basketball wonkery

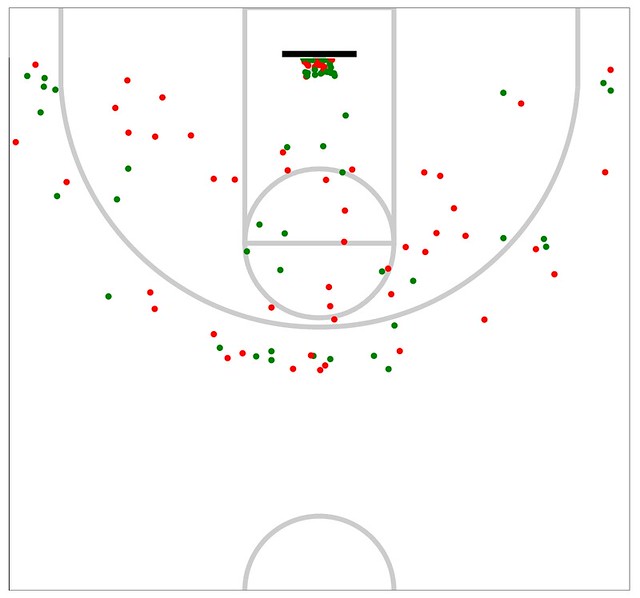

You may have noticed, especially during the second half of Monday's thumping of Bucknell, that Michigan's offense has looked a little different this season. This season's shot chart, via Shot Analytics, puts it in picture form (green dots are makes, red misses):

A little over 34% of Michigan's shots this season have come from midrange, compared to just over 25% last season. It's not a good change, either; midrange jumpers are by nature the game's most inefficient, and the Wolverines are hitting just 33% of such shots this season, down from 39% in 2013-14. A higher volume and lower efficiency is obviously not a good thing.

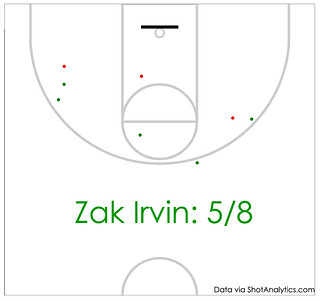

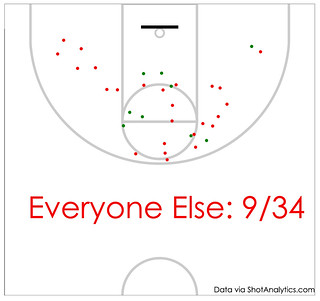

A closer look reveals that there may be something here worth sticking with, however. With the usual sample size caveats applying, here's a simple breakdown of what's working and what's not:

(If you're wondering why it looks like a three is included in Irvin's chart, he had a foot on the line.)

Simply put, Zak Irvin is working, and a look at the tape reveals that this may be no fluke, especially since Irvin wasn't bad on midrange elbow jumpers last season (8/19). Here are all of Irvin's midrange attempts from this season:

He's getting these shots primarily in two ways: catch-and-shoot jumpers (3/3) and step-ins when defenders overplay his outside shot (2/4). The aborted drive to the rim off a curl-cut stands as the exception, not the rule.

[Hit THE JUMP for a look at why the rest of the team isn't shooting like Irvin, as well as a picture pages of how M is getting Irvin good midrange looks.]

In today's basketball world, the corner three is superior in value to any shot that doesn't come at the rim. It's also the toughest shot in the game to create for yourself; to do so requires a silky touch, a tapdancer's precision, and the guts and/or stupidity to launch a shot that would earn most players a quick trip to the bench.

Grantland's Kirk Goldsberry covered this topic in exacting detail yesterday, posting this fascinating chart that shows the assist rate for shots made from each spot on the floor—three-pointers usually require assistance, and the rate increases as the shooter gets closer to the baseline [click to embiggen]:

Goldsberry's post focused on the players who could create those high-percentage shots for their teammates, because even in the NBA, finding players who do it themselves is a difficult proposition:

Meanwhile, unassisted corners 3s are the white buffalos of perimeter shooting. They don’t come around too often. As it turns out, dribbling into the corner and firing up a 3 is very difficult, and perhaps unwise, as well. It takes a special kind of player to even attempt this task, as Rudy Gay demonstrates for us here: [GIF of Rudy Gay dribbling into the corner and badly airballing a fallaway attempt]

Which brings me to Nik Stauskas. I've written before about his pregame shootaround routine, but it's worth mentioning again. In addition to practicing the usual spot-up threes from various points around the arc, Stauskas always spent time in the corner working his crossover stepback, a move designed to clear out just enough space to launch from a spot that opponents long ago learned to keep him from at all costs.

Without ever having to look, Stauskas's feet nestled precisely between the three-point line and the sideline, the product of countless practice hours transforming process into instinct. By the end of his Michigan career, he made these audacious warmup attempts at about the same outrageous clip that he hit his normal shots. Michigan's shootarounds were considered must-watch because of the team's—and especially Glenn Robinson's—impromptu dunk exhibitions; for me, however, the Stauskas Stepback was always the highlight.

[Hit THE JUMP for more on Stauskas's incredible shot creation in GIF, still, and chart form. Oh, and some more words, too.]

Too many of these (Bryan Fuller/MGoBlog)

There's no question Glenn Robinson III is off to a rough start in his sophomore season. Tasked with creating more offense in the absence of Trey Burke and Tim Hardaway Jr., he's struggled to do so, and his efficiency has plunged—he's shooting 44% from the field after hitting 57% of his shots last year. In Michigan's three losses, representing three of the four toughest teams they've played, he's all but disappeared, and only one of those (Charlotte, against which he played nine minutes before exiting the game after falling on his back) can be explained away by mitigating circumstances.

In a highly recommended stat-based look at Michigan's offensive issues so far this year, UMHoops cited a major reason for GRIII's regression—his lack of attempts at the rim [emphasis mine]:

Last year Robinson attempted 43.5% of his field goals at the rim and converted at a 78% rate. You remember those plays: Trey Burke penetrates and finds Robinson creeping along the baseline for an alley-oop or Robinson leaks out for an easy dunk in transition. Robinson was among the best finishers in the country a year and was the 10th most efficient offensive player in the country because of it.

This year, just 21.4% of Robinson’s field goal attempts have come at the rim. He’s finishing at an improved 88.9% rate but the opportunities aren’t nearly as plentiful. That’s a major problem because that’s what Robinson does best.

Above all else, this is the clear issue with Robinson this year; without Burke—and to a lesser extent, Hardaway—commanding the full attention of opposing defenses, the easy looks that were there last year aren't happening this year, and Robinson's attempts to create his own offense haven't been nearly as effective.

In an effort to expand on this, I went back to the Iowa State game film—the only game in which Michigan faced a quality opponent, GRIII played extensively and commanded at least 15% of the team's possessions, and the opposing defense wasn't face-guarding Nik Stauskas—to see how his shots were created. This is every shot attempt and turnover by Robinson before Michigan was down multiple possessions in the final two minutes; you should see a common thread:

Most of Robinson's attempts are happening in transition, obviously. When Michigan was in their halfcourt offense, he was almost entirely a non-factor. A few more observations from the tape above and this season as a whole after THE JUMP.

[JUMP for stat wonkery, what's not working, and reasons for hope.]

16