scrape exchange

Michigan's quarterback-centric running game has been a shell of itself this year. Our understanding is Shea injured his oblique on the first play from scrimmage against MTSU, and has since been loathe to keep the ball on reads. Since Michigan spent all offseason transitioning to an extremely read offense, this was a bad development.

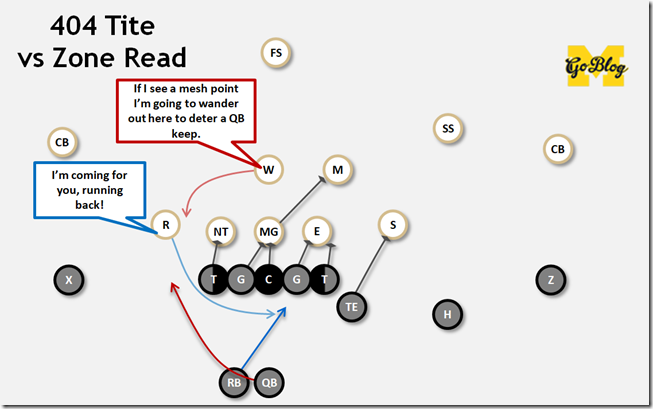

I wrote a few weeks back how Army used this to their advantage by having the backside LB option the backside, flying outside when he read a mesh point to force a keep read against a crashing DE and slanting DL.

Shea compounded the issue by letting the backside LB off the hook when he didn't fly far enough outside. With Patterson not able to keep, Michigan shelved the zone read stuff, ably demonstrating (as much as the awful camera angle allows anyways) why a zone read is important if you're going to leave a guy unblocked:

That brings us to this week, when the flerp doodly poop experts themselves came to Ann Arbor. For most of the afternoon, Michigan ran from the shotgun without bothering to read anybody while Rutgers Rutgered. When you run from the shotgun without a zone read you don't get much—there's a lot of ground to cover from a stopped position after the handoff. As such Michigan's ground game met safeties after three yards and ground out another two because Rutgers for most of the day. In other words, we got to see just about zero of Michigan's real offense as long as the starters were in.

But Shea wasn't the only quarterback who played Saturday. Up 38-0 with 1:32 remaining, Michigan put in Joe Milton, and flipped the quarterback keeps back to the On position. It was our first chance since literally the season's first snap to see what the Gattis offense is trying to do. And it was actually kind of interesting. Wanna see?

[After THE JUMP: R-E-S-P-E-C-T, s-o-r-t-a]

Last week in this column I talked about how the changes to Michigan's running game under Gattis seemed to be mostly about adding a read to it. One week later, at least among fans who know the first damn thing about Army, we're all grumbling about about how Michigan reversed the gains of their Gattisization by dorfing the reads.

To be sure, there were plenty of plays where Shea (and one where McCaffrey) had a keep read and handed the ball off. It's also pretty evident—despite what Harbaugh said in the presser—that Patterson was playing hurt. Also later in the game Army knew Michigan wanted to avoid passing and started bringing their cornerbacks on blitzes off the edge.

However, on re-watch, I noticed a lot of other plays where the DE crashed but Army was really taking away both options with what's called a "Scrape Exchange." Maybe showing these plays, what Army was doing, and what Michigan could have done in response, will ease some of the whinging?

----------------------------------------

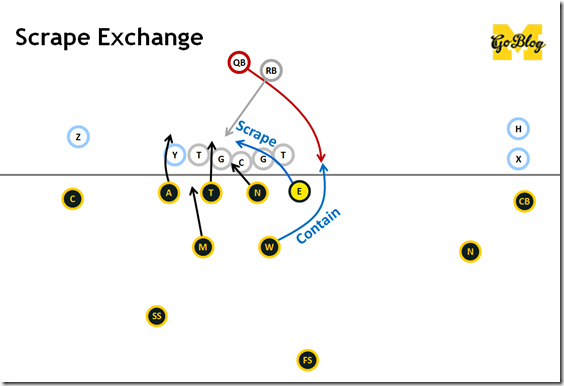

1. What's a Scrape Exchange?

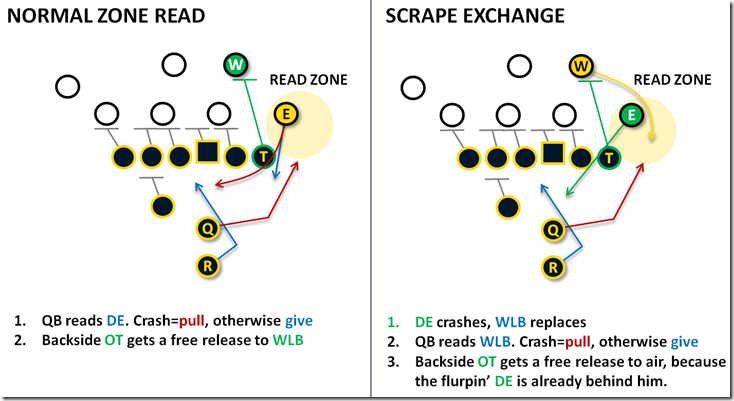

It's a defensive "paper" call to the "rock" of the zone-read option play. Essentially they're flipping the jobs of the two backside guys, having the DE crash inside while an LB loops into the spot the DE formerly occupied.

The win for the defense is the green (i.e. the B gap) block in this diagram. The offensive play is designed to get that block accomplished with a tackle releasing on a linebacker. By exchanging jobs, the defense wins the block and can force a read right into it.

I covered this a few years back when we were meeting Don Brown, and again when Iowa adapted to Michigan's Pepcat package (and Microsoft still included their full video editor with Windows). Unfortunately something on our site is breaking the links to old images at the moment, but you can probably get the gist just from the video with the Bear vs. Shark song on it.

[After THE JUMP: We have the technology, but do we trust it?.]

[This series is a work-in-progress glossary of football concepts we tend to talk about in Upon Further Review and Neck Sharpies, etc. Previously:

Offensive concepts: Run-pass options (RPOs), High-Low passing routes, Covered (ineligible) receivers/tight ends, Blocking: Reach Blocks, Kickout Blocks, Wham Blocks

Defensive concepts: Keeping Contain/Lane Integrity, Force Player, Hybrid Space Player, One-Gap Fronts, Coverages: Tampa 2, Pattern-Matching, Quarters and how MSU runs it

Special Teams: Spread punt vs NFL-style]

------------------------------------------

In the Iowa UFR Brian talked about how opponents had solved Michigan’s Peppers-as-Option-QB (we were calling it the “Pepcat”) package with an old fashioned zone read beater: the scrape exchange. Brian on the above:

Peppers is reading the DE and pulls; Iowa inserts a linebacker directly into his path since that DE is covering up the inside gaps the LB would usually be tasked with.

Since I watched the Rodriguez era at Michigan this is familiar to me. Also familiar to me: the various counter-punches Michigan threw at this. Remember that brief era when Carlos Brown and Brandon Minor were running directly off tackle for big chunks on the regular? That was due to Michigan's response to this kind of approach: blast that guy slanting even further inside, kick the linebacker out, and thunder directly to the secondary.

Since that was buried in a UFR I figured we might discuss scrape exchanges in some more detail here.

What’s a scrape exchange: It’s a defensive concept that flips the roles of two backside defenders, thus covering both sides of a quarterback’s zone read. The guy the offense thinks it’s optioning, usually a defensive end, “crashes” (move horizontally across the line of scrimmage) and is “exchanged” for another defender, usually a linebacker, who “scrapes” to the area the end vacated.

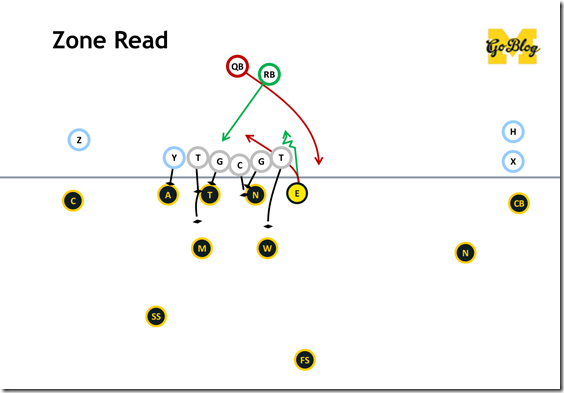

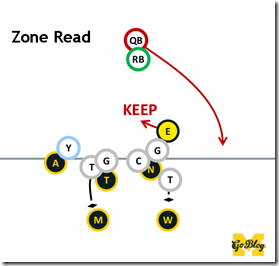

What’s it for? It’s the paper to the zone read’s rock. So you remember zone read:

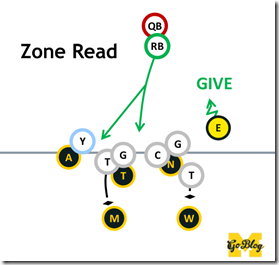

This is the play that Rich Rodriguez invented to dawn the spread era. The offense leaves the backside defensive player unblocked and the quarterback options that guy. If the player (usually a defensive end) takes the opportunity of no blocker to scrape across to the running back’s path, the quarterback keeps it and runs into all the space left behind. If the optioned defender forms up to keep the quarterback contained, the running back gets the ball with the benefit of that extra blocker.

After decades there are lots of variations, but this is the gist of that offense. A scrape exchange makes the quarterback keep it, and makes that decision also wrong:

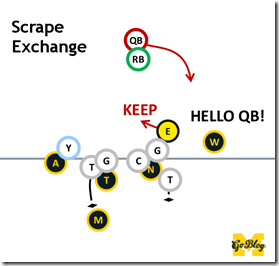

The quarterback running a zone read will see the defensive end crashing and keep the ball, only to find the linebacker appearing where the quarterback was about to run it. What the QB is expecting is on the left below; the result of the scrape exchange is on the right:

[After the JUMP: see it in action, and ways to beat it]

40