Purdue had an interesting approach to Michigan's running game. Rather than throw bodies at the problem like Illinois, or throw bodies at the problem and get their asses handed to them for the second year in a row except this time at home like Ohio State, Purdue decided to take a mixed approach: add an extra hitter, but try to disguise where he was going to be.

Here's the part you may have noticed: Often before the snap, the Purdue DTs were quickly shifting their fronts. One of the purposes of this was to try to draw a false start (they didn't). But there was more to it than that. The Boilers were trying to disguise their attacks so Michigan wouldn't be able to pick out oddities before the snap and adjust their schemes to take advantage of them. Let me show you.

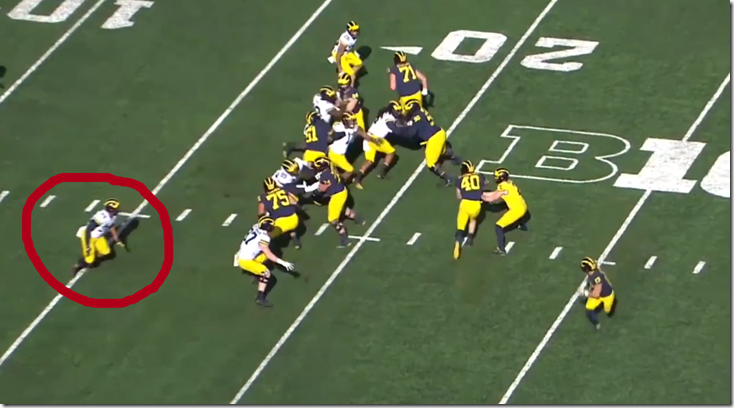

This is a run in the 2nd Quarter that got stuffed because Michigan set up for one blocking scheme and then didn't adjust on the fly when Purdue shifted the line late.

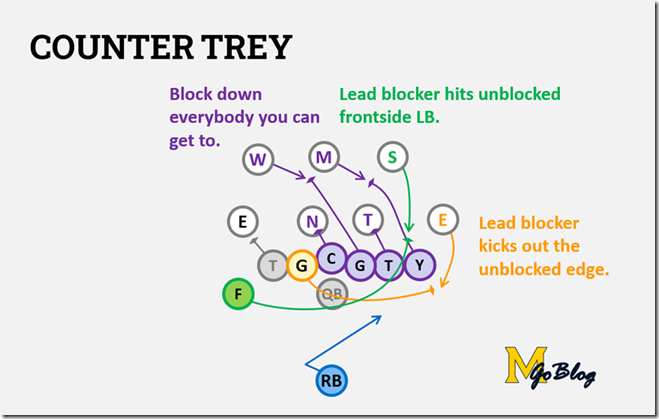

Power runs are brutal to observe on film so we'll go to my standardized color scheme:

- Purple: Blockdowns.

- Orange: Kickout.

- Green: Lead blocker.

- Blue: Running back, free hitter(s).

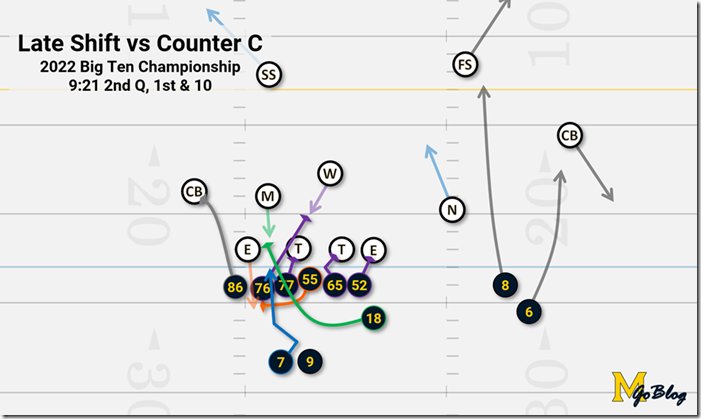

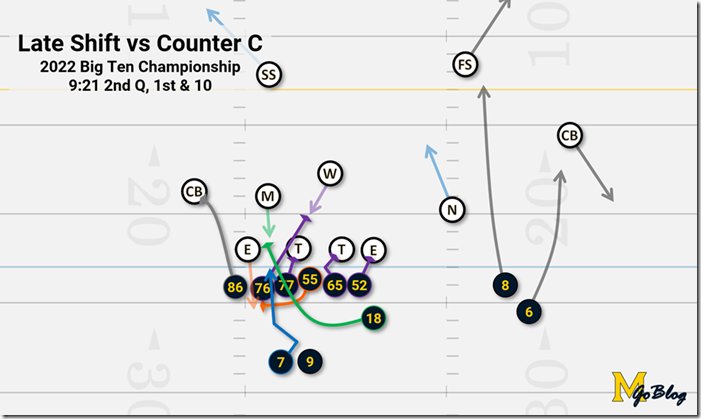

Here's what Michigan thinks they're getting before the shift.

Zooming in on the point of attack, Michigan wants to block down to the WLB, sealing both DTs with their guards, while kicking out the edge with their center and swinging Loveland around as a lead blocker. The hope with Counter is always that the defense will see your running back start moving to the opposite side and start shifting that way, creating a wider gap to run through.

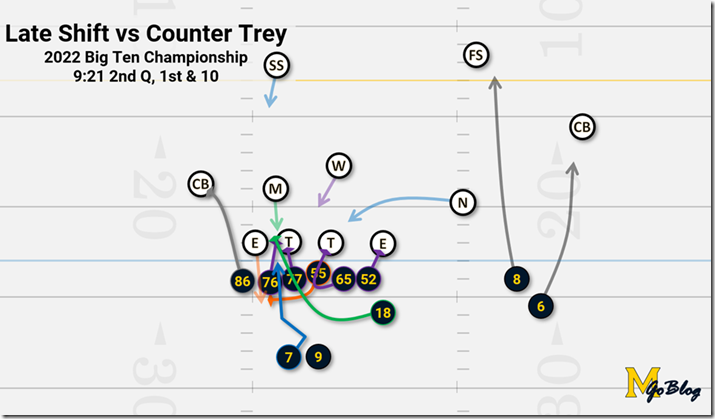

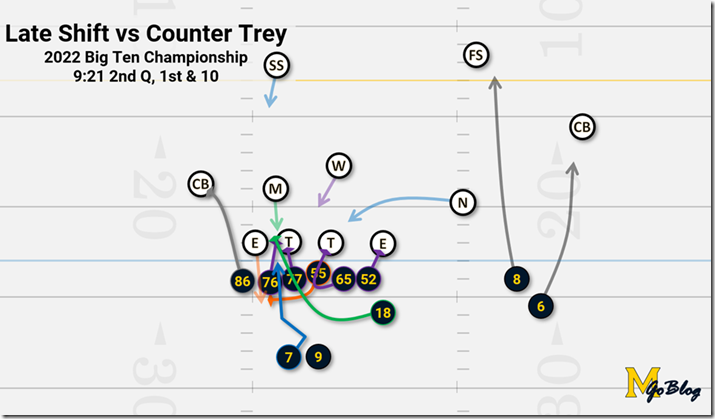

Even before the snap however, Purdue does the opposite. Here's what Michigan really gets:

The only difference is the DTs moved over. Don't bother trying to parse out where everybody's going. Just look at the mess they've made of the point of attack. How're we supposed to run through that?

[After the JUMP: Another angle]

14