isn’t sending everybody at one chink. The plan this time is engage, lightly probe, and wait for an enemy unit to do something rash.

Here’s that play again in slow-motion. Watch as the playside DE does something rash:

So on this play Braden read that the DE was shooting outside of him: not his problem anymore, move on to the next guy. This is why zone is so killer: the defense does just ONE aggressive thing and they’re about to be punished for it. Except Poggi went for the same guy, hit Braden, and left an unblocked guy in the hole. This is why Michigan was bad at zone this year: the players weren’t used to all of the wrinkles yet.

Watch it again, but this time focus on Cole. Getting out on that MLB takes some athleticism. Staying in front of him required more than Cole has, however even once he’s lost the battle Cole gets a good shove to maybe end that MLB’s chance at stopping a hypothetically free Isaac.

There’s a lot in there so yeah, this isn’t a blocking scheme you learn overnight. However it’s not THAT technical to pick up, and after about a year of doing it together a line is likely to start getting comfortable with the tendencies of those around them and be able to anticipate what the defense is throwing at them, and react accordingly.

-----------------------------

There’s a third right?

HOW MAN BLOCKING WORKS

Man blocking isn’t usually a base philosophy, the way a changeup wouldn’t work as a base pitch. The above is an ISO in principle but with the fullback arcing into an outside gap, plus some WR motion and a pistol zone-read look to widen out the space they’ll be running into. With the DL shifted over, Michigan’s linemen were in good position to block down on the defense’s meat, and Poggi can get across his linebacker to give Evans a place to go.

-----------------------------

WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE?

Gap blocking is probably harder to run, but when consistently run well by players who can overpower their opposition, it’s also the hardest to stop. This is why the classic gap-blocked play, “Power O”, continued to dominate the upper echelons of college football for a decade after zone was widely adopted, and well into the spread era. Power O today is not only back, but so beloved by coaches it gets the holy sobriquet. Ian Boyd:

If you ask most coaches across the country what their favorite play is you'll often hear back "power" which is often just referred to as "God's play." The play is ideal for how it offers a physical, hammering answer for any defensive problem while also setting up the best play-action opportunities of any running scheme in the game.

I recommend the whole article. The reason Boyd says gap-blocked running is so nice for play-action is the best way to beat it is have the linebackers screaming upfield if they sense someone is releasing onto them. That opens up all of those passing lanes behind the backers, while the reactive first-level defenders tend to create a nice comfortable pocket for deep play-action passing.

|

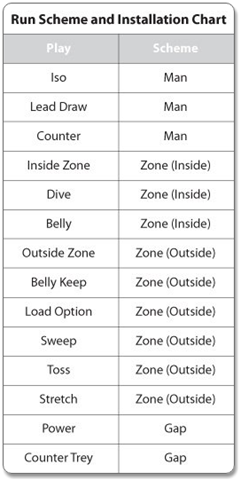

| Handy-dandy chart of some typical blocking schemes for playtimes, courtesy X&O Labs |

Zone blocking is about reacting to the defense and making them wrong no matter what they do. In course its practitioners are decidedly less evocative in singing its praises. It makes that up and more in effectiveness at the highest level. In the last 20 years the NFL—which has no shortage of athletic mutants on both sides of the ball—has tended to favor zone blocking so much that Harbaugh’s schemes found defenses relatively unpracticed at defending it.

Zone is also lower rent overall. Zone can get away with smaller, more agile players, while a gap-blocking scheme is rendered inert if its point men can’t create movement on defensive linemen. Gap blocking offenses, with relatively simple assignments for some guys, can tend to get away with one or two unpracticed guards if the center tells him what to do. Getting him to the point where he can confidently go off script however often takes years. Conversely zone linemen are major liabilities until they’re ready to read and react to defenders correctly most of the time, but they’ll get the hang of it faster.

Both require high intelligence—other than quarterback there probably isn’t a major sport position that requires as much headiness as centering an offensive line regardless of your base blocking scheme.

WHY ARE THERE ZONE VERSUS GAP COACHES?

Coaching gap blocking involves a lot of focus on generating leverage and power, and the tactical coaching has a heavy emphasis on identifying fronts and all the weird things the defense can do to screw up your assignment. It also emphases different skills in different linemen. On this play Braden just has to drive and seal a tackle, which takes a lot of muscle and leverage and handwork, while Kalis has to pull, get to the hole, ID what’s there, and make whatever block his RB thinks he will make, the choice in target being more important than perfect contact. Also crucial to gap blocking is a center (or at least someone) who can ID the defense’s front and call it out so everyone else can pick their correct man.

Coaching zone will place a greater emphasis on footwork (which if you’ve ever known a gap coach this is really saying something!). There’s also a bewildering number of techniques to teach, as each guy has to learn to deal efficiently with all the things an engaged defender might do, plus their combos.

College coaching is a race against the clock, so teaching these disparate skills often comes down to who can distill it and package it in a way to instill it quickly and effectively. Most coaches I’m sure already know how to run the other one, but knowing how to run something and knowing how to coach it is the difference between knowing how to drive a car and being able to teach a 16-year-old to do so in a few hours. So OL coaches tend to specialize as they perfect a method of teaching their favored (or their boss’s favored) schemes.

As you can see by the two Maryland plays, Michigan would love to be able to run both, as outside zone can be a devastating counter to the things that defenses do to stop Harbaugh’s bread and butter. Greg Frey has been hanging with the up-tempo outside zone-iphiles going back to helping launch USF’s program way back in the day (Rodriguez plucked him from there in 2007). Having him duplicate Drevno’s efforts makes little sense right now, but Frey is probably going to be way better at coaching the players on zone technique.

January 27th, 2017 at 2:34 PM ^

January 28th, 2017 at 6:50 PM ^

when the OL is winning, there are also more gaps for the DL when the D-Line is winning.

Remember USC in the 2006 season Rose Bowl.

January 27th, 2017 at 2:37 PM ^

Come for the football, stay for the Napoleon strategy link to learn something completely different! :) :) :)

January 27th, 2017 at 2:41 PM ^

January 27th, 2017 at 3:43 PM ^

January 27th, 2017 at 3:48 PM ^

But think of the long-term benefits if they learn it while they are young. Ideally you have OL sit out a year, learn and get stronger. We don't have that luxury... yet. But next year, and the year after that. Look out.

January 27th, 2017 at 2:50 PM ^

Good stuff (I think). I've internalized about 1/3rd of it and feel like I know a lot more than I did, despite watching football for a long time. Keep this stuff coming.

January 27th, 2017 at 2:58 PM ^

Thank you. But I found all this already in Sun Tzu's "Art of War." For example:

"If the SDE is aggressive, trap him. If the SDE is timid, smash him."

It's on page 32. I guess there's never anything new in football.

January 27th, 2017 at 3:10 PM ^

January 27th, 2017 at 3:40 PM ^

this post is dedicated to the asshole who castigated some poor commenter a couple days ago for asking seth for this exact breakdown

January 27th, 2017 at 3:41 PM ^

January 27th, 2017 at 4:10 PM ^

I think you have to be able to run some combination of both zone & gap/man blocking. If my local HS coaches play a team that on film only blocks zone, they quickly adjust by having the defensive front stand & read. DO NOT try and get upfield, engage only if engaged by a lineman,otherwise scrape along with the play and wait for them to make the first move so to speak.

This allow LB's to also read and follow, only attacking once the O commits to a seam.

The only way to punish a Defense for this(in the run game) is to switch and hit them with power(gap) and slam the ball down those reading lineman's throats because their initial technique puts them already behind the proverbial 8 ball.

I see defenses in CFB doing the same thing. Watch our D front vs. OSU this season and its very similar to what I described above.

basically if you're O line is NOT going to fire OUT into us and inititiate contact then why should we be your suckers & over commit ourselves? We'll just hold ground, watch the flow of the play and make you bust the first move while we all maintain our spacing as we flow playside. Think of it as gap integrity to a moving gap or...basketball on grass.

The trick is getting the D front 7 players to slide playside while maintaining their alignment with the frontside hip of their gaps backside blocker to protect against the inevitable cut back lane that appears if you get too far playside while keeping their eyes playside watching for which one of those zone blockers is going to commit upfield.

Watch the maryland clip above and you can clearly see the 2 defenders who penetrate(for no reason whatsoever) and over pursue playside which creates the lane the puts Isaac 3yds deep w/ only a linebacker to beat. If those guys just stay on their side of the LOS and scrape along w/ the O lineman, giving him the playside advantage(OLB has to become the force defender) they string that play to the sidelines for no gain.

January 28th, 2017 at 1:22 PM ^

Comments