pulling linemen

What is the difference between this run:

…and this run:

?

If you guessed "the one Harbaugh/Drevno were coaching got yards and the one from Hoke/Borges didn't" you win a running theme of the 2015 offseason. The results are certainly stark; why that's true is what we're interested in.

The Power Play

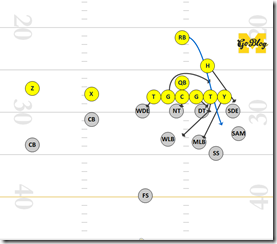

These are both the same play by the offense, and the same play Brady Hoke promised to make into Michigan's base because it is the manliest of plays. It is Power-O, the one where you pull the backside guard and try to run between the tackles.

You can click for biggers

The play is relatively simple to draw up and complex to execute because it uses a lot of the things zone blocking does, including having the blocking and back react to what the defense does. For all the "manball" talk this isn't ISO, where you slam into each other quickly. Depending on how the coach wants to play it and what defensive alignment you see, the basic gist is to get a double or scoop of the playside DT and kick out the playside DE, then have an avalanche of bodies pour into that hole—if the defense is leaping into that gap you adjust by trying a different hole further outside. Leaving two blockers to seal off the backside, one blocker, usually the backside guard, pulls and becomes the lead blocker—it's up to him to adjust to what he sees when he arrives.

You can run this out of different formations with different personnel, and the one immediately apparent difference in the above diagrams is Michigan was more spread—a flanker (Z) is out on the opposite numbers and the strongside is to the boundary; after the motion this is an "Ace Twins". Stanford ran this with a heavy "22-I" formation, meaning two backs (RB and FB) and two tight ends (Y and H) in an I-form. The benefit Michigan gets from its formation is the guy Stanford would have to block with its fullback Michigan has removed from the play entirely by forcing him to cover the opposite sideline.

What Stanford gets in return for its fullback is matchup problems: the open side of the field is going to be two tight ends and a fullback versus two safeties and a cornerback. Run or pass that can go badly for the defense as these size mismatches turn into lithe safeties eating low-centered fullbacks, and dainty corners on manbeast TEs.

In War of 1812 terms, Michigan is the Americans, sending the fast-sailing frigate Essex in the Pacific so the enemy has to move ships to the Galapagos instead of harassing the Carolinas. Stanford is the British, parking 74-guns ships of the line where engaging them cannot be avoided and trusting the outcome of any forced engagement should turn in their favor. The point is both work to the advantages and disadvantages of the talent on hand. (In this analogy Borges is a guy trying to use Horatio Nelson tactics with a Navy of sloops and brigs).

That being said, it still works as well as anything—people did in fact score points before the spread, and those who scored a lot of them could do so by keeping defenses off balance and with good execution. As we'll see both of those factors played a big role.

[after the jump]

Brian,

As you've referenced with KenPom's research several times, it would appear that the best way to defend the 3 point shot is to keep your opponent from shooting them at all. Unfortunately, according to an ESPN insider article, Michigan is allowing its opponents to shoot them on 36.9% of their possessions, which ranks 295th in the nation. Does this concern you? I think we would all hate to see Michigan beaten in the tournament by a less talented opponent with a hot hand from deep because they can't prevent teams from getting off 3 pointers.

Thanks.

Somewhat. The nice thing about Michigan's defense is how few shots at the rim they give up. Michigan's forcing more two-point jumpers than any team in the league except Nebraska:

Team Defensive Summary

| Shot Type | % of shots | FG% | % of Shots Blocked | Unblocked FG% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At Rim | 25% | 62% | 10% | 69% |

| 2pt Jumpers | 39% | 35% | 5% | 37% |

| 3pt Shots | 36% | 32% | 1% | 32% |

The conference:

| Team | Rim | 2PT | 3PT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nebraska | 24 | 46 | 30 |

| Michigan | 25 | 39 | 36 |

| Indiana | 26 | 37 | 36 |

| Iowa | 27 | 38 | 34 |

| OSU | 28 | 38 | 34 |

| Minnesota | 29 | 39 | 32 |

| Penn State | 31 | 30 | 40 |

| Purdue | 33 | 41 | 26 |

| Wisconsin | 33 | 42 | 26 |

| Illinois | 34 | 31 | 35 |

| MSU | 35 | 34 | 31 |

| Northwestern | 39 | 30 | 31 |

Insofar as shots are migrating to three-pointers, they're shots at the rim. So… that's okay. Ideally you'd like to see that Nebraska shot configuration, but to do that the Huskers give up on the idea of offensive rebounding and steals.

I'm not sure what Michigan can do to improve their defense at this point. Forcing a lot of jumpers plus their defensive rebounding and lack of fouls has propped their defense up, and that's about all they can do. They don't have a shotblocker—at least right now, maybe Horford can provide some of that later in the season—or an elite perimeter defender. They rotate out on pick and rolls to prevent guys getting to the basket, and then you have to start rotating away from the corners. Threes inevitably result… if you're not Wisconsin.

As for the tourney, it will be tough for any major underdog to keep up with Michigan's offense, but a second or third round matchup against a good defensive team that takes and hits a lot of threes would be worrisome.

Brian,

Whenever Michigan gets a 3-star recruit earlier in the process, there tends to be widespread complaining about taking up scholarships that could be filled by more highly rated players. The general response to that is, "I trust the coaches to evaluate players." This got me to thinking that most major programs essentially have their pick of just about any three star player that they want.

My question is, do three star and lower players who go to major programs perform better on average than the total population of three star players?

I understand it would be hard to distinguish between a three star player taken for depth/filling out a roster purposes compared to a three star player who the coaches think are better than their ranking, but I thought it might be an interesting topic to explore.

I'd guess it's actually worse since there's more competition and recruiting sites give recruits at the bottom end of the scale a courtesy bump to three stars 90% of the time a nobody commits to a power program.

At Purdue, everyone is a three-star player and someone has to be relied upon; sometimes you get Kawann Short. At Michigan—at least at Michigan in the near future—the three star is going to have to climb over some other guys to get on the field.

I do think that there is a big difference between a recruitment like Reon Dawson—who Michigan clearly grabbed to fill a previously designated spot that was vacated—or Da'Mario Jones—seemingly offered once Treadwell flitted off—and Channing Stribling, who Michigan liked at camp and then had a very nice senior year. To put in in Gruden terms, did Michigan want THIS GUY or just A GUY?

Brian,

In your post, "Aging in a Loop", you mentioned how the solid defensive rebounding performance in Columbus proves that we are for real on the boards this year. I agree completely, but it got me wondering how much of that has to do with our sudden ability to actually have three to four non-midgets (relative use of the term, I get it) on the floor at once. I can't remember too many Michigan teams having anything resembling a luxury of length in quite some time.

Have ever looked for or found any statistical correlation between average height and rebounding prowess? Even the least astute observer must realize it will benefit the numbers, but I guess what I'm after is just how much it actually does?

- chewieblue

[Note: since this email came in Minnesota did pound Michigan on the offensive boards.]

While much-improved, Michigan still isn't a very big team. Replacing Novak and Douglass with a couple of 6'6" guys and adding McGary into the mix has pushed them to a hair above average on Kenpom's "effective height,"* but that's in the context of 347 D-I teams. There are entire conferences where the 6'10" guy is a tourist attraction. They remain a lot shorter than Kentucky, Arizona, USC, Miami, Gonzaga, Eastern Michigan, and others. Effectively four inches shorter, in fact.

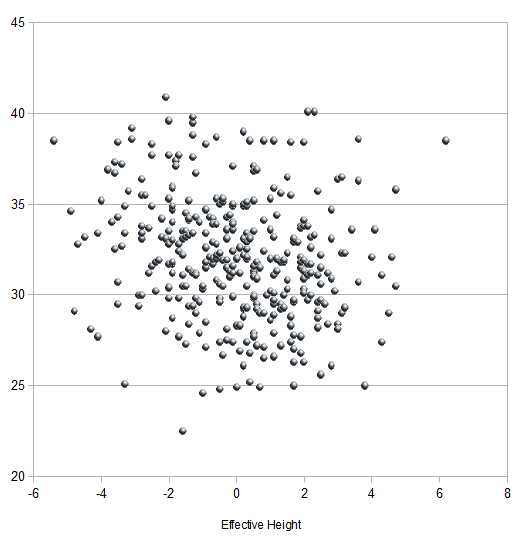

Michigan's moved up in the world in that stat—they've generally hovered around 250th in effective height since Beilein arrived—but I don't think that's the reason they've been so good at rebounding this year. I crammed together the data available on Kenpom to eyeball an ugly scatter plot, and here it is:

Libre Office makes sinfully ugly graphs yo.

That round ball with a dense central cluster is typical of things that are not correlated. You'd find something similar if you graphed hair color versus desire to eat bananas.

There is no correlation between effective height and defensive rebounding. If you insert a trend line into this—something I don't like to do in low-correlation graphs like because it implies that there actually is a trend—it actually goes down as your height goes up, at a surprisingly steep slope. Some people would try to apply some crazy mechanism to make that make sense here; I'm just going to tell you there is no meaning. There does seem to be some correlation between EH and offensive rebounding, but not much of one.

Anecdotally, that enormous Eastern Michigan team Michigan played earlier this year is below average at both facets of rebounding despite having played only a few games against decent competition. They're hideous on the defensive glass.

In general this is good news for Michigan, a team that trades some rebounding muscle for increased offensive effectiveness. But why are they so much better this year than last? Well:

- Luck, always luck.

- Effective height does not capture the difference between Mitch McGary and Evan Smotrycz very well.

- Michigan has not trudged through their Big Ten schedule yet; IIRC they entered conference play last year in the top ten and ended up 9th in conference, dropping to 99th overall.

- Tim Hardaway is serious, man.

- Some teams are abandoning the offensive boards in an effort to choke Michigan's transition game off.

If you asked me to put weights on these things I would give them nearly all equal weight, which means they can expect some regression as #1 and #3 betray them but should realize a significant gain from last year's 9th-place conference finish.

SIDE NOTE: You'll notice that GRIII > Novak is not on that list. While it's true that GRIII is much better on the offensive boards than Novak was, their defensive rebounding is essentially identical, lending credence to the idea that getting on the defensive glass is a matter of effort and positioning while offensive rebounding is more about being a skyscraper-bounding genetic freak. Holla at yo' Petway.

*[IE, if you have a seven-footer who plays 10 minutes and a 6'8" guy who plays 30, the 6'8" guy counts three times more than the seven-footer.]

Pulling: hard?

Brian, Quite often the site discusses the ability of an offensive lineman to pull. Why is this difficult? My understanding is that pulling requires the lineman to:

(0) (set up:) ignore the guys across from him before the snap, because the lineman is about to pull,

(1) after the snap, back up a step or two,

(2) run sideways behind other blockers, and then

(3) find a guy to block.

So what is hard? I'm not saying there isn't anything, I just don't know what it is. Is finding the right guy to block hard? Or backing up and running?

Also, have you thought about doing a basketball version of HTTV?

Best, PR

One of the major takeaways from the clinic swing I did last spring was that everything is hard on the offensive line. I missed most of a three-hour presentation by Darryl Funk on inside zone because I was at Mattison's thing, and when I came in I was too far gone to understand much. I also sat in with a wizened consultant who scribbled various v-shaped diagrams on an ancient projector and demonstrated how if you stepped like so your world would end, and if you stepped like so demons would pour into the world from outside known space, but if you stepped like so there was a slight chance of you living to see dinner.

All of these steps looked identical to me. Offensive line is hard.

So. Consider the pull. You are 300 pounds, and you are lined up across from men who would like to run you over, and you are trying to get to a hole past other 300 pound men before a 200 pound man lined up a gap closer to this hole can get there. On the way you may encounter bulges in the line you have to route around. When you arrive you have to instantly identify the guy to block, reroute your momentum, and get drive on a guy.

This is a tall order. Michigan particularly had difficulty with step 2 the last couple years. Here's a canonical example from the uniformz MSU game. Watch Omameh (second from the bottom):

"Run sideways" goes all wrong there as Omameh arcs slowly and Denard ends up hitting the hole before he does; Denard has to bounce as a result when a block on Bullough is promising as the left side of the line caves in MSU.

To get to the place you are supposed to be you have to execute a series of steps as carefully choreographed as anything on dancing reality TV and be able to adapt on the fly, and you have to be able to redirect your momentum quickly enough to go in three different directions in a short space of time, with enough bulk to be, you know, an offensive lineman. Getting there in time is harder than anything the tailback has to do.

How does this impact Michigan's search for run-game competence in 2013? I hope it doesn't since I'd rather have Schofield back at right tackle than moving back inside.

60