fitzgerald toussaint

A series covering Michigan's 2010s. Previously: TEs, FBs, and OL, best blocks, the aughts.

Methodology: The staff decided these together and split the writeups. Considering individual years but a player can only be nominated once.

QUARTERBACK

DENARD ROBINSON (2010)

one shining moment [Bryan Fuller]

A decade after the 2010 season, Denard Robinson is still the NCAA Football cover guy. This is in part because the NCAA would rather have no money than share some of it with its players, but it also speaks to the hold Robinson had on college football's imagination. Robinson's career started with a near-literal bang and blossomed into a minor national obsession; it ended with Robinson playing running back in the Outback Bowl because his elbow didn't work anymore.

With some exceptions* NCAA Football cover guys were coming off either legendary team successes (Tim Tebow), legendary individual seasons (Charles Woodson), or both. Denard is the only guy on the cover who ended his final season injury-riddled in a bowl that is so barely New Year's Day that Northwestern's played in it. And when it was announced everyone went "obviously."

That's because Robinson was a video game quarterback brought to life. If you don't know what you're doing you pick the team with the fastest quarterback. You might mistake the snap button for the pitch button on the first snap. Might put the ball on the ground. And then it might not matter at all.

That was Robinson in 2009. In 2010 he won the starting job from Tate Forcier, nuked UConn, and then had one of the greatest individual games in Michigan history against Notre Dame: 24/40 passing, 244 yards, 1 TD, 0 INTs, and 258 yards rushing at 9.2 yards a pop. I am pretty sure the happiest I've ever been after a football game was sitting in the Notre Dame Stadium stands longer than I'd ever sat in the stands before:

When the band marched out, we thought that was our cue. I grabbed one of the souvenir mugs as we exited. When I got home I crudely carved "28-24" on it with a steak knife. It's in the closet. Our walk back was half-accompanied by the band. We met a goodly chunk of my family walking the other way, exchanged excited greetings, and then went about the business of getting out of town. We got to the Chili's just as the adrenaline wore off and the stomach reasserted itself.

A few minutes before everyone filed out Denard Robinson zinged a skinny post to Roy Roundtree on third down and finished the job himself. In the first half Robinson had snuck through a crease in the line, found Patrick Omameh turning Manti Te'o into a safety-destroying weapon, and ran directly at me until he ran out of yards.

He knelt down to give thanks, and that felt inverted.

He broke the NCAA record for rushing yards by a quarterback with 1702 yards at 6.6 YPC(!!!) and completed 63% of his passes for 8.8 YPA, 18 TDs and 11 interceptions. He didn't tie his shoes and he smiled all the time. He showed up to basketball games with Roy Roundtree like he was any other student.

standing in the back next to Roy, Kenny Demens, and JB Fitzgerald [Eric Upchurch]

It didn't last—couldn't last. Rich Rodriguez managed to parlay the #2 S&P offense into a mostly deserved firing, Brady Hoke and Al Borges had no idea what to do with him, and Robinson's ulnar nerve started its slow decline. The "what if Rich Rodriguez didn't have the worst defense in Michigan history at the same time he had Denard Robinson" question is the decade's greatest counterfactual.

There are no other real contenders for this spot. The only other Michigan QB to get drafted this decade was Jake Rudock, who went in the sixth round after a one-year grad-transfer cameo. Shea Patterson does not look set to join them. And there's your decade in a nutshell: the best QB season was the first one, and then pro-style ruined everything.

-Brian

*[There was a two year period where EA had a different cover for every platform they made the game for, which led to guys like Utah QB Brian Johnson and WVU fullback Owen Schmitt on the cover. Most ignominiously of all, the 2009 wii version of the game had Sparty on the cover. The mascot. Also one year they put Boise State QB Jared Zabransky on the cover, presumably for the same reason Gameday occasionally visits Colgate or wherever.]

[After THE JUMP: Okay, we're not writing up this much again. Except maybe for the 4th place receiver as payback for not making him 1st string]

What is the difference between this run:

…and this run:

?

If you guessed "the one Harbaugh/Drevno were coaching got yards and the one from Hoke/Borges didn't" you win a running theme of the 2015 offseason. The results are certainly stark; why that's true is what we're interested in.

The Power Play

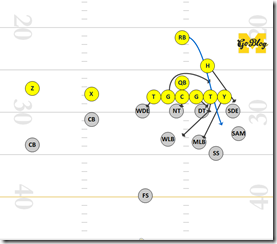

These are both the same play by the offense, and the same play Brady Hoke promised to make into Michigan's base because it is the manliest of plays. It is Power-O, the one where you pull the backside guard and try to run between the tackles.

You can click for biggers

The play is relatively simple to draw up and complex to execute because it uses a lot of the things zone blocking does, including having the blocking and back react to what the defense does. For all the "manball" talk this isn't ISO, where you slam into each other quickly. Depending on how the coach wants to play it and what defensive alignment you see, the basic gist is to get a double or scoop of the playside DT and kick out the playside DE, then have an avalanche of bodies pour into that hole—if the defense is leaping into that gap you adjust by trying a different hole further outside. Leaving two blockers to seal off the backside, one blocker, usually the backside guard, pulls and becomes the lead blocker—it's up to him to adjust to what he sees when he arrives.

You can run this out of different formations with different personnel, and the one immediately apparent difference in the above diagrams is Michigan was more spread—a flanker (Z) is out on the opposite numbers and the strongside is to the boundary; after the motion this is an "Ace Twins". Stanford ran this with a heavy "22-I" formation, meaning two backs (RB and FB) and two tight ends (Y and H) in an I-form. The benefit Michigan gets from its formation is the guy Stanford would have to block with its fullback Michigan has removed from the play entirely by forcing him to cover the opposite sideline.

What Stanford gets in return for its fullback is matchup problems: the open side of the field is going to be two tight ends and a fullback versus two safeties and a cornerback. Run or pass that can go badly for the defense as these size mismatches turn into lithe safeties eating low-centered fullbacks, and dainty corners on manbeast TEs.

In War of 1812 terms, Michigan is the Americans, sending the fast-sailing frigate Essex in the Pacific so the enemy has to move ships to the Galapagos instead of harassing the Carolinas. Stanford is the British, parking 74-guns ships of the line where engaging them cannot be avoided and trusting the outcome of any forced engagement should turn in their favor. The point is both work to the advantages and disadvantages of the talent on hand. (In this analogy Borges is a guy trying to use Horatio Nelson tactics with a Navy of sloops and brigs).

That being said, it still works as well as anything—people did in fact score points before the spread, and those who scored a lot of them could do so by keeping defenses off balance and with good execution. As we'll see both of those factors played a big role.

[after the jump]

![10770781156_6945156a37_z[1] 10770781156_6945156a37_z[1]](https://mgoblog.com/sites/mgoblog.com/files/images/bd670d47d43a_A40C/10770781156_6945156a37_z1.jpg)

Bryan Fuller

Hi Brian,

I don't pretend to know the intricacies of football but during the Nebraska game it seemed that Toussaint, in pass protection, would wait for his blocking assignment to come to him before engaging the player. Seeing as Toussaint is significantly smaller then the LB or lineman he's been assigned to block this usually resulted in Toussaint getting pushed backwards (physics and all). Is this how RBs are typically coached to play pass protection?

Thanks,

Jack C.

I mostly stay away from the how of any particular technique failing; more of a "what" guy since I didn't play the game, etc. But to me Toussaint's blocking issues stem from three problems:

- Michigan's line has to resort to slide protections that often expose him to a pass-rushing DE. This is a bad matchup for anyone.

- He's part of that need to resort to slide protections since his recognition isn't good; when he is tasked with identifying guys to pick up he often catches them. Vincent Smith and Mike Hart would find guys and then get some momentum before making contact.

- He hits guys too high sometimes, which makes it easy for them to shed him and attack. Smith and Hart got low, or in Smith's case existed in a perpetual state of low-ness.

3 is his problem, 2 is part his and part a holistic inability to pick up blitzes, and 1 is not his fault.

What's different about this year?

Greetings –

Regarding the offensive line, I saw some comments that intrigued me that intrigued me the other day and I’m curious your perspective.

Borges indicated that another variable in the mix this year is that it’s “the first year in the scheme we’ve wanted to move to.” Based on your work therefore, do you conclude that:

1) There is a significant difference this year in scheme, protections, and what the offense is asking of the o’line?

2) That experienced lines would be impacted by such a scheme change?

3) That inexperienced players would unimpacted (i.e. just as inexperienced)?

4) That therefore the years experience/games experience would also be negatively impacted from a production standpoint.

So that in conclusion – there’s actually hope bc the ones that are young are young and the ones that are supposed to have experience have less experience than one would otherwise understand to be true.

And – that next year or the year after really will be better!

Keep up the good work.

-Andy

Unfortunately, I'm not seeing a whole lot of evidence for that rationale.

Borges's comments make no sense. This year started out with Michigan running a bunch of stretch plays, which was a departure from what they'd done the first two years… and a staple of the Rodriguez offense. If that's what he meant, he could have just, you know, kept running the stretch.

Instead Michigan was almost exclusively an inside zone and power team their first two years here, and the differences between running those things from under center versus the shotgun are minimal. There has been a more concerted effort to run plays from under center, but that shift was even more pronounced late last year after Gardner took the helm of the offense.

If anything's changed this year from last year in terms of blocking it's that Denard isn't around to bail it out. Borges trying to use him to cover his ass by claiming he somehow couldn't run the schemes he wanted to be cause the guy running behind them was also the one taking the snap is a weak excuse that throws Denard (of all people!) under the bus.

[After THE JUMP: WHY WOULD YOU THINK THAT MAKES ME FEEL BETTER]

26