blocking

This is a decennial series covering Michigan's last ten years that were. We could have made an all-2010s team and published it when everyone else did, but how MGoBlog would that be? This time we're doing this as a staff since one guy could forget. Previously: The aughts: ESPN Images, Michigan's offense, Michigan's defense, Worst Plays of The Decade Part 1, Worst Plays Part 2, Best Plays Part I, Best Plays Part II.

We figured the best way to lead off Of the Decade 2020 is with the guys carving out a path. Ten is a nice round number so we'll go with top ten blocks thrown from 2010-2019. These are ranked by gut because the only number you can put on something like this is on the UFR scale. Points are arbitrarily awarded for:

- Defenders removed

- Meanness of block(s)

- General Splattitude

- Significance of moment

- Deservedness of recipient

Let us ruminate.

--------------------------------------

10. EATING OUT

Dealer: Vincent Smith

Recipient: Troy Stoudermire

Scene of the Crime: First drive of 2012 Minnesota

We'll start with a shorty. Friend of the blog Vincent Smith was the best pass-blocking back at Michigan since Hart, and if we wanted to, this whole article could be #2 flipping blitzers. But then there was the time he got to split out wide and face a Minnesota cornerback. This is a thing spread teams do all the time to unbalance a defense and reveal their coverage, and usually means the back's job is done for the play.

Obviously Vincent was told his job is to bury the corner to clear space for a quick out to Kwiatkowski He very much obliged:

CLONK-O-METER:

- Defenders removed: 1

- Impact: 0/5. There was no throw because—ah 2012—Mealer and Barnum screwed up a stunt, and had there been one it was going to be PI.

- Meanness: 4/5. That's a cornerback man.

- Splattitude: 3/5. I'm sure he remembers this. Probably felt it all game.

- Karma: 0/5. Stoudermire holds the Big Ten record for kickoff return yardage, which he achieved before he was granted a 6th year. He was the only Big Ten-caliber player in the Gophers' back seven, had an injury history, was one of my many inspired late Draftageddon picks, and seems to be a good dude. Planting him like that was a dick move. (Not sorry)

[After THE JUMP: Pads recommended.]

I found this incredibly annoying this weekend:

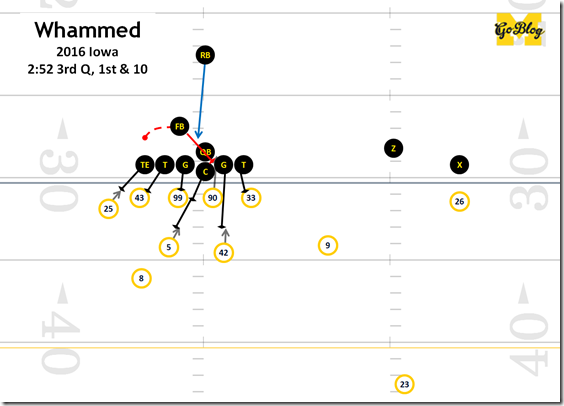

Michigan has 8 1/2 in the box, and yet Iowa is able to get 8 yards on 1st down. Even more galling is they did it with a nifty trick that hadn’t been seen much of in the Big Ten until Harbaugh brought it back last year. It’s the wham. And it had no right to go this well.

Wham Defined

A wham is a first level block by the fullback or TE, freeing up an offensive lineman to release to the next level. It’s a type of Trap, which is a when you leave an interior defensive lineman unblocked before hitting him from another angle. But when you think of a “trap” it’s usually pulling an offensive lineman to blindside the DL you left unblocked to roar into the backfield.

A wham is less about catching the defense overreacting and more about winning a one-on-one matchup they didn’t expect, in this case between a fullback or H-back and an interior DL. The block is a kick-down, and happens within a second of the snap. If executed, you’ve erased the defense’s most important run defender with your fullback’s block, and your center (who’s often your best run blocker) gets a free release into the linebackers.

Wham block in red

Often a wham block starts with that fullback or tight end in motion. This keeps him out of view of the DT he’ll end up blocking until it’s almost too late, and can give him more of a head start, since the fullback is bound to be giving up some weight on the DT, and will have to make up for it with momentum.

BlueGraySky put together a great video compilation of Notre Dame’s wham blocks from a decade ago:

If you’re mad about watching Domers, know that Michigan’s ‘06 defense appears twice and does a pretty good job against it.

[After the JUMP: What they win, what they risk, and how it goes]

You have read somewhere that power offenses like Michigan are often dependent on winning big, strong, man-a-mano battles. While that's quite an oversimplification, it's also a truth. Run defenders are usually given pretty simple assignments like "defend this gap at all costs!" or "don't let anyone outside you and hit anyone who tries" so confusing them into leaving your lane open is not sustainable. Sometimes you just need to shove the dude out of the way to make a gap. Sometimes you gotta…

[MC5 lyric you know is coming is not safe for work]

There's plenty going on in that play, but we're going to focus on two opposing concepts that are in play on just about every running play:

FORCE PLAYER

Fritz Shurmer:

"The defender who is responsible for tackling or making sure the ballcarrier does not get outside of him. It is his responsibility either to tackle the ballcarrier or to force him to cut back into the pursuit pattern."

I took that quote from a coachoover post post worth reading. The force defender is being pulled in two directions. He MUST set up far enough outside that he won't get edged, but he's also got to be far enough inside to keep the gap small. Typically you put a little money in the bank; if the ballcarrier tries to go outside of you he's going to either run right into you or the sideline. The sideline is helpful but also passive. Better to redirect the ballcarrier to your friends.

That said, the force defender can't be too conservative. Goal A is set the edge, but every step towards the edge is a lane that's one step wider. The force defender sets up at a 45 degree angle, able to attack upfield or across it. That setup also gives him leverage to not get blown back by a…

KICKOUT BLOCK

Football Outsiders:

Kickout block – On a running play, this blocker is running parallel to the line of scrimmage and his job is to to keep the outside edge rusher (usually a DE or OLB*) from crashing to the inside. It's almost always a fullback or a pulling guard who does the kickout block. Opposite of a crackback block.

* [or, like in the video above, a Cover 2 cornerback.]

If a force player has done his job well, there isn't much space between the force player's area of effect and the defensive pursuit. A kickout block attacks the force defender, thwacking him toward the sideline, preventing him from a tackle attempt, and creating a running lane over the resulting viscera. That's why FO says it's almost always an offensive lineman or fullback.

A kickout block is going to go as well as physics allow: the more accelerated mass you can hit him with, the more room there is to run.

[Hit THE JUMP to see it in action]

52