slanty the gecko

[Bryan Fuller]

You're going to have to bear with me on the offensive UFRs this year. The last time I saw a traditional gap-blocked, regular-ol-QB offense for anything more than a one-game debacle was ten years ago. That was the first year I did UFR and most running plays of that sort were deemed "another wad of bodies" because I didn't know what I was looking at. Since then:

- Two years of Debord running almost nothing but outside zone

- Three years of Rodriguez running inside and outside zone with a little power frippery

- Two years of Hoke trying to shoehorn Denard Robinson into a pro-style offense, giving up, and running a low-rent spread offense

- Al Borges's Cheesecake Factory offense that ran everything terribly

- Doug Nussmeier's inside zone-based offense.

I've seen plenty of power plays. Most of them were constraints that could be run simply and still succeed because the offense's backbone was something else. The rest were so miserably executed that they offered no knowledge about what power is actually supposed to look like. I watched a bunch of Stanford but not in the kind of detail I get down to with the UFRs.

![fbz3gg1_thumb[1]](https://mgoblog.com/sites/mgoblog.com/files/images/655ca1995608_CE7E/fbz3gg1_thumb1.png) One thing that I am pretty sure I think is that the popular conception of power as a decision-free zone in which moving guys off the ball gets you yards is incomplete. Defenses will show you a front pre-snap. You will make blocking decisions based on that front. Then the defense will blitz and slant to foul your decisions and remove the gap you want to hit. If you do not adjust to what is happening in front of you then you run into bodies and everyone is sad.

One thing that I am pretty sure I think is that the popular conception of power as a decision-free zone in which moving guys off the ball gets you yards is incomplete. Defenses will show you a front pre-snap. You will make blocking decisions based on that front. Then the defense will blitz and slant to foul your decisions and remove the gap you want to hit. If you do not adjust to what is happening in front of you then you run into bodies and everyone is sad.

What Stanford was great at was running power that was executed so consistently well that it was largely impervious to all the games defenses played. This requires linemen who are downblocking to think on their feet, maintain their balance, and stay attached to guys who may be going in directions they were not expected to. It requires everyone off the line of scrimmage (tailback, fullback, pulling G) to see what's in front of them and adjust accordingly.

Michigan did a bad job of this against Utah. They also got blown backwards too much, complicating decisions for the backfield. The latter was not a problem against a much weaker Oregon State outfit. The former was much better, and that's the most encouraging thing to take from this game.

Here's an example. It's a six yard run in the first quarter on which Oregon State sends a blitz that Michigan recognizes and thwarts. There's no puller on this play; I think it was intended to be a weakside iso that ends up looking not very much like iso because Michigan adjusts post-snap.

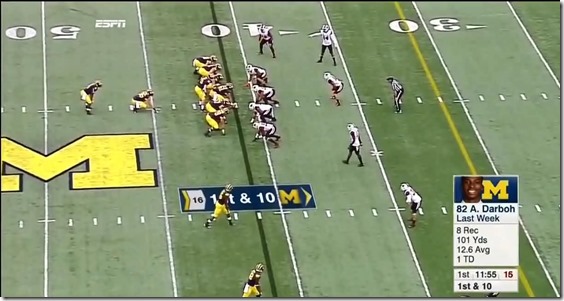

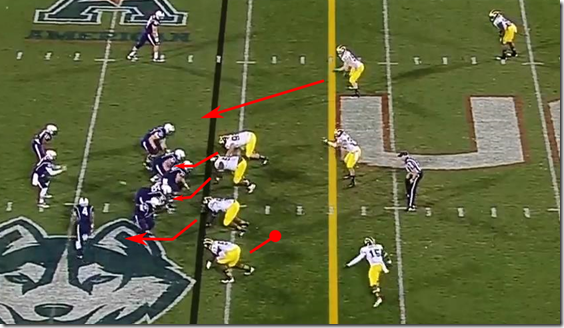

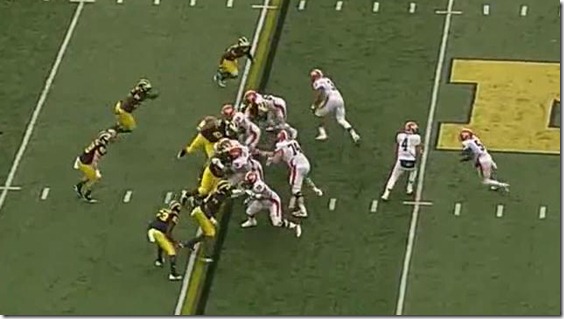

M comes out in an I-Form twins formation; Oregon state is in a 4-3 that shifts away from the run strength of Michigan's formation. They are also walking a DB to the line of scrimmage:

By the time Michigan snaps the ball this DB is hanging out in a zone with no eligible receiver while both WRs get guys who look to be in man coverage. This is not disguised well unless the highlighted player is Jabrill Peppers and can teleport places after the snap:

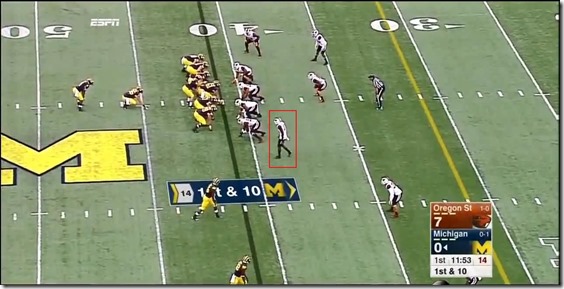

He's going to blitz and the DL is going to slant to the run strength of the line. Michigan will pick this up, and I wonder if they IDed the likelihood of this pre-snap. No way to tell, obviously.

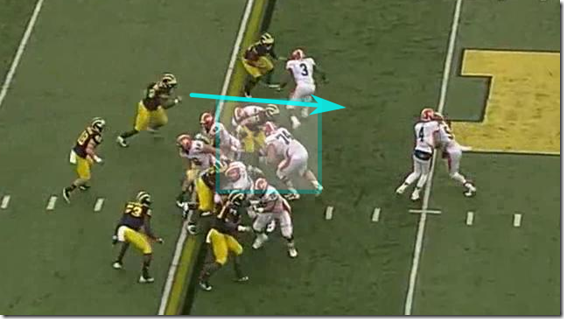

On the snap both the FB and RB start to the weak side of the formation; you can see Erik Magnuson start to set up as if he is going to execute a kickout block on the defensive end:

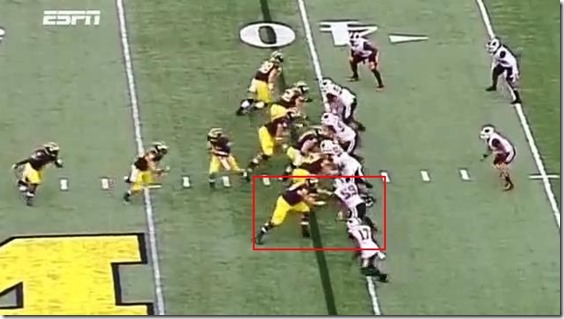

With the blitz and slant from the Oregon DL that's not going to happen. Each Oregon State DL has popped into a gap. Kerridge is taking a flight path to the gap that would normally open between Magnuson and Kalis, the right guard, on a play without this blitz. Without the blitz the DE would be the force player tasked with keeping the play inside of him; Magnuson would have a relatively easy job as he and the DE mutually agreed on where he should go.

Here the DE threatens the play's intended gap. Magnuson can't do anything about that. The D mostly gets to choose what gap they go in, and it's up to the offense to roll with the punches.

Michigan does this:

A moment later Magnuson has changed his tack from attempted kickout to an attempt to laterally displace the DE using his own momentum. Kerridge has abandoned the idea of hitting the weakside B gap and is flaring out for the blitzer.

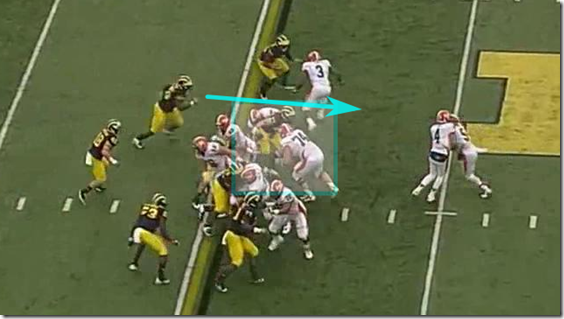

Thunk:

Now, this could be successful for Oregon State still. The slant got five Michigan OL to block four guys. Nobody got downfield; the slant got a 2 for 1. But their MLB has stood stock still for much of this play, and Magnuson ends up shoving his dude past the hash mark—+1, sir. This is a ton of space to shut down, and De'Veon Smith is the kind of back that can plow through you for YAC.

Smith fends off the linebacker with a stiffarm and starts gaining yardage outside; it could be a good deal more but Chesson misses a cut* and the DB forces it back, creating a big ol' pile:

Second and four sounds a lot better than second and eleven.

*[Drake Harris will later pick up a 15-yard penalty for a similar, but more successful cut block; the genesis of that flag is probably Gary Andersen doing some screaming at the official after this play.]

Video

Slow:

Items of interest

You don't get to pick the gap even if it's gap blocking. Defenses slant constantly, and often in a specific effort to foul the intended hole and pop the back out into a place where an unblocked guy can hit. Post-snap adaptation is a must for a well-oiled power running game.

Slants win if they suck away an extra blocker. I would be peeved at the MLB if I was Oregon State UFR guy. While Michigan adapts to the slant well enough to provide a crease for Smith, the blitz means Michigan had to spend a blocker on the defensive back and the MLB is a free hitter. He should be moving to this more quickly than he does.

Slants also tend to open up giant running gaps. Adjustments like the above will often lead to a defender running in one direction suddenly getting unwanted help from an OL. If the OL can redirect and latch on just about everyone is going for a ride here. Once Magnuson locks on and Kerridge targets the DB these are two blocks that are easy to win and Smith is going to have a truck lane.

Given how much space Smith has even a linebacker playing this aggressively who shows up in the gap might lose or get his tackle run through; Michigan's getting yards here, whether it's three or six or more if Chesson gets a good block.

In the past this site has seen arguments about whether meeting an unblocked safety at or near the line of scrimmage is a win for the offense or the defense. I have largely come down on the side of "that absolutely sucks," but when the hole is so big that the defender is attempting to make an open-field tackle it's a lot more appealing.

Michigan WRs need to be more careful with the cut blocks. You can cut a guy from the "front," by which the NCAA means the area from 10 to 2 on a clock. (Seriously, that's the way it's defined in the rulebook.) This was very close to a flag, and Michigan got one later.

I wish Michigan was running pop passes, as those are good ways to get defensive backs hesitant about running hard after plays like this. Maybe in a bit.

![fbz3gg1_thumb[1] fbz3gg1_thumb[1]](https://mgoblog.com/sites/mgoblog.com/files/images/655ca1995608_CE7E/fbz3gg1_thumb1.png) This space mentions all the time that in Mattison's defense the usual end/tackle distinction for the four guys on the defensive line is not a good representation of how similar or interchangeable those guys are. The nose stands alone; the SDE and 3TECH are kind of the same player, and the WDE and SAM are kind of the same player.

This space mentions all the time that in Mattison's defense the usual end/tackle distinction for the four guys on the defensive line is not a good representation of how similar or interchangeable those guys are. The nose stands alone; the SDE and 3TECH are kind of the same player, and the WDE and SAM are kind of the same player.

A primary reason for this is that Michigan runs a ton of defensive plays on which the SDE/3T and WDE/SAM switch roles. These are so common that they have a mascot around these parts: Slanty The Gecko, who was inexplicably the first Google hit for "line slant football" a ways back. This is another Slanty post.

I've covered this ground before, but to reiterate: a slant is an aggressive defense designed to get penetration as offensive linemen are surprised by the gap the defender tries to fill. This can lead to unblocked defenders—and big cutback lanes. Unless the offensive line makes the on-the-fly adjustment they lose a blocking angle at best, and then you've got a free hitter… as long as your linebackers understand what's going on in front of them and present themselves at the spot they should.

I'm revisiting this because the UConn game provided a look at what happens to the WDE when the playcall asks him to become the SAM. Both of these plays are Frank Clark-centric; as is often the case, this means one is good, one is bad.

The Good Part

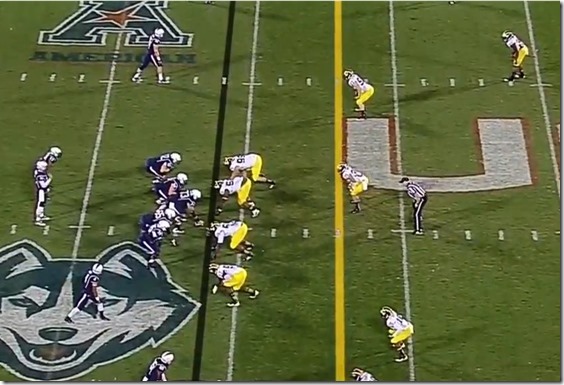

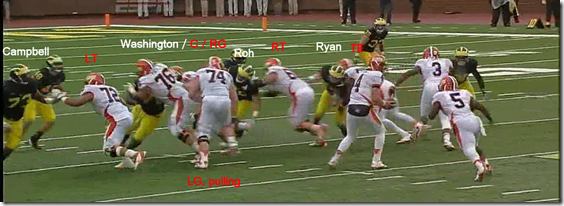

First quarter, second and four on the UConn 29. they come out in four-wide. Michigan shows five in the box with linebackers over the slots.

That safety is a bit of a giveaway that Michigan will bring Beyer off the edge.

On the snap, Michigan does send Beyer; simultaneously UConn sends a slot guy in motion, threatening a jet sweep.

One of the primary goals with a slant is to confuse an offensive lineman expecting one assignment executing that either against air or a guy who he really can't block. Here that's going to be the right tackle. Henry, our last arrow to the bottom of the screen, is going to head outside immediately on the right guard; he needs to get upfield and be the force player.

Clark will "fold" back after taking a step past the line of scrimmage to get the right tackle to commit.

[After THE JUMP: it's like origami except someone gets buried at the end.]

![fbz3gg[1] fbz3gg[1]](https://mgoblog.com/sites/mgoblog.com/files/fbz3gg1_thumb.png) wsg Slanty, the football-playing, jean-vested gecko who is inexplicably the first hit in Google images for "line slant football", or at least was a year ago.

wsg Slanty, the football-playing, jean-vested gecko who is inexplicably the first hit in Google images for "line slant football", or at least was a year ago.

One of my main concerns going into the season was what would happen to the short-yardage defense that Michigan was so good in a year ago without Mike Martin and RVB. Turning a third and short into a punt is 50% of a turnover, and Michigan could paper over a lot of deficiencies last year by telling Mike Martin to destroy some guys on third and one, thus allowing other guys to tackle.

Illinois disclaimers are in full effect—they can't do anything against anyone—but the Illini could do even less of anything against Michigan Saturday, and getting bombed on short yardage was a major part of that.

Michigan blew up Illinois short yardage with slants. Multiple times we saw this pattern:

- Michigan slants away from a power run.

- The playside end gets inside and upfield of the tackle or end trying to block down on him.

- The pulling guard bangs into the playside end.

- Linebackers profit.

Actually, Michigan doesn't so much "slant away" as show one defense and run another. When Michigan isn't running their base 4-3 under call they are inverting it by blitzing Ryan and moving everyone else over a gap.

Let's see it in action. /fishduck'd

It's fourth and one on the second and final Illini drive to make it past midfield, just before the half. Michigan has just stoned a power run by Riley O'Toole for a half yard to set up this opportunity. Illinois comes out in one of their standard sets, a pistol with two tight ends to one side of the line and twinned WRs.

Michigan is in an over this time since the strength is to the boundary, but Illinois will move a tight end over and not have an unbalanced strength on the line on the snap anyway so whatever.

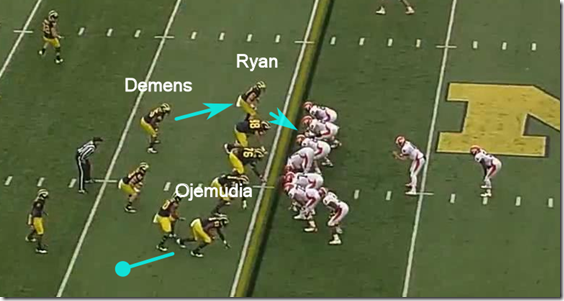

This is what Michigan does:

They're essentially moving everyone over a a gap and dropping Ojemudia into a short zone. On run plays he "folds" which consists of backing off, keep an eye out for cutbacks, and allowing the linebackers to run to the frontside. If you're watching a replay and are wondering if Michigan's doing this gap-shift thing, the WDE backing off the LOS is a sure tip. If you watch for it, you will find it—Michigan runs this on upwards of 20% of downs.

On the snap, Ojemudia backs off and the line shoots down. Gordon, who is right behind Ojemudia in the above frame, has followed the TE across the field and now takes contain responsibility to the playside.

You can see the slant better from this angle:

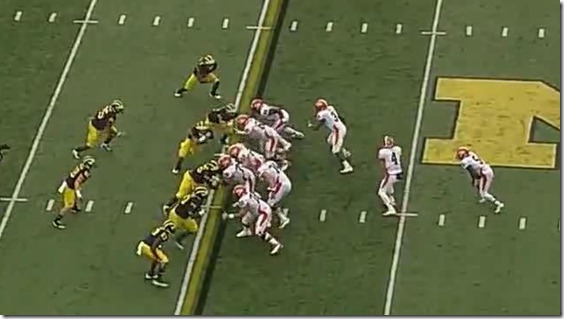

Campbell is now attacking outside the left tackle, like he's a WDE. Roh and Ryan both shoot gaps to the inside. They get penetration, giving up an outside crease to do so.

Ryan gets under fast. He's essentially through clean, so the pulling G has no choice but to pick him off. Demens is already a yard off the LOS and charging as the handoff is made.

Now it's all about tackling.

Check.

Demens went inside out here as the back tried to go north and south on fourth and inches. That allows him to use the pile as help, and look at Desmond Morgan popping up to say hi/clean up any messes.

If you take a second look at this frame:

Note how Morgan is also clean and has stepped playside as the slant develops. He's still trying to check for any potential cutbacks and find the gap he's going to fill; he is available if the back makes Demens miss or threatens to power to the line.

Video

[After THE JUMP: play it sort of again, Sam.]

63