caris levert point guard possibility

Previously: Part One

After looking at Michigan's stellar pick-and-roll production and how they do it last week, I dove deeper into Synergy's database to try to put this year's team in a historical context. At first I was just looking at other lead ballhandlers, then I was putting tables for every season together, then I realized I needed to add the screeners to the equation and look at how each team varied their P&R attack to do this right.

So what was going to be the second half of this series is now the second of either three or four parts. I'm trying not to make these too long to digest. These posts are going to be heavy on Synergy's stats, so I want to make a few notes before going any further.

While Synergy uses the terminology "points per possession" to describe how they measure production, that's very misleading when you're used to looking at KenPom. I'm switching over to describing Synergy stats as "points per play." The distinction is described in this useful Cleaning The Glass post:

CTG distinguishes between possessions and plays, and this distinction is important when diving into context information. A possession starts when a team gets the ball and ends when they lose it. A play ends when the team attempts a shot, goes to the foul line, or turns the ball over. If a team gets an offensive rebound, that results in a continuation of a possession but a new play. So a possession can have multiple plays.

Play contexts are per-play, not per-possession. For example, a team might come down in transition and miss a shot, get the offensive rebound, kick it out, and run a halfcourt set. Then might miss that shot but get a tip in to score and end the possession. That was all one possession, but three different plays and three different contexts: the first shot was in transition, the second in the halfcourt, and the third was a putback.

Because offensive rebounds start a new "play" within a possession, points per play are inherently going to be lower than points per possession. To help contextualize, I've included each player's national percentile rank for that season along with their stats.

For ballhandlers, "own offense" includes plays that finish with a field goal attempt, shooting foul, or turnover. "Passes" measure the result of shots that come as a direct result of the ballhandler's pass out of the pick-and-roll. "Keep percentage" is a stat I added myself that simply measures the percentage of a time the ballhandler uses his own offense instead of recording a passing play—Michigan has had players arrive at similar efficiency despite sporting very different styles.

an enjoyable pick-and-pop example

For screeners, you mostly just need to know the difference between popping, rolling, and slipping a screen:

- Popping: setting the screen and then stepping out (usually to the three-point line) for what's almost always a spot-up shot. Occasionally a more versatile big man will drive off a pop. Think Moe Wagner.

- Rolling: setting the screen and then going to the basket in the hopes of getting a layup/dunk. Think Jordan Morgan.

- Slipping: faking the screen before running to a predesignated spot—usually the rim, sometimes spotting up if it's a Wagner-type or perimeter player—as a changeup to keep defenses from overplaying the ballhandler.

As a general rule, points per play are going to higher when the screener finishes the play than the ballhander because of the nature of the pick-and-roll. A pass is usually going to be thrown to an open man when the play works; while the ballhandler could take a shot because he got open himself, he also usually has to finish the play if it's well defended.

Consider the degree of difficulty of Zavier Simpson's or Cassius Winston's shots; it's hard to be a really efficient scorer off the pick-and-roll. Morgan, while a great roll man, often just had to catch the ball and finish an uncontested shot at the rim. Most of Wagner's pick-and-pop threes went up without a real shot contest. This makes sense: there's little reason to pass the ball to your big man if he isn't open. Teams also often default to a quick screen in late clock situations, which tends to create more difficult shots the ballhandler has little choice but to take.

The other thing to note in the screener stats: under number of plays in each category, "%" shows the percentage of the time each player popped, rolled, or slipped out of their overall screener plays used. The "%ile" under points points play in each category, however, measures percentile national rank. I realize this is a little confusing but I couldn't come up with a better way than Synergy in this case.

With that out of the way, let's dive in.

[Hit THE JUMP for a year-by-year history of Michigan's pick-and-roll offense and what we can learn from it.]

Previously: Gardening Lessons (The Story), Point Guards, Preview Podcast

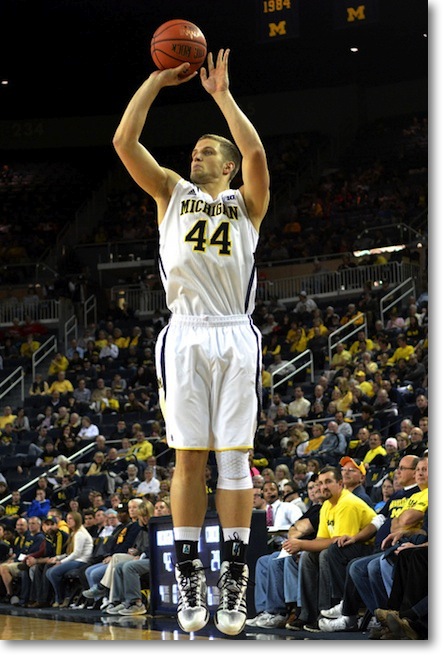

[Bryan Fuller/MGoBlog]

Let's get this out of the way: Michigan loses Nik Stauskas, and it's never good to lose a Nik Stauskas. Players that brutally efficient who can also shoulder such a large workload don't come around often; ditto shooters of that caliber. If you're expecting someone to step up and be Nik Stauskas, you will almost assuredly be disappointed.

If you're simply looking for excellent play out of Michigan's starting two and three, however, you should be quite happy this season. Caris LeVert has progressed in a scant two years from beyond-skinny-kid-who's-redshirting to beyond-skinny-kid-who's-too-good-to-redshirt to less-skinny-but-still-very-skinny-#2-scorer to, now, 200-pound-NBA-lottery-prospect. Zak Irvin entered last season as a top-30 prospect and showed absolutely no fear as an unabashed gunner off the bench; even if he doesn't diversify his game as a sophomore, which would surprise, he'll be a critical part of the offense.

LeVert will be the top option this season, and his ability to create off the dribble will be even more crucial with Stauskas in the NBA. Irvin steps into a starting role, and his shooting will be even more crucial with Stauskas in the NBA. While no one man can replace Stauskas, a reasonable step forward from each of these two can go a long way towards doing so.

[Hit THE JUMP for detailed breakdowns of each player.]

U-M can get by with three options at center (all photos by Bryan Fuller/MGoBlog)

As we welcome in the new year, we've moved on from fretting about the 2013 football team to ... fretting about the 2013-14 basketball team. There's good reason for this, of course, with Mitch McGary's season almost certainly over due to his upcoming back surgery. Your hoops mailbag questions reflect this, as all but one are related to the impact of McGary's absence in one way or another. Without further ado, here's a very McGary-centric mailbag.

@AceAnbender Where to Mitch's minutes go percentage-wise between Irvin, Morgan, and Horford?

— Bry Mac (@Bry_Mac) December 31, 2013

John Beilein announced this week that—at least for now—he's sticking with Jordan Morgan as the starting center and Jon Horford coming off the bench. I don't think McGary's absence will affect the minutes of Zak Irvin very much, if at all; he might see an increase in minutes, but that will be due to his in-season progression as opposed to any need for him to play the four, as Max Bielfeldt and Glenn Robinson III can pick up much of the slack there.

As for how the minutes will be distributed, we already have an idea thanks to the four games McGary has missed so far this season. In the first two games of the year, Horford started and played 22-24 minutes while Morgan added 12-15, with Bielfeldt getting 4-6 minutes of mostly garbage time. The split between Horford and Morgan has reversed in the last two games; Morgan played 22 and 24 minutes against Stanford and Holy Cross, respectively. While Horford only played six minutes against the Cardinal, that's because he picked up five fouls in that span, opening up a few more minutes for Bielfeldt to see the floor.

For the time being, I expect Beilein to go with a 25/15 split between Morgan and Horford, with Bielfeldt picking up a few minutes here and there at both the four and the five. The wild card here is foul trouble: Horford currently averages 4.7 fouls per 40 minutes, while Morgan is at a whopping 6.6 (the change in charge calls has really hurt him defensively). Bielfeldt got 12 minutes against Stanford. Notably, freshman big Mark Donnal didn't see any time despite all three bigs being in foul trouble in that game, which brings me to the next question...

@AceAnbender also, any chance of burning Donnal's redshirt due to need for bigs?

— Morris Fabbri (@MoMoneyMoFabbri) December 31, 2013

I don't think this is going to happen unless another big man misses extended time. Donnal is a lean stretch four at 6'9", 230 pounds, and unlike Caris LeVert last year there isn't a mountain of practice hype to suggest he'll force his way onto the court despite the need to add bulk. Between Morgan, Horford, Bielfeldt, GRIII, and Irvin, the Wolverines have plenty of options when it comes to filling minutes at the four and the five; I don't see the benefit of burning Donnal's redshirt just so he can fill in for a few minutes from time to time.

@AceAnbender i understand how important mcgary was last year but beileins offense doesnt need a big guy so why is it a big deal? #mgomailbag

— Kyle Rosenbaum (@Gkm13) December 31, 2013

This entirely ignores the best aspect of McGary's game: his ability to induce chaos. Despite playing through injury this year, he's currently ranked 29th nationally in steal rate, which not only foils opponent possessions but usually gets Michigan into the fast break, where they're much more effective than in their halfcourt offense. Neither Horford nor Morgan provides that threat, and while Horford has proven to be as good—if not better—at blocking shots than McGary, Morgan is a relative non-factor in that regard.

He's also a superlative offensive rebounder, ranking 83rd in that regard, though Horford and Morgan actually have slightly higher rebound rates on that end—we'll see if that holds with increased minutes. On the other end, while Horford is just about equal with McGary when it comes to defensive rebounding, there's a big dropoff to Morgan, who's posted just a 15.9 DReb% in comparison to 25.4% for McGary and 24.6% for Horford.

Also, McGary has easily the best chemistry with Michigan's perimeter players on the pick and roll, especially Nik Stauskas and Spike Albrecht. Horford is inconsistent when it comes to setting a good screen, while Morgan—as we've seen for four years—has trouble catching entry passes cleanly and finishing strong at the rim. McGary's passing acumen—especially when Michigan faces zone defenses—will also be missed; his assist rate is around double those of the other two bigs. Beilein's offense may not run through the post; that doesn't mean it won't suffer without McGary.

@AceAnbender odds Mitch comes back next year? Doing so could boost his draft stock, but he might feel urgency to get paid.

— Dan Roehrig (@DanRareEgg) December 31, 2013

This is going to be a very tough call for McGary; he turns 22 in June, old for a rising junior, and if he was guaranteed a first-round spot I don't think there's any question he'd turn pro. That's in seroius doubt at this point, however. Even before the injury, ESPN's Chad Ford had dropped McGary down to the #24 spot on his big board ($). In the immediate aftermath of the injury, ESPN's Jeff Goodman got this quote from an NBA general manager:

"He should have left," one NBA general manager told ESPN.com. "Now he's a borderline first-rounder. He would have been a lock last season."

The latest NBADraftNet mock has McGary going as the seventh pick of the second round. Barring a pretty miraculous recovery, McGary isn't going to have a chance to raise his stock before it's time to declare for the draft, and I believe he'll come back if he's projected as a second-round pick—unlike first-rounders, those players don't get guaranteed contracts, and a strong junior season from McGary could easily vault him back into the first round.

Alright, let's do one non-McGary question since this is getting rather depressing.

Fuller

@AceAnbender Will Caris get any real burn at PG? Seems like it could at least be a 15 min/gm change of pace lineup. #MGoMailbag

— Gustavo Adventure (@colintj) December 31, 2013

It's certainly a viable lineup, especially on the defensive end, as LeVert is currently the best player on the team at defending opposing point guards, in my opinion (with a freshman and a 5'10" guy as his competition, I don't think I'm going out on a limb here). Beilein has talked about going to this lineup more often as a situational defensive lineup at the end of games and I'm in full support of this.

15 minutes a game of this, however, might be a bit much. While LeVert is great at taking care of the ball, his assist rate (14.8%) is well below Derrick Walton's (19.5%), way below Spike Albrecht's (27.7%), and even trailing Nik Stauskas (18.0%). When LeVert is running the offense, it often devolves into him dribbling the air out of the ball in isolation situations; while he's getting pretty good at getting buckets out of those plays, that's not a very sustainable way to run an offense.

That said, Beilein's offense doesn't really require a traditional point guard, and between Stauskas and LeVert there are two solid creators off the dribble when Michigan goes big. If they can get the offense to run more smoothly when LeVert initiates the play, this lineup could very well turn into Michigan's best—that's a big if, though, and deemphasizing the point guards could hamper Walton's development.

2