wonkery

[Ed: This week's Mathlete column expands on fourth down decision-making. I haven't seen a graph anywhere near as clear as those included below about how shifting the parameters of the offenses and defenses in question makes major impact on what a correct decision is. This is not a situation where you can just read the decision off a chart. Feel and personal preference will always play a role. It's a complex decision.]

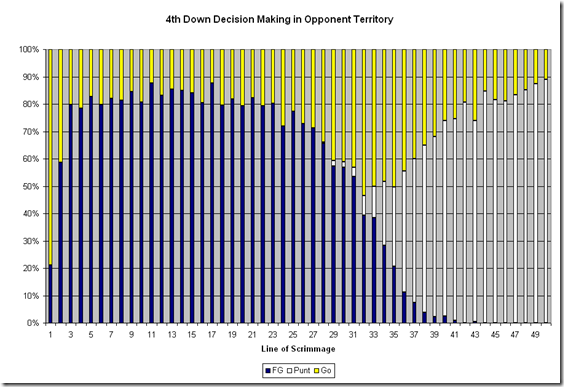

Last week I wrote on the value of special teams but a very interesting side topic arose: fourth down decision making. It started with this chart:

About which I remarked:

The going for it actually peaks between 30 and 35 as more coaches don’t really know what to do so they just go for it.

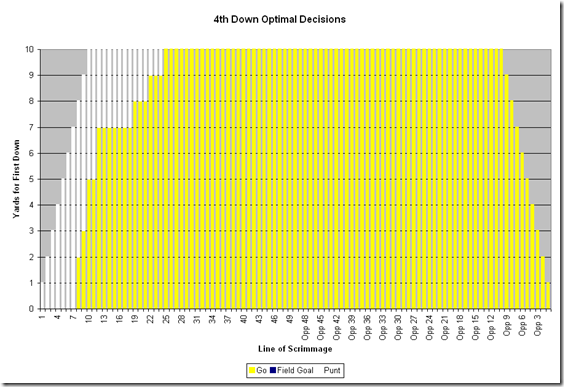

So I decided to look and see what the decision chart should look like on an expected points basis.

Anything close to two different colors is a virtual toss-up. Any gains near a color transition are negligible and not worth noting, but there are very real gains to be made in the heart of the yellow section, where coaches are taking their offenses off of the field far too quickly.

A couple of quick rules of thumb:

- Don’t punt on the opponent’s side of the field.

- Really consider going for it on 4th down after crossing your own 40.

- Field goals only make sense if there are more than 5 yards to go and you are between the 10 and 30 yard lines. If you’re in opponent territory and these two criteria aren’t true, you should be going for it.

I know this is not the first time a topic like this has been presented, David Romer was mostly criticized for his paper on the topic a couple years back (thanks for the reminder Colin). [Ed: Not around here.] Of course there was the great Patriot debate last season when the Patriots elected to go for it on 4th and 2 with the lead in their own territory. Even though the majority of the arguments against this work amount to "people like David Romer and The Mathlete don’t know anything about football and just live in their parent’s basement" I did want to look at the main objections and see if they had any validity.

Objection 1: Does not account for “quick change” momentum

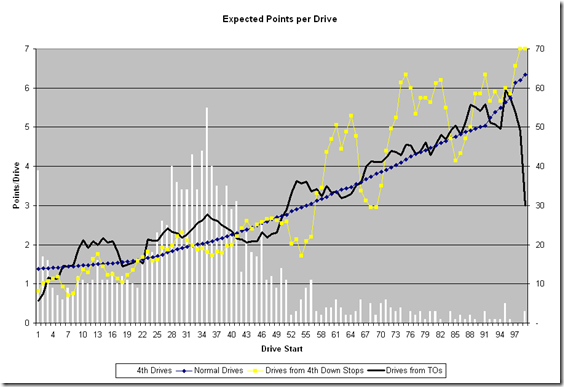

Below you’ll see a chart of the expected points on a drive based on field position, and how teams have actually fared. I also included drives obtained by turnover as comparison to the other “quick change” drive source.

There could be a case that drives started on a short field due to a 4th down stop generate more points than normal drives, but the small sample size reduces how strongly that argument can be made. From 2007-2009, the total points accounted for on drives obtained by 4th down stops (2523) is less than the projected points would be for any drives starting at the same field position (2580). This difference is meaningless statistically, something very damaging to the idea "momentum" helps the opposing offense after their defense gets a fourth down stop.

Adding in the turnovers does nothing to build a case for momentum after big defensive stops or turnovers. The turnover-started drive line tightly hugs the average line. As a whole, the turnover expected points line is slightly higher than the average line, but only by enough to generate an extra touchdown every 50 drives. That's about one every two years or so.

Although it can often feel like there is a big momentum swing after a big stop or turnover, there is scant evidence that it is more than our memories selecting the most traumatic or exhilarating scenes to hold onto. [Ed: for an example of this human tendency to ascribe meaning to unusual events where there is none, see any of the zillion "hot hand" studies.]

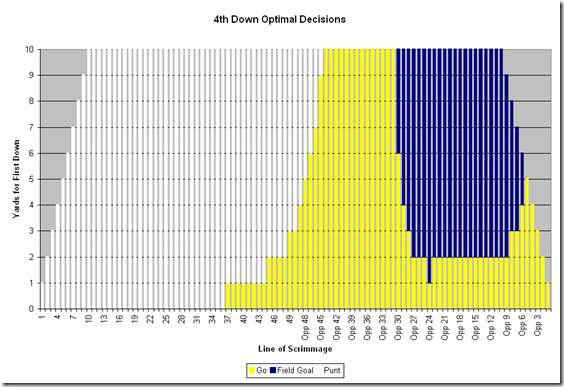

Objection 2: It assumes all offenses and defenses are average

To get a gauge on what “good” can mean in comparison to average, I plotted the best offense and best defense of the last three years against the average team’s expected points per drive.

As a rough approximation, the best offense is about a 1 point per drive better than average and the best defense makes offenses about a point worse per drive.

Scenario 1: Good offense

If your offense is as good as Florida, you should never punt against an average defense. Maybe if you are deep in your own territory, but only in the most extreme situations. This assumes that a new first down gives the Florida offense an extra point over an average team in expected value and a 10 percentage point increase in the likelihood that they convert.

A punt is conceding any chance of scoring and an offense this good should not give up that right so easily. This is the basic philosophy behind the vaunted no punting HS coach in Arkansas. His team isn’t necessary good because he doesn’t punt. He doesn’t punt because his offense is good. Why waste another scoring opportunity?

Scenario 2: Going against a good defense

Playing against a good defense changes the dynamic extensively but it does not mean forgoing the fourth down attempt altogether. With a reduced likelihood of success on 4th down and a reduced payout if the conversion is successful, the 4th down attempt still is an optimal strategy more than is currently utilized. Even against a top national defense, you should still not punt in opponent territory. The field goal becomes a more viable option against the stronger defense and punting becomes a much better idea all the way out to midfield.

[Ed: I think this is moving towards correct strategy since it takes a caveman or a seriously long-yardage situation for someone to punt from inside the opponent's 40 these days. That range from midfield to the opponent 40 is a spot we might see move towards fourth-down aggression in the next few years.

Also note that coventional current strategy gets way less wrong once you ramp up the ability of the defense. If we jacked it up even farther, it might get to the point where punting from the 36 (or even on third down) is a good idea. The flaws in strategy here are leftovers from an era when punting was actually the best option. Thinking has not kept pace with scoring since.]

Scenarios 3/4: Good defense or opponent good offense

The conventional wisdom is that if you trust your defense, you don’t go for it on fourth down. [Ed: In my experience the conventional wisdom is remarkably malleable on this point. If you have a good D and the announcer agrees with the call, the good D will be cited as a reason why.] In reality, the strength of your own defense (or the strength of the opposing offense) is largely irrelevant to the decision. Fourth down decisions are all about offensive opportunity. A 4th down decision to punt is the decision to take the ball out of your offense’s hand, leaving the relative impacts on your defense to negate each other. A 4th down failure puts your defense in a worse situation, but it doesn’t guarantee points for the other team; a good defense is still a major asset in stopping or limiting the other team with good field position. A punt doesn’t guarantee that the other team is going to be stopped, but a good defense makes it more likely. In the end, it’s still all about the offense.

Objection 3: Does not account for game specific situations

This objection does ring true, but its application is much narrower than most people believe. The main flaw with the expected points model is that for most of the game all points are largely equal but at the end of the game, a field goal or even time can become crucially important. If a field goal can tie a game, take the lead, or move said lead from one possession to two (or vice-versa), the decision-making process suggested above can shift radically. This could mean punting near midfield to prevent a short field goal drive for the other team or taking a field goal instead going for it on fourth in field goal range.

These situations are rare, however, and only come into effect in the fourth quarter. When there are likely to be even 2-3 additional possessions, the expected points model still holds up.

Another potential game situation not accounted for above is the presence of a high quality field goal kicker. A very accurate field goal kicker will move the blue field goal “bubble” in the above charts down, making fields more practical in short yardage situations. An above average kicker from long range will move the bubble left. Even a great kicker won’t make kicking inside the 5 practical in very many situations.

Conclusion: In Which Romer Is Re-Iterated

Teams need to be using kickers and punters less and their offenses more. Especially teams with good offenses. If you have a good offense, bringing out the punter should only be done in long distance situations or when deep in your own territory. Scoring touchdowns is the valuable thing in football and giving away a quarter of your plays to kick on fourth down greatly reduces your ability to score them, the gain in field position from a punt is worth less than it is currently perceived to be and the idea that momentum is obtained from a quick change of possession is to be slight at best and most likely non-existent.

One final thought I haven’t been able to quantify yet: if you switch to a fourth down mindset, what opportunities does it open up in play calling during the first three downs of a series. Planning on four plays for a first down instead of three would surely have some value for an offense to adjust and re-optimize their play calling, and the total offensive value could become even greater.

Note: apparently Brian Burke at Advanced NFL Stats and I have been having some of the same offseason thoughts as he just put up another piece on 4th down decision making, and this after we both introduced similar defensive player evaluation metrics within a month of each other.

[Ed: Excellent diary that helps orient everyone to the 3-3-5.]

One of the greatest difficulties Michigan faces in the Big Ten is that there are a vast array of offenses deployed. You have the Wisconsin’s and Michigan State’s of the world still running two TE with a FB and slamming down your throats, and Northwestern and Purdue on the opposite end of the spectrum. Then you have all those teams in between, the single back look from Iowa, the mixed attack of Penn State, and the offense that periodically exists in Columbus and Champaign. Because it is unfeasible to switch defenses to match offenses in college football (see move to 3-3-5 against Purdue in 2008), it is important to find a base defense that can be implemented to at least some degree of success against these different teams. >

This means two things, one, you need some versatility in your players. Two, you need to put your players in the situation that helps them the most. I’m not going to say either way that the 3-3-5 is that, I just want to give a brief overview of the defense and then make a few points at the end.

First I’ll cover some basics.

This is the numbering system I’ll be using, where the dark circle with the X is the center:

Note, that for linebackers, the numbering system adds a zero to the end. For example, if a LB is lined up off the line, but stacked above a 4-tech DE, he would be playing a 40 technique. Pictured below is the base formation.

Defensive ends (DE) are in 4-techniques, or head on with the offensive tackle. Nose tackle (NT) is on the nose of the ball. Outside Linebackers (OLB) are in a 40-tech, while the middle linebacker (MLB/Mike) is in a 10-tech. The strong safeties (SS/Spur) are three yards off the line and three yards outside of the last man on the line. Corners (CB) are 5-9 yards off the line over the wide receivers, and the free safety (FS) is deep center. While this seems like a 2-gap system for the NT, it will be typical to apply some sort of slant to make it actually more of a 1-gap system.

Next you will see a basic coverage that will be run. This is a cover-3, zone under. Notice that there are no stunts or blitzes here. This is a very vanilla defense and would only be run in obvious pass downs most likely. Red is deep zones (in this case thirds), yellow indicates flats/seems, and green is underneath zones for hooks and curls (the MLB in this case covers the “hole”).

The next look is at a very simple outside linebacker blitz. This is still a cover-3, zone under. [Ed: continued after the jump, with lots more diagrams and some simple bullets on pros and cons.]

41