Mathy Mailbag!

Apparently, this was the worst showing by U-M in the draft since 1994 when Derrick Alexander was the program's only player selected that year. People are using this as further evidence that the cupboard was bare when Rich Rod arrived on campus (as if anyone paying attention needed more evidence). But one draft doesn’t tell you much about the talent level of a particular team. For example, that 1993/94 team still finished 7-4 and 23rd in the Coaches’/AP. Why? Well, because that team also had three players who would be selected in the first round of the 1995 draft, and five players overall. If we want to know how bare the cupboard was when Rich Rod arrived, we also have to look at the 2010 draft. So, of the current players eligible for the draft next year, who other than Graham is likely to get drafted? What’s the fewest number of players drafted from a major program over a two-year period? Does this tell us anything about Rich’s cupboard that we didn’t already know? Obviously, it was bare but was it far worse than people realize compared with other major programs?

--Matt

U-M/1995

Yikes. A quick combing of Michigan's roster comes up with the following potential 2010 draftees outside of Graham:

- Greg Mathews: maybe a late pick? He doesn't have the speed to go very high.

- Minor/Brown: it's too early to tell with either but both have the raw physical ability to be drafted somewhere decent. One seems like a first day pick with the other going later.

- Ortmann/Moosman: probably not drafted.

- Stevie Brown: Lions first rounder.

- Zoltan The Inconceivable: likely to be the first punter off the board, whenever that happens.

So, yeah, it's Brandon Graham, a couple running backs, and the space punter. I don't know what the fewest number of players drafted from a power program over a two-year period is, but that's probably not the right question. The right question is "how many teams with like one high NFL draft pick and three or four mid-round picks are any good?" and the answer is "none, but there are plenty that didn't go 3-9."

This following one concerns variance, as discussed in the earlier post on Gladwell and basketball and Carr and the non-scoring offense. It's long, so I've chosen to respond after each paragraph. Though this looks fisk-y, it's not intended to be confrontational.

Dear Brian,

Your recent blog entry, detailing variance, risk versus reward, defense, offense and modern versus older systems, beginning with a basketball analogy, seems correct, but I have some issues. Your presumption seems to be that solid defense allows for a brute strength, low variance offensive strategy, in the style of Bo, and likewise with Carr. At the same time, however, you insinuate that a slow, grinding offense that keeps the other teams’ offenses off the field is of a critical nature towards that end.

I was not entirely clear about my thinking here. I do think that a really, really good defense allows for that sort of offensive strategy, and more specifically makes the run-run-probably-run-punt style of closing up a game make sense. In that sort of situation you're playing towards your strength.

However, when your defense is mediocre and you have a future NFL player at quarterback, shutting up shop and hoping your mediocre defense comes through is playing to your weakness. Carr did this a lot, if we're expansive about the word "mediocre".

As far as what sort of offense you want at the end of the game, yes, the sort of offense that can grind out a first down is nice to have, but if you don't have that offense—and not many do when they opposition is selling out like mad—you're doing yourself a disservice. There are specific situations where grinding it and punting makes sense, but none of them come with more than two minutes on the clock.

This is reasonable, as you can’t rely on a small lead and a low scoring game if you can’t keep the other team from scoring. The problem, however, comes in making the assumption that defense can’t be, or at least wasn’t, considered a weapon. Absolutely, using a prevent defense, clogging the running lanes, and keeping opposing offenses to short, clock eating runs between the tackles works towards that end. But what of the Michigan defenses through the years, especially in the early Carr era, that actually produced more variance, not less? Sacks, fumbles, and interceptions all increase variance in a game. Sudden turn-overs and backward yards are not supposed to happen on an offensive possession. I would say that in as much as a thundering, slow moving, ground based offense is designed to reduce variance, keep games simple and allow dominant talent to win out; the same strategy of good fundamentals (tackling, stripping the ball, pass coverage) has the exact opposite effect, creating lots of variance and unexpected.

Your definition of "good fundamentals" on defense varies from mine. When I think of good fundamentals, I think of a two-deep shell, minimal blitzing, and conservative strategies. Bend but don't break sort of things. A defense heavy on the blitzing and light on deep safeties is more prone to wild swings. And many of the things you cite as good fundamentals are zero-cost activities from a strategic standpoint: tackling, forcing fumbles, etc.

It seems that you’re positing that the more an offense scores, the more variable and therefore less predictable a game becomes. I think that’s the exact opposite of the truth. Offenses are supposed to score. To assume they will do ANYTHING but that is fallacy. I think the variance comes in when they fail to. Therefore, I don’t think that Bo’s and Lloyd’s game plans were low variance at all. I believe they simply tried to keep the variance, the sudden swinging changes, to one side of the ball. After all, if your defense FAILS to produce variance, the worst that will happen is the other team will score. That can be recovered. If your offense does produce variance, then the worst that will happen is you will lose your chance to score back. You can’t get that back.

This wasn't what I was getting at, but it wasn't the opposite of it either. What I was trying to say was this: all other things being equal, I'd rather Michigan play a game where both teams have sixteen possessions than eight. (Assuming that they don't suck, of course.) Michigan's more likely to come out on top in that situation. The way Michigan played under Lloyd, however, seems like it lent itself to a lot of long drives on both sides of the ball and generally depressed the number of possessions.

Simplified – You’re saying that offenses produce variance by moving quickly, scoring. As talent entropy occurs, this is harder and harder to stop, and so Bo and Lloyd saw their wins weaken, because their goals were to reduce variance. I believe that defenses produce variance by preventing scoring, and scoring on defense. We saw less success against higher level and middling teams in the last few years because talent entropy, and the coinciding spread of more complex, harder to stop offenses, has leveled the playing field, reducing defensive variance.

Different song, same title.

Thank you,

Eric Fischer

Okay, to properly address this we need to bring in variance's buddy: expectation. In layman's terms, expectation is the average of all expected outcomes. When you roll a die the expectation is 3.5. When you kick an extra point the expectation is 0.98. Variance is a measure of the average difference between trials. I could kick up the variance of the dice roll by turning 1 into –101 and 6 into 106 without affecting the expectation. I could kick it down by weighting it so that 3 and 4 came up twice as often as other rolls.

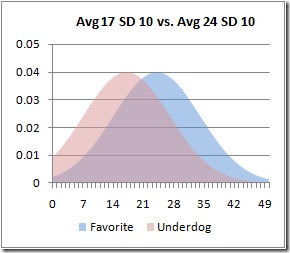

If you expect to win a game, variance is your enemy. I'm going to borrow some graphs from the excellent Advanced NFL Stats to demonstrate:

So here we've got two teams with the same variance in their play, one of which is a touchdown favorite. The underdog has about a 31% chance of winning.

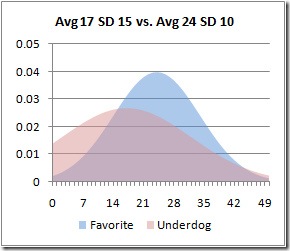

Now the underdog has gone mad, probably going for it on fourth down a lot, inventing and deploying something called HELICOPTER PUNTING, and trying to block every extra point. They get blown out a lot more but also win more: 35% of the time.

This effect is powerful enough to overcome reductions in expectation:

But this time the underdog’s average is reduced from 17 to 16. The increase in variance still results in a slightly better chance of winning despite its overall reduction in average points scored. In this case, it's 33.2% for the underdog.

And it's the same for the favorite and reducing their variance: sometimes it's worth reducing expectation to get it, but only in certain situations and when you're a considerable favorite. In Bo's time, Michigan was a considerable favorite much more often and the game lent itself to low-variance moves: a 40-yard punt is much more valuable in an era when ten points is a potentially game-winning number.

Anyway, to the assertion above: modern offenses have more variance to them* because they score more. Don't lose sight of expectation here: Missouri had a lot of variance in their scores but that was because they averaged 42 points a game. Michigan had far less but they were averaging 20.

Offenses that do this quickly are actually more predictable because they get in more trials. Moving fast without sacrificing expectation is advantageous to the better team, which is why Oklahoma was in zero even halfway close games against the Big 12 rabble. (Texas is not rabble, obviously.)

Defenses reduce variance by, you know, having safeties that can tackle. The very best defenses are low variance because all of the outcomes have the same result for the opposition: shame and humiliation. In that situation, punting your ass off makes sense, because you're a big favorite, you're not giving the opponent much of an opportunity and you're reducing variance in a way that helps your overall chances of winning. The main problem with Michigan's defense over the last few years has been their suckiness, which by the way increases variance as your defense falls to a point where opponents can drive the field on them regularly.

I always go back here to the end of the 2005 Ohio State game: Michigan has a two point lead and drives down to the Ohio State 40. Facing third and ten, they run a wide receiver screen for six yards, and then punt on fourth and four from the 34, gaining 15 yards. Ohio State promptly drives the field for the winning touchdown. This came after a Henne-demanded fourth-and-short conversion on Michigan's 40 that led to an apparently-clinching field goal, and was interpreted by yrs truly as a panicked reversion to base instincts from another time.

*(The variance of something that's always zero is zero and it's not much higher for something that's almost always zero. As offenses move towards 50/50 efficiency the variance increases, but in a world like the 54-51 game against Northwestern the variance is low because everyone's always scoring touchdowns. An even distribution of probabilities is always more unpredictable than a set where most of the events are drawn to one or two outcomes.)

Comments